Joan of Arc

Chapter 5

IMPRISONMENT AND TRIAL

The news of Joan's capture soon reached Paris, and within a few hours

of that event becoming known, the Vicar-General of the Order of the

Inquisition sent a letter to the Duke of Burgundy, accompanied by

another from the University of Paris, praying that Joan of Arc might

be delivered up to the keeping of Mother Church as a sorceress and

idolatress. That terrible engine, the Inquisition, had, like some

mighty reptile scenting its prey near, slowly unfolded its coils.

Whether Bedford had or had not caused these letters to be sent the

Duke is not known, but the Regent had both in the Church and the

University of Paris the men he wanted—instruments by whom his

vengeance could be worked on Joan of Arc; and he had the astuteness to

see that in calling in the aid of the Church, and treating Joan of Arc

as a heretic and witch, the rules of war could be laid aside. What no

civilised body of men could do, namely, kill a prisoner of war, that

thing could be done in the name and by the authority of the Church and

its holy office; and in the Bishop of Beauvais, the inexorable

Cauchon, Bedford had the tool necessary to his hand whereby this

dastardly plot could be carried out.

The first move that Bedford now was obliged to take was to secure the

victim; and in order to do so the Bishop of Beauvais was applied to.

The name of Peter Cauchon, Bishop of Beauvais, will go down to the

latest posterity with the execration of humanity, for the part he

played in the tragedy of the worst of judicial murders of which any

record exists. Let us give even the devil his due. According to

Michelet the Bishop was 'not a man without merit,' although the

historian does not say in what Cauchon's merit consisted. Born at

Rheims, he had been considered a learned priest when at the University

of Paris; but he had the reputation of being a harsh and vindictive

opponent to all who disagreed with his views, within or without the

Church. He was forced to leave Paris, in 1413, for some misconduct. It

was then that Cauchon became a strong partisan of the Duke of

Burgundy. It was through the Duke that he obtained the See of

Beauvais. The English also favoured Cauchon, and obtained for him a

high post in the University of Paris. When the tide of French success

reached Beauvais, in 1429, Cauchon was obliged to escape, and found

shelter in England. There Winchester received him with cordiality.

While in England, Cauchon became a thorough partisan of the English,

and the humble servant of the proud Prince-Cardinal. Winchester

promised Cauchon preferment, and, when the See of Rouen fell vacant,

recommended the Pope to place Cauchon on its throne. The Pope,

however, refused his consent, and the Rouen Chapters would hear naught

of the Anglicised Bishop. At that time the Church at Rouen was at war

with the University of Paris, and did not wish one of the members of

that University placed over it.

Joan of Arc's place of capture happened to be in the diocese of

Beauvais, and although Cauchon was now only nominally Bishop of

Beauvais, he still retained that title. Cauchon now placed himself,

body and soul, at the disposal of the English, hoping thereby sooner

to obtain the long-coveted Archbishopric of Rouen in exchange for

helping his friends to the utmost in his power by furthering their

schemes and in ridding them of their prisoner once and for ever. The

bait held out by Winchester and Bedford was the Archbishopric of

Rouen, and eagerly did Cauchon seize his prey. What added to his zeal

was his wish to gratify base feelings of revenge on those who had

thrust him out of his Bishopric of Beauvais, and on her without whose

deeds he might have still been living in security in his palatial home

there.

After a consultation with the leaders of the University of Paris,

Cauchon arrived at the Burgundian camp before Compiègne on the 14th

of July, and claimed Joan of Arc as prisoner from the keeping of the

Duke of Burgundy. Cauchon justified his demand by letters which he had

obtained from the doctors of the University, and he made the offer in

the name of the child-king of England. The sum handed over for the

purchase of the prisoner was 10,000 livres tournois, equivalent to

61,125 francs of French money of to-day—about £2400 sterling. This

was the ordinary price in that day for the ransom of any prisoner of

high rank. Luxembourg, to his shame and that of his order, consented

to the sale on those terms, and Cauchon soon returned with the news of

his bargain to his English employers.

The whole transaction sounds more like what one might expect to have

occurred amongst an uncivilised nation rather than among a people who

prided themselves on their chivalry and their usages of fair-play in

matters relating to warfare. That a high dignitary of the Church, and

a countryman of Joan of Arc, should have bought her from a prince, the

descendant of emperors and kings, also a countryman of the heroic

Maid's, for English gold, is bad enough; and that the so-called 'good'

Duke of Burgundy should have been a silent spectator of the infamous

transaction, brands all the actors as among the most sordid and

meanest of individuals. But what is infinitely worse is the fact that

no steps appear to have been taken by Charles to rescue the Maid, or

to attempt an exchange of her for any other prisoner or prisoners.

Thus Joan of Arc, bound literally hand and foot, was led like a lamb

to the shambles, not a hand being raised by those for whom she had

done such great and noble deeds.

The University of Paris, whose decisions carried so great a weight in

the issue of the trial of the Maid of Orleans, consisted at this

period of an ecclesiastical body of doctors; but as far as its

attributes consisted it was a body secular, and holding an independent

position owing to its many privileges. The University was a political

as well as an ecclesiastical body, supreme under the Pope above the

whole of the Gallican Church. Although divided into two parties

through the war then raging between England and France, its judicature

was greatly influenced by the Church. It was a matter of certainty

that the Doctors of Theology who sat in the University of Paris, and

who were all, or nearly all, French by birth, would favour the

English, and give an adverse decision to that of those French

ecclesiastics who had examined into Joan's life and character when

assembled at Poitiers, and who then considered her to be acting under

the influence and with the protection of the Almighty.

As a prisoner, Joan of Arc's behaviour was as modest and courageous as

it had been in her days of success and liberty. In the first times of

her durance, d'Aulon, who, as we mentioned, had been captured at the

same time, appears to have been allowed to remain with her. On his

telling her that he feared Compiègne would now probably be taken by

the enemy, Joan of Arc said such a thing could not occur, 'For all the

places,' she added, 'which the King of Heaven has placed in the

keeping of King Charles by my means will never again be retaken by his

enemies, at any rate as long as he cares to keep them.'

Although willing to endure for the sake of her beloved country all the

cruelty her enemies could inflict upon her, Joan was most anxious to

return in order to continue her mission. While in the castle of

Beaulieu she made a desperate attempt to escape. She managed to

squeeze herself between two beams of wood placed across an opening in

her prison, and was on the point of leaving her dungeon tower when one

of the jailers caught sight of her, and she was retaken. Probably in

consequence of this attempt, Joan of Arc, after an imprisonment of

four months at Beaulieu, was transferred thence by Ligny to his castle

of Beaurevoir, near the town of Cambrai, a place far removed from the

neighbourhood of the war, and consequently more secure than Beaulieu.

At Beaurevoir lived the wife and the aunt of Ligny; they showed some

attention and compassion to the prisoner. They offered her some of

their dresses, and tried to persuade her to quit her male attire.

Joan, however, refused: she gave as her reason for not complying with

their request that the time had not yet arrived for her to cease

wearing the clothes she had worn during the time of her mission. That

she had good reason not to don woman's attire even when at Beaurevoir,

and keep to her male attire as a protection, is probable, as she was

not safe from wanton insult at the hands of the rough soldiery placed

about her person. This clinging to her male dress, we shall see, under

similar circumstances at Rouen, was the principal indictment made

against her by her executioners.

At Beaurevoir Joan of Arc was placed in a chamber at the top of a high

tower, whence Ligny thought that no attempt at escape would be made,

but Joan of Arc tried once again to recover her liberty. In the course

of her trial she told her judges how her voices counselled her not

again to make this venture, and of her perplexity whether she should

obey them, or, at the risk of her life, escape from the clutches of

the English, for at this time she knew that she had been sold to her

bitterest foes.

What appears to have determined her decision was hearing that

Compiègne was in imminent peril of falling into the hands of the

English, and that the inhabitants would be massacred. In her

desperation, feeling, like young Arthur, that

'The wall is high; and yet will I leap down:—

Good ground, be pitiful, and hurt me not!...

