Joan of Arc

Chapter 1

THE CALL

Never perhaps in modern times had a country sunk so low as France,

when, in the year 1420, the treaty of Troyes was signed. Henry V. of

England had made himself master of nearly the whole kingdom; and

although the treaty only conferred the title of Regent of France on

the English sovereign during the lifetime of the imbecile Charles VI.,

Henry was assured in the near future of the full possession of the

French throne, to the exclusion of the Dauphin. Henry received with

the daughter of Charles VI. the Duchy of Normandy, besides the places

conquered by Edward III. and his famous son; and of fourteen provinces

left by Charles V. to his successor only three remained in the power

of the French crown. The French Parliament assented to these hard

conditions, and but one voice was raised in protest to the

dismemberment of France; that solitary voice, a voice crying in a

wilderness, was that of Charles the Dauphin—afterwards Charles VII.

Henry V. had fondly imagined that by the treaty of Troyes and his

marriage with a French princess the war, which had lasted over a

century between the two countries, would now cease, and that France

would lie for ever at the foot of England. Indeed, up to Henry's

death, at the end of August 1422, events seemed to justify such hopes;

but after a score of years from Henry's death France had recovered

almost the whole of her lost territory.

There is nothing in history more strange and yet more true than the

story which has been told so often, but which never palls in its

interest—that life of the maiden through whose instrumentality France

regained her place among the nations. No poet's fancy has spun from

out his imagination a more glorious tale, or pictured in glowing words

an epic of heroic love and transcendent valour, to compete with the

actual reality of the career of this simple village maiden of old

France: she who, almost unassisted and alone, through her intense love

of her native land and deep pity for the woes of her people, was

enabled, when the day of action at length arrived, to triumph over

unnumbered obstacles, and, in spite of all opposition, ridicule, and

contumely, to fulfil her glorious mission.

Sainte-Beuve has written that, in his opinion, the way to honour the

history of Joan of Arc is to tell the truth about her as simply as

possible. This has been my object in the following pages.

On the border of Lorraine and Champagne, in the canton of the

Barrois—between the rivers Marne and Meuse—extended, at the time of

which we are writing, a vast forest, called the Der. By the side of a

little streamlet, which took its source from the river Meuse, and

dividing it east by west, stands the village of Domremy. The southern

portion, confined within its banks and watered by its stream,

contained a little fortalice, with a score of cottages grouped around.

These were situated in the county of Champagne, under the suzerainty

of the Count de Bar.

The northern side of the village, containing the church, belonged to

the Manor of Vaucouleurs. In this part of the village, in a cottage

built between the church and the rivulet close by, Joan of Arc was

born, on or about the 6th of January, 1412. The house which now exists

on the site of her birthplace was built in 1481, but the little

streamlet still takes its course at its foot. Michelet, in his account

of the heroine, says the station in life of Joan's father was that of

a labourer; later investigations have proved that he was what we

should call a small farmer. In the course of the trial held for the

rehabilitation of Joan of Arc's memory, which yields valuable and

authentic information relating to her family as well as to her life

and actions, it appears that the neighbours of the heroine deposed

that her parents were well-to-do agriculturists, holding a small

property besides this house at Domremy; they held about twenty acres

of land, twelve of which were arable, four meadow-land, and four for

fuel. Besides this they had some two to three hundred francs kept safe

in case of emergency, and the furniture goods and chattels of their

modest home. The money thus kept in case of sudden trouble came in

usefully when the family had to escape from the English to

Neufchâteau. All told, the fortune of the family of Joan attained an

annual income of about two hundred pounds of our money, a not

inconsiderable revenue at that time; and with it they were enabled to

raise a family in comfort, and to give alms and hospitality to the

poor, and wandering friars and other needy wayfarers, then so common

in the land.

Two documents lately discovered prove Joan's father to have held a

position of some importance at Domremy. In the one, dated 1423, he is

styled 'doyen' (senior inhabitant) of the village, which gave him

rank next to the Mayor. In the other, four years later, he fills a post

which tallies with what is called in Scotland the Procurator-fiscal.

The name of the family was Arc, and much ink has been shed as to the

origin of that name. By some it is derived from the village of d'Arc,

in the Barrois, now in the department of the Haute Marne; and this

hypothesis is as good as any other.