As good to die, and go, as die, and stay'

she knotted some thongs together and let herself out of a window; but

the thongs broke, and she fell from a great height—the tower is

supposed to have been no less than sixty feet high. She was found

unconscious at its foot, and for several days she was not expected to

recover from the injuries she had received. But she was doomed for a

far more terrible death.

For several days Joan of Arc took no nourishment. Gradually she

revived, and she told her jailers that her beloved Saint Catherine had

visited and comforted her; and she also told them that she knew

Compiègne would not be taken, and would be free from its enemies

before the Feast of Saint Martin.

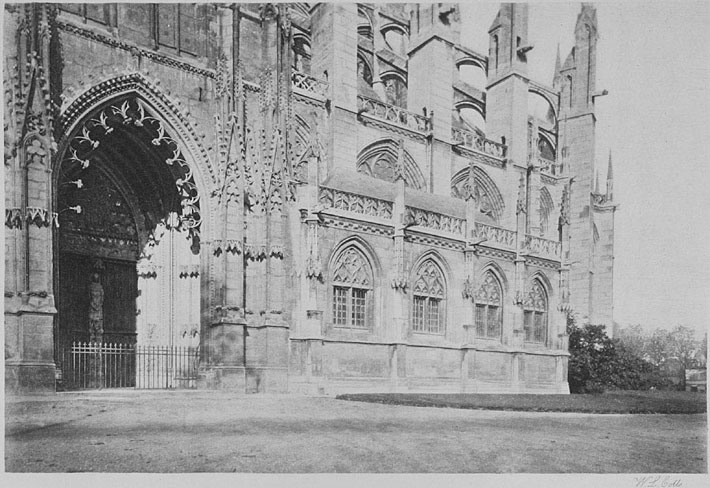

Beaurevoir is now a ruin: although above the lintel can still be seen

the coat-of-arms of the jailer of the Maid, the tower in which she was

imprisoned, and from which she so nearly met her death, has been

destroyed.

In the month of November of that year (1430), in spite of the

entreaties of his wife and aunt, Ligny delivered up his prisoner into

the custody of the Duke of Burgundy, from whose keeping she was soon

transferred into that of the English.

On the 20th of November the University of Paris sent a message to

Cauchon, advising him to bring Joan of Arc before a tribunal. Cauchon,

however, waited the arrival of Winchester, bringing with him his

great-nephew, Henry VI. Winchester arrived with the boy-king on the

2nd of December. The Cardinal intended the function of the crowning of

his great-nephew to be as imposing a ceremony as possible; and he

also meant, by defaming the source of the French King's successes, to

show the French people that Charles' coronation at Rheims had been

brought about by what the Regent Bedford called a 'limb of the evil

one.' It was, therefore, Bedford's plan that it should be declared

before the world that Joan of Arc was inspired by Satanic agencies,

and that consequently the French King's coronation was also due to

these agencies. By similar means it would be made clear that all the

French victories were owing to the same influence; for were it not,

argued the English, they would be proved to have been themselves

fighting against and defeated by—not the spirit of evil but—the

spirit of righteousness.

Nothing, indeed, could be clearer than Winchester's argument. It was

now only necessary that Joan of Arc should be at once placed on her

trial as a sorceress and a witch—one who was in league with the evil

one; and, when that had been satisfactorily proved, that she should

publicly meet with the fate which a merciful Church had, in its

infinite wisdom, ordained for such as she. Thus would the English army

and people be avenged, and the French King's crown and prerogative

suffer an irreparable damage.

From Beaurevoir, Joan of Arc was first taken to the town of Arras,

thence to Crotoy, where, about the 21st of November, she was handed

over to the English.

A chronicler of that day writes that the English rejoiced as greatly

on that occasion as if they had received all the wealth of Lombardy.

The Duke of Burgundy had never merited the title of 'Good,' which,

somehow or other, has been linked with his name. Had he been the most

virtuous of princes of any time, he yet deserves to have his memory

branded for the part he then took in the sale of Joan of Arc—a

transaction whereof the poor excuse of not losing the benefits of his

alliance with the English avails nothing. For this, if nothing else,

we reverse the good fame which lying history has accorded him.

In the underground portion of a tower at Crotoy, still to be seen,

although the upper part has disappeared, facing the sea, is a

door-way, which local tradition points out as that of the dungeon of

Joan of Arc. Crotoy, or Le Crotoy, is on the coast of Picardy, a

little to the north of Abbeville. In the fifteenth century it was a

place of some warlike importance, especially to the English. Its

situation near the coast, and the strength of its fortress, made Le

Crotoy one of the principal places on the sea line, whence stores and

war provender could be carried into France. Le Crotoy had fallen into

possession of the English through the marriage of Henry III. with

Eleanor of Castille, Countess of Ponthieu, of which Crotoy formed a

part. During the hundred years' war, the port could receive vessels of

considerable tonnage; and from this point the booty taken by the

English could be shipped and sent across the Channel. Now but a few

vestiges can be traced of its once strong and ably fortified castle. A

few years ago, a statue, representing the Maid of Orleans in the garb

of a prisoner, was placed near the ruins of the castle in which she

passed most of the month of December, 1430.

At Crotoy, Joan of Arc was permitted to assist at the celebration of

the Mass in the chapel of the castle; and while here she received a

visit from some of her admirers from Abbeville—a few noble hearts who

still remained loyal to the once all-powerful deliveress of their

country, now a poor and abandoned prisoner on her road to a long

imprisonment and a cruel death! Touched by this mark of sympathy from

these Abbeville folk, Joan gave them, on parting from them, her

blessing, and asked them to remember her in their prayers. The

enlightened clergy and doctors, lay and spiritual, who formed the body

known as the University of Paris, preferred that Joan of Arc should be

sent to the capital, there to undergo her trial, and wrote to this

effect to Bedford, through the name of the boy-king. They also

despatched a letter to Cauchon (probably inspired by Bedford), in

which they rated him for not bringing the Maid at once to her trial.

They told him he was showing a lamentable laxness in not immediately

punishing the scandals which had been committed under his jurisdiction

against the Christian religion.

Paris was not considered enough of a safe place to take Joan of Arc

into; the French lay too near its walls, and the loyalty of its

citizens to the English was a doubtful quantity. Besides, it was not

convenient that the University of Paris should be allowed the entire

direction of the trial. It was well that the University should be made

use of; but Cauchon relied on the Inquisition to carry out his and

Bedford's plan. Cauchon must be the principal agent and judge, and he

felt, with Bedford, that they had a freer hand if the trial were to be

at Rouen; therefore Rouen was decided on as the place of trial and

punishment. Rouen, also, being in the midst of the English

possessions, was perfectly safe from attack, should it occur to any of

Joan of Arc's countrymen to attempt a rescue.

At the close of December Joan of Arc was taken across the river Somme,

in a boat, to Saint Valery, and thence, strongly guarded, and placed

on horseback, she was led along the Normandy coast by Eure and Dieppe

to the place of her martyrdom. On arriving at Rouen it was seriously

debated by some of her captors whether or not she should be at once

put to death. They suggested her being sewn into a sack and thrown

into the river! The reason these people gave for summarily disposing

of Joan of Arc without form or trial was that, as long as she lived,

there was no security for the English in France. As has already been

noticed, those who commanded and sided with the English were desirous

that Joan of Arc should be first branded as a witch and a sorceress,

both by the doctors of the Church and by the State, before being put

to death.

Arrived at Rouen, Joan of Arc was immured in the old fortress built by

Philip Augustus. One tower alone remains of the seven massive round

towers which surrounded the circular castle. Her jailers had the

barbarity to place their prisoner in an iron cage, in which she was

fastened with iron rings and chains, one at the neck, another at the

hands, and a third confining the feet. Joan was thus caged as if she

were a wild animal until her trial commenced. After that, she was

chained to a miserable truckle bed.

A chronicler of that time, named Macy, tells the following story of an

incident which, for the sake of English manhood, one trusts is untrue.

Among others who went to see Joan of Arc in her prison came one day

the Earl of Warwick, with Lord Stafford and Ligny—Joan's former

jailer. The latter told her in a jeering way that he had come to buy

her back from the English, provided she promised never again to make

war against them.

'You are mocking me,' said Joan of Arc. 'For I know that you have not

the power to do that, neither the will.' And she added, 'I know well

that these English will kill me, thinking that by doing so they will

reconquer the kingdom of France; but even if there were one hundred

thousand Godons more in France than there are now, they will never

again conquer the kingdom!'

On hearing these words Stafford drew his dagger, and would have struck

her had not Warwick prevented the cowardly act.

Cauchon formed his tribunal of the following:—

1. John Graverent, a Dominican priest, D.D., Grand Inquisitor of

France. It was he who appointed John Lemaître as judge in the trial of

the Maid. The following July this Graverent preached a sermon in

Paris, in which he glorified the death of Joan of Arc.

2. John Lemaître, who represented the Inquisition on the trial. He was

a Dominican prior. He appears to have been a feeble-minded creature,

and a mere tool of Cauchon and Graverent.

3. Martin Bellarme, D.D., another Dominican, and also a member of the

Inquisition.

4. John d'Estivet, surnamed 'Bénédicité,' canon of Beauvais and

Bayeux, was another of Cauchon's creatures. He acted the part of

Procureur-Général during the trial. D'Estivet was a gross and cruel

ecclesiastic, and it is somewhat satisfactory to know his end. He was

found dead in a muddy ditch soon after Joan of Arc's death. As M.

Fabre justly says, 'He perished in his native element.'

5. John de la Fontaine, M.A. He was Conseille d'Instruction during

the trial. In the course of it he was threatened by Cauchon for having

given some friendly advice to the prisoner, and escaped from Rouen

before the conclusion of the trial.

6, 7, 8. William Manchon, William Colles, and Nicolas Taquel, all

three recorders. They belonged to the Church. It is to Manchon that we

are indebted for a summary of the most interesting account of the

trial. We shall find that at the time of Joan's execution this man was

horrified at the part he had taken in it. He confesses his horror at

having received money for his infamy, but instead of casting his

blood-money at the feet of Cauchon, and hanging himself like another

Judas, he somewhat naïvely informs us that he laid it out in the

purchase of a breviary in order to pray for the soul of the martyr.

9. Massieu, another priest, who acted as the sheriffs officer. He

appears to have had feelings of humanity, and attended Joan to the

end.

10. Louis de Luxembourg, Bishop of Thérouenne and the Chancellor of

France to King Henry VI. This bishop was the go-between of Cauchon and

Winchester throughout the trial; but he only appears to have taken

part in these occasions during the examinations. It was he who was

made Archbishop of Rouen, which post Cauchon had hoped to gain; and it

was for this archbishopric that Cauchon had taken the presiding post

during the trial.

11. John de Mailly, Bishop of Noyon; he was another staunch auxiliary

of Cauchon. In the year 1456, at the trial for the rehabilitation of

Joan of Arc's memory, Mailly signed his name among those who condemned

the deed he had helped to carry out.

12. Zanon de Castiglione, Bishop of Lisieux. One of the reasons that

this man gave for condemning Joan of Arc to the stake was that she was

born in too low a rank of life to have been inspired by God. This

decision makes one wonder so aristocratic a prelate could demean

himself by belonging to a religion which owed its origin to One who

had followed the trade of a carpenter.

13. Philibert de Montjeu, Bishop of Coutances.

14. John de Saint Avét, Bishop of Avranches. The latter was the only

one of the above Bishops, Dominicans, and members of the French Church

who gave his vote against the condemnation of Joan of Arc, although

the trial minutes have not recorded the fact.

Besides the above French prelates, were:—

15. John Beaupère, M.A. and D.D., formerly a rector of the University

of Paris, also a canon of Besançon. It was he who, with the following

five representatives of the University of Paris, took the most

prominent part in the cross-questioning of the prisoner.

16. Thomas de Courcelles, a canon of Amiens, of Thérouenne, and of

Laon. This person was employed to read the articles of accusation to

the prisoner, and was in favour of employing torture to make Joan

confess what was required of her by her prosecutors. He was considered

one of the shining lights of the University of Paris. He died in 1469,

and until the Revolution an engraved slab, on which his virtues and

learning were recorded, covered his remains.

17. Gerard Feuillet. He was sent to Paris during the trial in order to

lay the twelve articles of accusation before the University, and did

not take part in the latter portion of the trial.

18. Nicolas Midi, D.D., a celebrated preacher. He is supposed to have

been the author of the twelve articles; and he it was who preached a

sermon at the time of the execution of Joan of Arc. Attacked soon

after by leprosy, he sufficiently recovered to see Charles VII. enter

Paris; and he had the audacity to send the King an address of

felicitation in the name of the faculties of the University by whose

instrumentality Joan of Arc had been executed.

19. Peter Morice, a doctor of the University and a canon of Rouen. He

was one of the most eager to bring Joan to the stake.

20. James de Touraine, also a doctor of the University, was violently

hostile to Joan of Arc.

The above six doctors, with Cauchon, were those who had most to do

with the proceedings of the trial, and those whose duty it was

principally to question the prisoner.

21. Nicolas Loiseleur, M.A., a canon of Rouen; he was the most abject

of all the gang of priests and doctors who formed part of this

infamous tribunal. It was Loiseleur who, in the disguise of a layman,

attempted to worm secrets from Joan, pretending to be her friend and

sympathiser. When he found he gained nothing by the subterfuge, he

resumed his clerical garb, and succeeded in getting, under the

promise of secrecy from his order, a confession from the prisoner. He

also introduced spies into the prison who took notes of Joan's words.

When the idea was mooted of putting Joan of Arc to the torture,

Loiseleur was one of the most urgent for it to be applied. However, on

the day of the execution this man, who, strange as it may seem,

appears to have had some kind of conscience, or at least to have been

able to feel remorse for the base part he had played in the trial of

the Maid, implored Joan of Arc's forgiveness. He, however, after the

execution, helped Cauchon to spread calumnies regarding their victim.

This infamous scoundrel died suddenly at Basle.

22. Raoul Roussel de Vernon, D.C.L., and the canon treasurer of the

Cathedral of Rouen. He acted throughout the trial as reporter. In 1443

Roussel became Archbishop of Rouen.

23. Robert Barbier, also a D.C.L., and canon of Rouen Cathedral.

24. Nicolas Coppequesne, also a canon of Rouen Cathedral.

25. Nicolas de Venderès, a canon of Rouen, and Cauchon's chaplain.

26. John Alessée, also a canon of Rouen. This Alessée was greatly

moved at the heroine's death, and exclaimed, 'I pray to God my soul

may one day be where hers is now.'

27. Raoul Auguy, another canon.

28. William de Baubribosc, also a canon of Rouen.

29. John Brullot, another canon and precentor of Rouen.

30. John Basset, another canon and a M.A.

31. John Brullot, another canon. Besides these were seventeen others,

named Caval, Columbel, Cormeilles, Crotoy, Duchemin, Dubesert, Garin,

Gastinel, Ledoux, Leroy, Maguerie, Manzier, Morel, Morellet, Pinchon,

Saulx, and Pasquier de Vaux, who became Bishop of Meaux, Evreux, and

Lisieux. In all, nine-and-twenty canons of Rouen.

After these came a list of mitred abbots, priors, and heads of

religious houses: Peter de Crique, Prior of Sigy; William Lebourg,

Prior of the College of Saint Lô of Rouen; Peter Migiet, Prior of

Longueville.

After these priors came eleven abbots: Durement, Abbot of Fécamp,

later Bishop of Coutances; Benel, Abbot of Courcelles; De Conti, Abbot

of Sainte Catherine; Dacier, Abbot of Saint Corneille of Compiègne;

Frique, Abbot of Bee; Jolivet, Abbot of Saint Michael's Mount in

Normandy; Labbé, Abbot of Saint George de Bocherville; Leroux, Abbot

of Jumièges; Du Masle, Abbot of Saint Ouen; Moret, Abbot of Préaux;

and Theroude, Abbot of Mortemer.