Jacques d'Arc had taken to wife one Isabeau Romée, from the village of

Vouthon, near Domremy. Isabeau is said to have had some property in

her native village. The family of Jacques d'Arc and Isabella or

Isabeau consisted of five children: three sons, Jacquemin, Jean, and

Pierre, and two daughters, the elder Catherine, the younger Jeanne, or

Jennette, as she was generally called in her family, whose name was to

go through the ages as one of the most glorious in any land.

Well favoured by nature was the birthplace of Joan of Arc, with its

woods of chestnut and of oak, then in their primeval abundance. The

vine of Greux, which was famous all over the country-side as far back

as the fourteenth century, grew on the southern slopes of the hills

about Joan's birthplace. Beneath these vineyards the fields were

thickly clothed with rye and oats, and the meadow-lands washed by the

waters of the Meuse were fragrant with hay that had no rival in the

country. It was in these rich fields that, after the hay-making was

over, the peasants let out their cattle to graze, the number of each

man's kine corresponding with the number of fields which he owned and

which he had reaped.

The little maid sometimes helped her father's labourers, and the idea

has become general that Joan of Arc was a shepherdess; in reality, it

was only an occasional occupation, and probably undertaken by Joan out

of mere good-nature, seeing that her parents were well-to-do people.

All that we gather of Joan's early years proves her nature to have

been a compound of love and goodness. Every trait recorded of the

little maid's life at home which has come down to us reveals a mixture

of amiability, unselfishness, and charity. From her earliest years she

loved to help the weak and poor: she was known, when there was no room

for the weary wayfarer to pass the night in her parents' house, to

give up her bed to them, and to sleep on the floor, by the hearth.

She loved her mother tenderly, and in her trial she bore witness

before men to the good influence that she had derived from that

parent. Isabeau d'Arc appears to have been a devout woman, and to

have brought up her children to love work and religion. Joan loved to

sit by her mother's side for the hour together, spinning, and

doubtless listening to the stories of wars with the hereditary enemy.

When she could be of use, Joan was ever ready to lend a hand to help

her father or brothers in the rougher labours of coach-house, stable,

or farmyard, to keep watch over the flocks as they browsed by the

river-side along the meadow-lands.

Joan had not the defect of so many excellent but tedious women, who

love talk for the mere sake of talking: she seems to have been

reserved; but, as she proved later on, she was never at a loss for a

word in season, and with a few words could speak volumes. From her

childhood she showed an intense and ever-increasing devotion to things

holy; her delight in prayer became almost a passion. She never wearied

of visiting the churches in and about her native village, and she

passed many an hour in a kind of rapt trance before the crucifixes and

saintly images in these churches. Every morning saw her at her

accustomed place at the early celebration of her Lord's Sacrifice; and

if in the afternoon the evening bells sounded across the fields, she

would kneel devoutly, and commune in her heart with her divine Master

and adored saints. She loved above all things these evening bells,

and, when it seemed to her the ringer grew negligent, would bribe him

with some little gift—the worked wool from one of her sheep or some

other trifle—to remind him in the future to be more instant in his

office. That this little trait in Joan is true, we have the testimony

of the bell-ringer himself to attest.

This devotion to her religious duties had not the effect of making

Joan less of a companion to her fellow-villagers. She could not have

been so much beloved by them as she was had she held herself aloof

from them: on the contrary, Joan enjoyed to play with the lads and

village lasses; and we hear of her swiftness of foot in the race, of

her gracefulness in the village dance, either by the stream or around

an old oak-tree in the forest, which was said to be the favourite

haunt of the fairies.

Often in the midst of these sports Joan would break away from her

companions, and enter some church or chapel, where she placed garlands

of flowers around statues of her beloved saints.

Thus passed away the early years of the maiden's gentle life, among

her native fields, with nothing especially to distinguish her from her

companions beyond her goodness and piety. A great change, however, was

near at hand. The first of those mysterious and supernatural events

which played so all-important a part in the life of our heroine

occurred in the summer of 1425, when Joan was in her thirteenth year.

In her trial at Rouen, on being asked by her judges what was the first

manifestation of these visions, she answered that the first indication

of what she always called 'My voices' was that of St. Michel. It is

not a little remarkable that this vision of St. Michel, the patron

saint of the French army, should have taken place in the summer of

1425, at the time of a double defeat by land and sea of the enemy of

France, and when the Holy Mount in Normandy, crowned by the chapel

guarded by St. Michel, was once again in the hands of the French. At

the same time, Joan of Arc experienced some of the hardships of war

when the country around Domremy was overrun by the enemy; and the

little household of the Arcs had to fly for shelter to the

neighbouring village of Châteauneuf, in Lorraine.