Besides these there were many doctors and assessors from the

University of Paris; among the latter lot appears the name of an

English priest, William Haiton, a secretary of Henry VI. He and

William Alnwick, Bishop of Norwich, Privy Seal to the English King,

are the only two names belonging to the English clergy who took part

in the trial. The Cardinal of Winchester never once appeared during

the proceedings, although he was, together with Cauchon, the prime

mover in the business. To complete the list of the other French

clergy—French only by birth and nationality indeed—must be added the

names of Chatillon, Archdeacon of Evreux; Erard, Canon of Langres,

Laon, and Beauvais; Martin Ladvenu, a Dominican priest, one of the few

who showed some humanity to the prisoner. It was Ladvenu who heard her

confession on the day of her execution, and who after her death

testified to her saintliness. Isambard de la Pierre, also a Dominican.

Although he voted for her death, de la Pierre showed signs of pity and

compassion for his victim, and assisted her at her last moments.

Testimony to her pure character was given by him in the time of her

rehabilitation. Besides these were Emenyart, Fiexvet, Guerdon, Le

Fèvre, Delachambre, and Tiphanie, all of whom, with the exception of

the last two, who were doctors of medicine, were members of the

University. As we have already stated, out of this vast crowd of

ecclesiastics and a few laymen, only two Englishmen took part in the

trial. But the immediate guard of the prisoner was composed of English

soldiers—namely, of the following: John Gris, an English knight, one

of Henry's bodyguard, who was in personal attendance on Joan of Arc;

also John Berwoit (?) and William Talbot, subordinator to Gris. These

men commanded a set of soldiers called houspilleurs, placed in the

cell of the prisoner day and night. According to J. Bellow's pocket

dictionary, the term houspilleur is derived from the old French term

houspiller—Ang. 'to worry.' And these fellows certainly carried out

that meaning of the word.

If anything is needed to prove what an important case the English and

those allied to them in France considered that of Joan of Arc, the

great number of prelates and doctors assembled to judge her is

sufficient to show. The doctors who had been summoned to attend the

trial, and who had come to Rouen from Paris, were well paid by

Winchester. Some of the receipts are still in existence. The

Inquisition and Cauchon also received pay from the English Government.

Besides money, as we have said, Cauchon expected also to receive the

Archbishopric of Rouen for his zeal in bringing Joan of Arc to the

stake. Cupidity, lust of place and power, and fear of the enemies of

the French were the principal motives which influenced these men,

whose names should for ever be execrated. In truth, a vulgar greed

induced them to destroy one of the noblest creatures that had ever

honoured humanity.

The procès-verbal and the minutes of the trial were written in

Latin, and translated by Thomas de Courcelles; only a portion of the

original translation has been preserved. There were three reporters

who took notes during the trial—Manchon, Colles, and Taquel. The

notes in Latin, written as the trial proceeded, were collected in the

evenings, and translated into French by Manchon.

One difficult question arises—namely, are these notes to be relied

on? Manchon appears to have been honest in his writing, but Cauchon

was not to be trifled with in what he wished noted, as the following

instance will show. A sheriff's officer, named Massieu, was overheard

to say that Joan of Arc had done nothing worthy of the death sentence.

It was repeated to Cauchon, who threatened to have Massieu drowned.

When Isambert de la Pierre advised Joan to submit herself to the

Council then holding meetings at Bâle, to which she assented, Cauchon

shouted out, 'In the devil's name hold your peace!' On being asked by

Manchon whether the prisoner's wish to submit her case to the Council

at Bâle should be placed on the minutes of the trial, Cauchon roughly

refused. Joan of Arc overhearing this, said, 'You write down what is

against my interest, but not what is in my favour.' But we think the

truth comes out, on the whole, pretty clearly; and we have in the

answers of Joan to her judges, however much these answers may have

been altered to suit Cauchon's views and ultimate object, a splendid

proof of her presence of mind and courage. This she maintained day

after day in the face of that crowd of enemies who left no stone

unturned, no subtlety of law or superstition disused, to bring a

charge of guilt against her.

No victory of arms that Joan of Arc might have accomplished, had her

career continued one bright and unclouded success, could have shown in

a grander way the greatness of her character than her answers and her

bearing during the entire course of her examinations before her

implacable enemies, her judicial murderers.

After holding some preliminary and private meetings, in which Cauchon,

with some of the prelates, drew up a series of articles of indictment

against the prisoner, the first public sitting of the tribunal took

place in the chapel of the castle, in the same building in which Joan

was imprisoned.

This was on the 21st of February, 1431. As we have said, from the day

of her arrival in Rouen, at the end of December of the previous year,

till this 21st day of February, Joan had been kept in an iron cage—a

martyrdom of fifty days' daily and nightly torture. During the trial

her confinement was less barbarous, but she was kept chained to a

wooden bed, and the only wonder is that she did not succumb to this

barbarous imprisonment. We shall see that she fell seriously ill, and

the English at one time feared she would die a natural death, and

defeat their object of having her exposed and destroyed as a witch and

a heretic.

On the day before the meeting of the tribunal, Cauchon sent summonses

for all the judges to attend. Joan of Arc had meanwhile made two

demands, both of which were refused. One was, that an equal number of

clergy belonging to the French party should form an equal number in

the tribunal to those of the English faction. The other demand was

that she should be allowed to hear Mass before appearing before the

tribunal.

At eight in the morning of Wednesday, the 21st of February, Cauchon

took his seat as presiding judge for the trial about to commence.

Beneath him were ranged forty-three assessors—there were ninety-five

assessors in all who took part in the trial. On the public days their

numbers varied from between forty to sixty.

The prisoner was led into the chapel by the priest Massieu. Cauchon

opened the proceedings with the following harangue:—

'This woman,' he said, pointing to Joan of Arc, 'this woman has been

seized and apprehended some time back, in the territory of our diocese

of Beauvais. Numerous acts injurious to the orthodox faith have been

committed by her, not merely in our diocese, but in many other

regions. The public voice which accuses her of such crimes has become

known throughout Christendom, and quite recently the high and very

Christian Prince, our lord the King, has delivered her up and given

her in our custody in order that a trial in the cause of religion

shall be made, as it seemeth right and proper. For as much in the eyes

of public opinion, and owing to certain matters which have come to our

knowledge'—(Cauchon here refers to the information that he sought to

obtain from Domremy: as nothing could be learnt there but what

redounded to Joan of Arc's credit, no further use was made of the

information by the Bishop)—'we have, with the assistance of learned

doctors in religious and civil law, called you together in order to

examine the said Joan, in order that she be examined on matters

relating to faith. Therefore,' he continued, 'we desire in this trial

that you fill the duty of your office for the preservation and

exaltation of the Catholic faith; and, with the Divine assistance of

our Lord, we call upon you to expedite these proceedings for the

welfare of your consciences, that you speak the plain and honest

truth, without subterfuge or concealment, on all questions that will

be made you touching the faith. And in the first place we call upon

you to take the oath in the form prescribed. Swear, the hands placed

on the Gospels, that you will answer the truth in the questions that

will be asked you.'

The latter words the Bishop had addressed to Joan; who answered that

she knew not on what Cauchon would question her. 'Perhaps,' she said,

'you will ask me things about which I cannot answer you.'

'Will you swear,' said Cauchon, 'to tell the truth respecting the

things which will be asked you concerning the faith, and of which you

are cognisant?'

'Of all things regarding my family, and what things I have done since

coming into France, I will gladly answer; but, as regards the

revelation which I have received from God, I have never revealed to

any one, except to Charles my King, and I will never reveal these

things, even if my head were to be cut off, because my voices have

ordered me not to confide these things to any one save the King. But,'

she continued, 'in eight days' time I shall know whether or not I may

be allowed to tell you about them.'

Cauchon then repeated his question to the prisoner, namely, whether

she would answer any questions put to her regarding matters of faith,

and the Gospels were placed before her. The prisoner, kneeling, laid

her hands upon them, and swore to speak the truth in what was asked

her as regarded matters of faith.

'What is your name?' asked Cauchon.

J.—'In my home I was called Jeannette. Since I came to France I was

called Joan. I have no surname.'

C.—'Where were you born?'

J.—'At Domremy, near Greux. The principal church is at Greux.'

C.—'What are your parents' names?'

J.—'My father's name is James d'Arc; my mother's, Isabella.'

C.—'Where were you baptized?'

J.—'At Domremy.'

Cauchon then asked her the names of her god-parents, who baptized her,

her age (she was about nineteen), and what her education amounted to.

'I have learnt,' Joan said, in answer to the last question, 'from my

mother the Paternoster, the Ave Maria, and the Belief. All that I know

has been taught me by my mother.'

Cauchon then called upon her to repeat the Lord's Prayer.

In trials for heresy the prisoners had to repeat this prayer before

the judges. At the commencement of Joan of Arc's trial the crime of

magic was brought against her, but as Cauchon completely failed to

find any evidence for such a charge against his prisoner, he altered

the charge of magic into one of heresy. It was probably supposed that

a heretic would be unable to repeat the prayer and the creed, being

under diabolic influence.

Joan of Arc then asked whether she might make her confession before

the tribunal. Cauchon refused this request, but told her that he would

send some one to whom she might confess. He then warned her that if

she were to leave her prison she would be condemned as a heretic.

Considering the way she was chained to her cell, it sounds strange

that Cauchon should fear her flight.

'I have never,' the Maid said, 'given my promise not to attempt to

escape if I can.'

'Have you anything to complain about?' asked the Bishop; and Joan then

said how cruelly she was fastened by chains round her body and her

feet. Probably, had she then promised not to escape from prison, this

severity would have been relaxed, but Joan of Arc had not the spirit

to stoop to her persecutors; she would not give her word not to get

free if she could. 'The hope of escape is allowed to every prisoner,'

she bravely said.

At the close of the sitting, John Gris, the English knight who had the

chief charge over the prisoner, with the two soldiers Berwoit and

Talbot, were called, and took an oath not to allow the prisoner to see

any one without Cauchon's permission, and to strictly guard the

prisoner. And with that the first day's trial ended.

Manchon, in his minutes on the day's proceedings, says that shouts and

interruptions interfered with the reporters and their notes, and that

Joan of Arc was repeatedly interrupted. Cauchon had placed some of his

clerks behind the tapestry in the depth of a window of the chapel,

whose duty it was to make a garbled copy of Joan of Arc's answers to

suit the Bishop.

Possibly finding the chapel of the castle too small for the number of

people present at the trial, the next meeting of the judges was held

in a different place, more suitable—namely, in the great hall of the

castle. That second day's trial took place on the 22nd of February.

The tribunal consisted of Cauchon and forty-seven assessors.

Cauchon commenced the proceedings by introducing John Lemaître, vicar

of the Inquisition, to the judges, after which Joan was brought into

the hall—a splendid chamber used on happier occasions for festivities

and Court pageants.

Cauchon again commanded the prisoner to take the oath, as on the first

day's trial. She said that she had already once sworn to speak nothing

but the truth, and that that should suffice. Cauchon still insisted,

and again Joan replied that as far as any question was put to her

regarding faith and religion she had promised to answer, but that she

could not promise more, and Cauchon failed to get anything more from

her.

The Bishop then applied to one of the doctors of theology to examine

and cross-question the prisoner. This man's name was Beaupère.

B.—'In the first place, Joan, I will exhort you to tell the truth, as

you have sworn to do, on all that I may have to ask you.'

J.—'You may ask me questions on which I shall be able to answer you,

and on others about which I cannot. If you were well informed about me

you should wish me out of your power. All that I have done has been

the work of revelation.'

B.—'How old were you when you left your home?'

J.—'I do not exactly know.'

B.—'Did you learn any trade at home?'

J.—'Yes, to sew and to spin, and for that I am not afraid to be

matched by any woman in Rouen?'

B.—'Did you not once leave your father's house before you left it

altogether?'

J.—'We left for fear of the Burgundians, and I once left my father's

house and went to Neufchâteau in Lorraine, to visit a woman named La

Rousse, where I remained for fifteen days.'

B.—'What was your occupation when at home?'

J.—'When I was with my father I looked after the household affairs,

and I went but seldom with the sheep and cattle to the fields.'

B.—'Did you make your confession every year?'

J.—'Yes, to my curate, and when he was prevented hearing it, to

another priest, with my curate's permission. I think on two or three

occasions I have confessed to mendicant friars. That happened at

Neufchâteau. I took the Communion at Easter.'

B.—'Have you received the Eucharist at other festivals besides that

of Easter?'

Joan of Arc said that what she had already told regarding this

question was sufficient.

'Passez outre' is the term she used, not an easy one to translate.

Perhaps 'that will suffice' is like it.

Beaupère now began questioning Joan of Arc regarding 'her voices,' and

one can imagine how eagerly this portion of the prisoner's examination

must have been listened to by all present.

'When did you first hear the voices?' asked Beaupère.

'I was thirteen,' answered Joan, 'when I first heard a voice coming

from God to help me to live well. That first time I was much alarmed.

The voice came to me about mid-day; it was in the summer, and I was in

my father's garden.'

'Had you been fasting?' asked Beaupère.

J.—'Yes, I had been fasting.'

B.—'Had you fasted on the day before?'

J.—'No, I had not.'

B.—'From what direction did the voices come?'

J.—'I heard the voice coming from my right—from towards the church.'

B.—'Was the voice accompanied with a bright light?'

J.—'Seldom did I hear it without seeing a bright light. The light

came from the same side as did the voice, and it was generally very

brilliant. When I came into France I often heard the voices very

loud.'

B.—'How could you see the light when you say it was at the side?'

To this question Joan gave no direct answer, but she said that when

she was in a wood she would hear the voices coming towards her.

'What,' next asked Beaupère, 'what did you think this voice which

manifested itself to you sounded like?'

J.—'It seemed to me a very noble voice, and I think it was sent to me

by God. When I heard it for the third time I recognised it as being

the voice of an angel.'

B.—'Could you understand it?'

J.—'It was always quite clear, and I could easily understand it.'

B.—'What advice did it give you regarding the salvation of your

soul?'

J.—'It told me to conduct myself well, and to attend the services of

the Church regularly; and it told me that it was necessary that I

should go to France.'

B.—'In what manner of form did the voice appear?'

J.—'As to that I will give you no answer.'

B.—'Did that voice solicit you often?'

J.—'It said to me two or three times a week, "Leave your village and

go to France."'

B.—'Did your father know of your departure?'

J.—'He knew nothing about it. The voice said, "Go to France," so I

could not remain at home any longer.'

B.—'What else did it say to you?'

J.—'It told me that I should raise the siege of Orleans.'

B.—'Was that all?'

J.—'The same voice told me to go to Vaucouleurs, to Robert de

Baudricourt, captain of that place, and that he would give me soldiers

to accompany me on my journey; and I answered it, that I was a poor

girl who did not know how to ride, neither how to fight.'

B.—'What did you do then?'

J.—'I went to my uncle, and told him that I wished to remain with him

for some time, and I lived with him eight days. I then told him that I

must go to Vaucouleurs, and he took me there. When I arrived there I

recognised Robert de Baudricourt, although it was the first time that

I saw him.'

B.—'How, then, did you recognise him?'

J.—'I knew him through my voices. They said to me, "This is the man,"

and I said to him, "I must go to France." Twice he refused to listen

to me. The third time he received me. The voices had told me this

would happen.'

B.—'Had you not some business with the Duke of Lorraine?'

J.—'The Duke ordered that I should be brought to him. I went and said

to him, "I must go to France." The Duke asked me how he should recover

his health. I told him I knew nothing about that.'

B.—'Did you speak much to him about your journey?'