I will pass somewhat rapidly over the visions, or rather

revelations—for, whatever doubts one may hold as to such heavenly

messengers appearing literally on this earth, no man can honestly

doubt that Joan believed as firmly in these unearthly visitants coming

from Heaven direct as she did in the existence of herself or of her

parents. On the subject of these voices and visions no one has written

with more sense than a distinguished prelate who was a contemporary of

the heroine's—namely, Thomas Basin, Bishop of Lisieux, who, in a work

relating to Joan of Arc, writes thus:—

'As regards her mission, and as regards the apparitions and

revelations that she affirmed having had, we leave to every one the

liberty to believe as he pleases, to reject or to hold, according to

his point of view or way of thinking. What is important regarding

these visions is the fact that Joan had herself no shadow of a doubt

regarding their reality, and it was their effect upon her, and not her

natural inclination, which impelled her to leave her parents and her

home to undertake great perils and to endure great hardships, and, as

it proved, a terrible death. It was these visions and voices, and they

alone, which made her believe that she would succeed, if she obeyed

them, in saving her country and in replacing her king on his throne.

It was these visions and voices which finally enabled her to do those

marvellous deeds, and accomplish what appeared to all the world the

impossible; these voices and visions will ever be connected with Joan

of Arc, and with her deathless fame and glory.'

From the year 1425 till 1428, the apparitions and voices were heard

and seen more or less frequently.

It is the year 1427: all that remains to Charles of his kingdom north

of the Loire, with the exception of Tournay, are a pitiful half-dozen

places. Among these is Vaucouleurs, near Domremy. They are defended by

a body of men under the command of a knight, Robert de Baudricourt,

who is about to play an important part in the history of Joan.

In one of her visions the maid was told to seek this knight, that

through his help she might be brought to the French Court; for the

voices had told her she might find the King and tell him her message,

by which she should deliver the land from the English, and restore him

to his throne. There had not been wanting legends and prophecies upon

the country-side which may have impressed Joan, and helped her to

believe that it was her mission to deliver France. One of the

prophecies was to the effect that a maiden from the borders of

Lorraine should save France, that this maiden would appear from a

place near an oak forest. This seemed to point directly to our

heroine. The old oak-tree haunted by the fairies, the neighbouring

country of Lorraine, were all in help of the tradition. Since the

betrayal of her husband's country by the wife of Charles VI., another

saying had been spread abroad throughout all that remained of that

small portion of France still held by the French King—namely, that

although France would be lost by a woman, a maiden should save it. Any

hope to the people in those distressful days was eagerly seized on;

and although the first prophecy dated from the mythical times of

Merlin, it stirred the people, especially when, later on, Joan of Arc

appeared among them, and her story became known.

These prophecies appear to have struck deeply into Joan's soul; they,

and her voices aiding, made her believe she was the maiden by whom her

country would be delivered from the presence of the enemy. But how was

she to make her parents understand that it was their child who was

appointed by Heaven to fulfil this great deliverance? Her father seems

to have been a somewhat harsh, at any rate a practical, parent. When

told of her intention to join the army, he said he would rather throw

her into the river than allow her to do so. An attempt was made by her

parents to induce her to marry. They tried their best, but Joan would

none of it; and bringing the case before the lawyers at Toul, where

she proved that she had never thought of marrying a youth whom her

parents required her to wed, she gained her cause and her freedom.

In order to take the first step in her mission, Joan felt it necessary

to rely on some one outside her immediate family. A distant relation

of her mother's, one Durand Laxart, who with his wife lived in a

little village then named Burey-le-Petit (now called Burey-en-Vaux),

near Vaucouleurs, was the relation in whose care she placed her fate.

With him and his wife Joan remained eight days; and it might have been

then that the plan was arranged to hold an interview with Baudricourt

at Vaucouleurs, in order to see whether that knight would interest

himself in Joan's mission.