J.—'I told him very little about it. But I asked him to allow his

son, with some soldiers, to go to France with me, and that I should

pray God to cure him. I had gone to him with a safe conduct. After

leaving him I returned to Vaucouleurs.'

B.—'How were you dressed when you left Vaucouleurs?'

J.—'When I left Vaucouleurs I wore a man's dress. I had on a sword

which Robert de Baudricourt had given me, without any other arms. I

was accompanied by a knight, a squire, and four servants. We went to

the town of Saint Urban, and I passed that night in the abbey. On the

way, we passed through the town of Auxerre, where I attended mass in

the principal church. At that time I heard my voices often, with that

one of which I have already spoken.'

B.—'Tell me, now, by whose advice did you come to wear the dress of a

man?'

Joan of Arc refused to answer, in spite of being repeatedly told to do

so.

B.—'What did Baudricourt say to you when you left?'

J.—'He made them who went with me promise to take charge of me, and

as I left he said, "Go, and let come what may!"' (Advienne que

pourra!)

B.—'What do you know regarding the Duke of Orleans, now a prisoner in

England?'

J.—'I know that God protects the Duke of Orleans, and I have had more

revelations about the Duke than about any other person in the world,

with the exception of the King.'

She was now again asked as to who it was who had advised her to wear

male attire. She said it was necessary that she should dress in that

manner.

'Did your voice tell you so?' was asked her.

'I believe my voice gave me good advice,' she answered.

B.—'What did you do on arriving at Orleans?'

J.—'I sent a letter to the English before Orleans. In it I told them

to depart; a copy of this letter has been read to me here in Rouen.

There are two or three sentences in that copy which were not in my

letter. For instance, "Give back to the Maiden" should read, "Give

back to the King." Also these words, "Troop for troop" and

"Commander-in-chief," which were not in my letters.'

In this Joan of Arc was mistaken, M. Fabre points out in his Life of

the Maid of Orleans, the text being the same both in the original and

in the copy of the letter.

B.—'When at Chinon, could you see as often as you wished him you call

your King?'

J.—'I used to go whenever I wished to see my King. When I arrived at

the village of Sainte Catherine de Fierbois, I sent a messenger to

Chinon to the King. We arrived about mid-day at Chinon, and lodged at

an inn. After dinner I went to see the King at the castle.'

Either here Joan of Arc, or the reporter, which is more likely, makes

a slip, as she did not see Charles till two days after her arrival at

Chinon.

B.—'Who pointed out the King to you?'

J.—'When I entered the chamber I recognised the King from among all

the others, my voices having revealed him to me. I told the King that

I wished to go and make war on the English.'

B.—'When your voices revealed your King to you, were they accompanied

by any light?'

Joan made no answer.

B.—'Did you see any angel above the figure of the King?'

'Spare me such questions,' pleaded Joan; but the Inquisitor was not to

be so easily put off, and repeated the question again and again, until

Joan said that the King had also seen visions and heard revelations.

'What were these revelations?' asked the priest.

This Joan refused to answer, and told Beaupère that he might, if he

liked, send to Charles and ask him.

'Did you expect the King to see you?' then asked the priest.

Her answer was that the voice had promised her that the King would

soon see her after her arrival.

'And why,' asked Beaupère, 'did he receive you?'

'Those on my side,' said Joan, 'knew well that I was sent by God; they

have known and acknowledged that voice.'

'Who?' asked Beaupère.

'The King and others,' answered Joan, 'have heard the voices coming to

me. Charles of Bourbon also, and two or three others.'

(The Charles of Bourbon was the Count of Clermont.)

'Did you often hear that voice?' asked the priest.

'Not a day passes that I do not hear it,' Joan replied.

'What do you ask of it?' inquired Beaupère.

'I have never,' answered Joan, 'asked for any recompense, except the

salvation of my soul.'

'Did the voice always encourage you to follow the army?'

'The voice told me to remain at Saint Denis. I wished to remain, but

against my will the knights obliged me to leave. I would have remained

had I had my free-will.'

'When were you wounded?' asked Beaupère.

'I was wounded,' Joan answered, 'in the moat before Paris, having gone

there from Saint Denis. At the end of five days I recovered.'

'What did you attempt to do against Paris?'

Joan answered that she had made one skirmish (escarmouche) in front

of Paris.

'Was it on a feast day?' asked the priest.

'It was,' replied Joan. And on being asked if she considered it right

to make an attack on such a day, she refused to answer.

It is plain that the gist of those questions made by Beaupère was to

try and make Joan of Arc avow that her voices had given her evil

counsel. On the following day the same tactics were pursued.

The third meeting of the tribunal was held on the 24th of February, in

the same chamber. Sixty-two assessors were present. Again Cauchon

commenced by admonishing Joan to tell the truth on all subjects asked

her, and again she protested that as far as her revelations were

concerned she could give no answers. On Cauchon insisting, she said,

'Take care what you, who are my judge, undertake, for you take a

terrible responsibility on yourself, and you presume too far. It is

enough,' she added, 'that I have already twice taken the oath.'

Upon her saying this, Cauchon lost all control, and he stormed and

threatened her with instant condemnation if she refused to take the

oath.

'All the clergy in Paris and Rouen could not condemn me,' was the

proud answer, 'if they had not the right to do so.' But, as on the

previous occasions, she said she would willingly answer all questions

relating to her deeds since leaving her home, but that it would take

many days for her to tell them all. Wearied with the persistence and

threats of her arch-tormentor, Cauchon, Joan said that she had been

sent by God and wished to return to God. 'I have nothing more to do

here,' she added.

Beaupère was again ordered to cross-examine the prisoner.

He began by asking her when she had last eaten.

'Not since yesterday at mid-day,' she said. (It was then Lent.)

Beaupère then began again to question her regarding the voice. When

had she last heard it?

'On the previous day,' Joan said, 'and also on that day too.'

'At what o'clock of the day before?'

Thrice she had heard the voice in the morning, and once at the hour

of Vespers, and again when the Ave Maria was being sung.

'What were you doing,' asked Beaupère, 'when the voices called you?'

'I was sleeping,' answered Joan, 'and the voice awoke me.'

'Did it awake you by touching your arm?'

'The voice awoke me without its touching me.'

'Was it in your room?'

'Not that I know, but it was in the castle.'

'Did you acknowledge it by kneeling?'

'I acknowledged its presence by sitting up and clasping my hands. I

had begged for its help.'

'And what did it say to you?'

'It told me to answer boldly.'

'Tell us more clearly what it said to you.'

'I asked its advice in what I should answer, and bade it ask the

Saviour for counsel. And the voice said, "Answer boldly; God will help

you."'

'Had it said anything to you before you interrupted it?'

'Some words it had said which I did not clearly comprehend; but when

fully awake I understood it to tell me to answer boldly.' Then,

emboldened as it seemed by the recollection of that voice, she turned

to Cauchon and exclaimed, 'You, Bishop, you tell me that you are my

judge—have a care how you act, for in truth I am sent by God, and

your position is one of great peril.'

Then Beaupère broke in again, and asked Joan of Arc if the voice had

ever altered its advice, and whether it had told Joan not to answer

all the questions that would be put to her.

'I cannot answer you about that,' said Joan. 'I have revelations of

matters concerning the King which I shall not reveal.'

The Maid then asked whether she might wait for fifteen days, in order

that, by that time, she might know whether she might, or might not,

answer questions relating to this point.

The priest then asked whether she knew that the voice came from God.

'Yes,' she answered, 'and by this order—that,' she continued, 'I

believe as firmly as I believe the Christian religion, and that God

has saved us from the pains of hell.'

She was then asked if the voice was that of a male or of a female.

'It is a voice sent by God,' she only deigned to say to this.

Joan again asked for an interval of fifteen days, in order that she

might better be able in that time to know how much she might reveal to

her judges relating to her voices.

On being asked whether she believed the Almighty would be displeased

at her telling the whole truth, she said that she had been ordered by

the voices to reveal certain things to the King, and not to her

judges; that her voices had told her that very night many things for

the good of the King which he alone was to know.

But, asked Beaupère, could she not prevail on the voices to visit the

King?

'I know not if the voices would consent,' she answered.

'But why,' then asked Beaupère, 'does the voice not speak to the King

now, as it did formerly, when you were with him?'

'I know not if it be the wish of God,' Joan answered: 'without the

grace of God I should be able to do nothing.'

This remark, most innocent to our comprehension, was afterwards made

use of as a weapon to accuse the prisoner of the charge of heresy.

Later on in the day Beaupère asked Joan if the voice had form and

features. This the prisoner refused to answer.

'There is a saying among children,' she said, 'that one is sometimes

hanged for speaking the truth.'

On being asked by Beaupère if she was sure of being in a state of

grace—a question to which he had carefully led up, and whereby

Cauchon hoped to entrap her into a statement which might be used in

the accusation of heresy he was now framing against Joan of Arc—her

answer even disarmed the Bishop.

'If I am not, may God place me in it; if I am already, may He keep me

in it.'

When that test question had been put to the prisoner, one of the

judges, guessing the object of its being made, expostulated, to

Cauchon's rage—who roughly bade him hold his peace.

To that triumphant reply Joan of Arc added these words: 'If I am not

in God's grace I should be the most unhappy being in the world, and I

do not think, were I living in sin, that my voices would come to me.

Would,' she cried, 'that every one could hear them as well as I do

myself!'

Beaupère then asked her about her childhood, and when she had first

heard the voices. Asked if there were many people at Domremy in favour

of the Burgundians, she said she only knew of one individual. Then

came a string of questions about the fairy-well, the haunted oak-tree.

All these questions Joan fully answered. She had never, she said, seen

a fairy, nor had she heard the prophecy about the oak wood from which

a maid was to come and deliver France. When asked if she would leave

off wearing man's clothes, she said she would not, as it was the will

of Heaven for her to wear them.

The fourth day of the trial was the 27th of February. Fifty-three

judges were present. The usual attempt to make Joan take the oath was

made to the prisoner by Cauchon, and she was again cross-examined by

Beaupère. Again questioned as to her voices, she said that without

their permission she could not say what they said to her relating to

the King.

Asked if the voices came to her direct from God, or through some

intermediary channel, she answered, 'The voices are those of Saint

Catherine and Saint Margaret; they wear beautiful crowns—of this I

may speak, for they allow me to do so.' If, she added, her words were

doubted, they might send to Poitiers, where she had already been

questioned on the same subject.

'How do you distinguish one from the other?' asked Beaupère.

'By the manner in which they salute me,' Joan answered.

'How long have they been in communication with you?'

'I have been under their protection seven years,' was the answer.

Joan had referred to the succour which she had received from Saint

Michel. On being asked which of these saints was the first to appear

to her, she said it was the last named. She had seen him, she said, as

clearly as she saw Beaupère, and that he was not by himself, but in a

company of angels. When he left her she felt miserable, and longed to

have been taken with the flight of angels.

When Beaupère asked her if it was her own idea to come into France,

Joan replied in the affirmative, and also that she would sooner have

been torn to pieces by horses than have come without the will of God.

'Does He,' asked the priest, 'tell you not to wear the man's dress?

and had not Baudricourt,' he added, 'wished she should dress as a

man?'

She said it was not by man's but by God's orders that she wore the

dress of a man.

The questions again turned upon the vision and the voice.

Had an angel appeared above the head of the King at Chinon?

She answered that when she entered the King's presence, three hundred

soldiers stood in the hall, and fifty torches burnt in the great hall

of the castle, and that without counting the spiritual light within.

She was then asked respecting her examination before the clergy at

Poitiers.

'They believed,' Joan answered, 'that there was nothing in me against

matters of religion.'

Then Beaupère asked the prisoner if she had visited Sainte Catherine

de Fierbois.

'Yes,' she answered; 'I heard mass there twice in one day, on my way

to Chinon.'

'How did you communicate your message to the King?'

'I sent a letter asking him if I might be allowed to see him. That I

had come one hundred and fifty miles to bring him assistance, and that

I had much to do for him. I think,' she added, 'that I also said I

should know him amongst all those who might be present.'

'Did you then wear a sword?' asked Beaupère.

'I had one that I had taken at Vaucouleurs.'

'Had you not another one as well?'

'Yes; I had sent to the church of Fierbois, either from Troyes or

Chinon, for a sword from the back of the altar of Sainte Catherine. It

was found, much rusted.'

'How did you know there was a sword there?'

'Through my voices. I asked in a letter that the sword should be given

me, and the clergy sent me it. It lay underground—I am not certain

whether at the front or at the back of the altar. It was cleaned by

the people belonging to the church. They had a scabbard made for me;

also one was made at Tours—one of velvet, the other of black cloth. I

had also a third one for the Fierbois sword made of very strong

leather.'

'Were you wearing that sword,' asked Beaupère, 'when you were

captured?'

'No, I had not one then; I used to wear it constantly up to the time

that I left Saint Denis, after the assault on Paris.'

'What benediction did you bestow on that sword?'

'None,' said Joan; and she added, on being questioned as to her

feeling about the sword, that she had a particular liking for it, from

its having been found in the Church of Sainte Catherine, her favourite

saint.

Then Beaupère inquired whether Joan was not in the habit of placing

this sword on the altar, in order to bring it good luck.

Joan answered in the negative.

'But then,' the priest asked, 'had she not prayed that it might bring

her good fortune?'

'It is enough to know,' answered Joan, 'that I wished my armour might

bring me good fortune.'

'What had become of the Fierbois sword?' asked the priest.

'I offered up at Saint Denis,' answered Joan, 'a sword and some

armour, but not the Fierbois sword.'

'Had you it when at Lagny?' asked Beaupère.

'Yes,' answered the prisoner.

But between the time passed at Lagny and Compiègne she wore another

sword, taken from a Burgundian soldier, which she said was a good

weapon, able to deal shrewd blows. But she would not satisfy

Beaupère's curiosity as to what had become of the sword of Fierbois:

'That,' she said, 'has nothing to do with the trial.'

Beaupère next inquired as to what had become of Joan of Arc's goods.

She said her brother had her horses and her goods; she said she

believed the latter amounted to some twelve thousand écus.

'Had you not,' asked the priest, 'when you went to Orleans, a banner

or pennon? Of what colour was that?'

'My banner had a field all covered with fleurs-de-lis. In it was

represented the world, with angels on either side. It was white, made

of white cloth, of a kind called coucassin. On it was written Jesu

Maria. It was bordered with silk.'

'Which were you fondest of?' asked Beaupère,—'your banner or your

sword?'

'I loved my banner,' was the answer, 'forty times as much as I did my

sword.'

'Who painted your banner?'

This Joan would not say.

'Who bore your flag?' asked the priest.

Joan of Arc said she carried it herself when charging the enemy, 'in

order,' she added, 'to avoid killing any one. I never killed any one,'

she said.

'How many soldiers did the King give you,' asked the priest, 'when he

gave you a command?'

'Between ten and twelve thousand men,' answered Joan.

Then Beaupère questioned her regarding the relief of Orleans, and he

was told by the Maid that she first went to the redoubt of Saint Loup

by the bridge.

'Did you expect,' was the next question, 'that you would be able to

raise the siege?'

'Yes,' she was certain, Joan answered, from a revelation which she had

received, and of which she had told the King before making the

expedition.

'At the time of the assault,' asked Beaupère, 'did you not tell your

soldiers that you alone would receive all the arrows, bolts, and

stones discharged by the cannon and culverins?'

'No,' she answered, 'there were over a hundred wounded; but,' she

added, 'I said to my people, "Be assured that you will raise the

siege."'

'Were you wounded?' asked the priest.

'I was wounded,' Joan answered, 'at the assault of the fortress on the

bridge. I was struck and wounded by an arrow or a dart; but I

received much comfort from Saint Catherine, and I recovered in less

than fifteen days. I recovered, and in spite of the wound I did not

give up riding or working.'