The interview took place about the middle of the month of May (1428),

and nothing could have been less propitious. A soldier named Bertrand

de Poulangy, who was one of the garrison of Vaucouleurs, was an

eye-witness of the meeting. He accompanied Joan of Arc later on to

Chinon, and left a record of the almost brutal manner with which

Baudricourt received the Maid. From this soldier's narrative we

possess one of the rare glimpses which have come down to us of the

appearance of the heroine: not indeed a description of what would be

of such intense interest as to make known to us the appearance and

features of her face; but he describes her dress, which was that then

worn by the better-to-do agricultural class of Lorraine peasant women,

made of rough red serge, the cap such as is still worn by the

peasantry of her native place.

It is much to be regretted that no portrait of Joan of Arc exists

either in sculpture or painting. A life-size bronze statue which

portrayed the Maid kneeling on one side of a crucifix, with Charles

VII. opposite, forming part of a group near the old bridge of Orleans,

was destroyed by the Huguenots; and all the portraits of Joan painted

in oils are spurious. None are earlier than the sixteenth century, and

all are mere imaginary daubs. In most of these Joan figures in a hat

and feathers, of the style worn in the Court of Francis I. From

various contemporary notices, it appears that her hair was dark in

colour, as in Bastien Lepage's celebrated picture, which supplies as

good an idea of what Joan may have been as any pictured representation

of her form and face. Would that the frescoes which Montaigne

describes as being painted on the front of the house upon the site of

which Joan was born could have come down to us. They might have given

some conception of her appearance. Montaigne saw those frescoes on his

way to Italy, and says that all the front of the house was painted

with representations of her deeds, but even in his day they were much

injured.

When Joan at length stood before the knight of Vaucouleurs, she told

him boldly that she had come to him by God's command, and that she was

destined to give the King victory over the English. She even said that

she was assured that early in the following March this would be

accomplished, and that the Dauphin would then be crowned at Rheims,

for all these things had been promised to her through her Lord.

'And who is he?' asked de Baudricourt.

'He is the King of Heaven,' she answered.

The knight treated Joan's words with derision, and Joan herself with

insults; and thus ended the first of their interviews.

It was only in the season of Lent of the next year (March 1427) that

Joan again sought the aid of de Baudricourt. On the plea of attending

her cousin Laxart's wife's confinement, Joan returned to

Burey-le-Petit. She left Domremy without bidding her parents farewell;

but it has been recorded by one of her friends, named Mengeth, a

neighbour of the d'Arcs, that she told this woman of her intention of

going to Vaucouleurs, and recommended her to God's keeping, as if she

felt that she would not see her again. At Burey-le-Petit Joan remained

between the end of January until her departure for Chinon, on the 23rd

of February; and before taking final leave she asked and received her

parents' pardon for her abrupt departure from them.

While with the Laxarts, news reached Vaucouleurs that the English had

commenced the siege of Orleans. This intelligence brought matters to a

crisis, for with the loss of Orleans the whole of what remained to the

French King must fall into the hands of the enemy, and France felt her

last hour of independence had come.

Joan determined on again seeking an interview with Robert de

Baudricourt, and this second meeting between her and the knight, which

took place six months after the first, had far happier results. As M.

Simeon Luce has pointed out in his history of 'Jeanne d'Arc at

Domremy,' the situation both of Charles VI. and of the knight of

Vaucouleurs was far different in 1429 to what it had been when Joan

first saw de Baudricourt at Vaucouleurs in the previous year. The most

important stronghold held by the French in their ever-lessening

territory was in utmost danger of falling into the grasp of the

English; while de Baudricourt was anxiously waiting to hear whether

his protector, the Duc de Bar, whom Bedford had summoned to enter into

a treaty with the English, would not be prevailed upon to do so. If he

consented, this would make the knight's tenure of Vaucouleurs

impracticable. It was probably owing to this state of affairs that, on

her second interview with the knight of Vaucouleurs, Joan of Arc was

favourably received by him. Since the first visit to de Baudricourt by

the Maid of Domremy, her name had become familiar to many of the

people in and about Vaucouleurs. An officer named Jean de Metz has

left some record of his meeting at this time with Joan; for he was

afterwards examined among other witnesses at the time of the Maid's

rehabilitation in 1456. De Metz describes the Maid as being clothed in

a dress of coarse red serge, the same as she wore on her first visit

to Vaucouleurs. When he questioned her as to what she expected to gain

by coming again to Vaucouleurs, she answered that she had returned to

induce Robert de Baudricourt to conduct her to the King; but that on

her first visit he was deaf to her entreaties and prayers. But, she

added, she was still determined to appear before Charles, even if she

had to go to him all the way on her knees.