'Did you know beforehand that you would be wounded?' asked Beaupère.

'Yes,' was the answer; 'and I had told my King I should be wounded. My

saints had told me of it.'

'In what manner were you wounded?' he asked.

'I was,' she answered, 'the first to raise a ladder against the

fortress at the bridge. While raising the ladder I was struck by the

bolt.'

'Why,' now asked the priest, 'did you not come to terms with the

English captains at Jargeau?'

'The knights about me,' she answered, 'told the English that they

could not have a truce of fifteen days, which they wanted; but that

they and their horses must leave the place at once.'

'And what did you say?'

'I told them that if they left the place with their side arms

(petites cottes) their lives would be spared. If not, that Jargeau

would be stormed.'

'Had you then consulted your voices to know whether you should accord

them that delay or not?'

Joan did not remember.

Here closed the fourth day's trial.

The fifth day of the trial took place on the 1st of March. Fifty-eight

judges were present.

The opening proceedings were the same as on the former occasions, and

Joan of Arc again professed her willingness to answer all questions

put to her regarding her deeds as readily as if she were in the

presence of the Pope of Rome himself; but, as formerly, she gave no

promise of revealing what her voices had told her.

Beaupère caught immediately at the opportunity of her having spoken of

the Pope to lay a pitfall in her path: Which Pope did she believe the

authentic one—he at Avignon or the one in Rome?

'Are there two?' she asked. This was an awkward question to those

bishops and doctors of the faith who had for so long a time encouraged

the schism in the Church.

Beaupère evaded the question, and asked her if it were true that she

had received a letter from the Count of Armagnac asking her which of

the two Popes he was bound to obey.

A copy of this letter was produced, as well as the one sent by Joan of

Arc in reply.

When she sent her answer, the Maid said, she was about to mount her

horse, and had told him she would be able better to answer his

question when at rest in Paris or elsewhere. The copy of her letter

which was now read, Joan said, did not quite agree with that she had

sent to Armagnac.

'She had not,' Joan added, 'said in her letter that what she knew was

by the inspiration of Heaven.'

Again pressed as to which of the two Popes she believed the true one,

she said that the one then in Rome was to her that one.

Questioned regarding her letter to the English before Orleans, she

acknowledged the accurateness of the copy produced, with the exception

of a slight mistake. She retracted nothing regarding this letter, and

declared that the English would, ere seven years were passed from that

time, give a more striking proof of their loss of power in France than

that which they had shown before Orleans. This prediction was

literally carried out when, in 1436, Paris opened its gates to Charles

VII., the loss of the capital being shortly after followed by the loss

of all the other English conquests, with the exception of the town of

Calais—the gains of a century of war being snatched from them in a

score of years.

'They will meet,' said Joan of Arc, 'with greater reverses than have

yet befallen them.'

When she was asked what made her speak thus, she answered that these

things had been revealed to her. The examination again turned upon her

voices and apparitions.

'Do they always appear to you in the same dress? Always in the same

form, and richly crowned?'

Similar foolish questions were then put to her. Had the saints long

hair? She did not know. And what language did they converse in with

her?

'Their language,' she replied, 'is good and beautiful.'

'What sort of voices were theirs?'

'They speak to me in soft and beautiful French voices,' she said.

'Does not Saint Margaret speak in English?'

'How should she,' was the answer, 'when she is not on the side of the

English?'

'Do they wear ear-rings?'

This Joan could not say; but the idiotic question reminded the

prisoner that Cauchon had taken a ring from her. She had worn two—one

had been taken by the Burgundians when she was captured, the other by

the Bishop. The former had been given her by her parents, the latter

by one of her brothers. This ring she asked Cauchon to give the

Church.

'Had she not,' she was asked, 'made use of these rings to heal the

sick?'

She had never done so.

It is very easy throughout all these questionings to see how eager

Cauchon and the other judges were to find some acknowledgment from the

lips of Joan of Arc, upon which they could found a charge of heresy

against her. Her visions were distorted by them into a proof of

infernal agency; even the harmless superstitions of her village home

did not escape being turned into idolatrous and infernal matters of

belief.

Had not her saints, questioned the Bishop, appeared to her beneath

the haunted oak of Domremy?—and what had they promised her besides

the re-establishment of Charles upon the throne?

'They promised,' she answered, 'to take me with them to Paradise,

which I had prayed them to do.'

'Nothing more?' queried Cauchon.

'If they made me another promise,' Joan replied, 'I am not at liberty

to say what that promise is till three months are past.'

'Did they say that you would be free in three months' time?'

That question remained unanswered, but before those three months had

passed, the heroine had been delivered by death from all earthly

sufferings.

She was again minutely questioned regarding the superstitions of her

country. Was there not growing there a certain fabulous plant, called

Mandragora? Joan of Arc knew nothing regarding such a plant—had never

seen it, and did not know the use of it. Again the apparitions were

brought forward.

'What was Saint Michel like? Was he clothed?'

'Do you think,' was the answer to this question, which could only have

occurred to a foul-minded priest, 'do you think that God cannot clothe

him?'

Other absurd questions followed—as to his hair; long or short? Had he

a pair of scales with him? As before, Joan of Arc answered these

futile, and sometimes indecent, questions with her wonderful patience.

At one moment she could not help exclaiming how supremely happy the

sight of her saints made her; it seemed as if a sudden vision of her

beloved saints had been vouchsafed her in the midst of that crowd of

persecuting priests.

She was again told to tell what the sign or secret was which she had

revealed to the King on first seeing him at Chinon; but about this she

was firm as adamant, and refused to give any information. To reveal

that sign or secret would, she felt, be not only a breach of

confidence and disloyalty between her and her King, but a crime to

divulge a sacred secret, which Charles kept sealed in his breast, and

which she was determined to utter to no one, and least of all to his

enemies.

'I have already said,' she told her judges, 'that you will have

nothing from me about that. Go and ask the King!'

Then followed questions as to the fashion of the crown that the King

had worn at Rheims: which brought the fifth day of the trial to a

close.

The sixth and last day's public examination took place on the 3rd of

March, forty-two judges present. The long series of questions were

nearly all relating to the appearance of the saints. Both questions

and answers were nearly the same as on the previous occasions, and

little more information was got from the prisoner.

After these, the subject of her dress—what she then wore, and what

she had worn—was entered upon.

'When you came to the King,' she was asked, 'did he not inquire if

your change in dress was owing to a revelation or not?'

'I have already answered,' said Joan, 'that I do not remember if he

asked me. This evidence was made known when I was at Poitiers.'

'And the doctors who examined you,' asked Beaupère, 'at Poitiers, did

they not want to know regarding your being dressed in man's clothes?'

'I don't remember,' she answered; 'but they asked me when I had first

begun to wear man's dress, and I told them that it was when I was at

Vaucouleurs.'

She was then asked whether the Queen had not asked her to leave off

wearing male clothes. She answered that that had nothing to do with

the trial.

'But,' next inquired Beaupère, 'when you were at the castle of

Beaurevoir, did not the ladies there ask you to do so?'

'Yes,' was the answer, 'and they offered to give me a woman's dress.

But the time had not yet come.' She would, she added, have yielded

sooner to the wishes of those ladies than to those of any other, the

Queen excepted.

The subject of the flags and banners used by her during her campaigns

was now entered on.

Had her standards not been copied by the men-at-arms?

'They did so at their pleasures,' she answered.

'Of what material was the banner made? If the poles were broken, were

they renewed?'

'They were,' she answered, 'when broken.'

'Did you not,' asked Beaupère, 'say that the flags made like your

banners were of good augury?'

'What I said,' answered Joan, 'to my soldiers was, that they should

attack the enemy with boldness.'

'Did you not sprinkle holy water on the banners?'

To this question Joan refused to answer.

Next she was questioned about a certain Friar Richard, the preaching

friar who had seen her at Troyes. She answered that he came to her

making the sign of the Cross, and that she told him to come up to her

without fear.