'For I alone,' she added, 'and no other person, whether he be King, or

Duke, or daughter of the King of Scots' (alluding to the future wife

of Charles VII.'s son, Louis XI.—Margaret of Scotland) 'can recover

the kingdom of France.'

As far as her own wishes were concerned, she said she would prefer to

return to her home, and to spin again by the side of her beloved

mother; for, she added: 'I am not made to follow the career of a

soldier; but I must go and carry out this my calling, for my Lord has

appointed me to do so.'

'And who,' asked de Metz, 'is your Lord?'

'My Lord,' answered the Maid, 'is God Himself.'

The enthusiasm of Joan seems to have at once gained the soldier's

heart. He took her by the hand, and swore that God willing he would

accompany her to the King. When asked how soon she would be ready to

start, she said that she was ready. 'Better to-day than to-morrow, and

better to-morrow than later on.'

During her second visit to Vaucouleurs, Joan remained with the same

friends as on her former visit; they appear to have been an honest

couple, of the name of Le Royer. One day while Joan was helping in

the domestic work of her hosts, and seated by the side of Catherine Le

Royer, Robert de Baudricourt suddenly entered the room, accompanied by

a priest, one Jean Fournier, in full canonicals. It appeared that the

knight had conceived the brilliant idea of finding out, through the

assistance of the holy man, whether Joan was under the influence of

good or evil spirits, before allowing her to go to the King's Court.

As may be imagined, Joan received the priest with all respect,

kneeling before him; and the good father was soon able to reassure de

Baudricourt that the evil spirits had no part or parcel in the heart

of the maid who received him with so much humility.

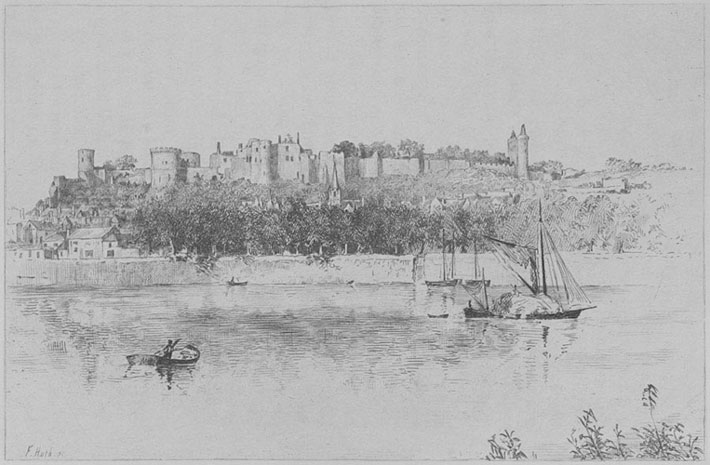

CHINON

CHINON

For three weeks Joan was left in suspense at Vaucouleurs, and probably

it was not until a messenger had been sent to Chinon and had returned

with a favourable answer, that at length de Baudricourt gave a

somewhat unwilling consent to Joan's leaving Vaucouleurs on her

mission to Chinon. During those weary weeks of anxious waiting, Joan's

hostess bore witness in after days to the manner in which the time was

passed: of how she would help Catherine in her spinning and other

homely work, but, as when at home, her chief delight was to attend the

Church services, and she would often remain to confession, after the

early communion in the church. The chapel in which she worshipped was

not the parochial church of Vaucouleurs, but was attached to the

castle, and it still exists. In that castle chapel, and in a

subterranean crypt beneath the Collegiate Church of Notre Dame de

Vaucouleurs, Joan passed much of her time. Seven and twenty years

after these events, one Jean le Fumeux, at that time a chorister of

the chapel, a lad of eleven, bore witness, at the trial in which the

memory of Joan was vindicated, to having often seen her kneeling

before an image of the Virgin. This image, a battered and rude one,

still exists. Nothing less artistic can be imagined; but no one, be

his religious views what they may, be his abhorrence of Mariolatry as

strong as that of a Calvinist, if he have a grain of sympathy in his

nature for what is glorious in patriotism and sublime in devotion, can

look on that battered and broken figure without a feeling deeper than

one of ordinary curiosity.

A short time before leaving Vaucouleurs, Joan made a visit into

Lorraine—a visit which proved how early her fame had spread abroad.

The then reigning Duke of that province, Charles II. of Lorraine, an

aged and superstitious prince, had heard of the mystic Maid of

Domremy, and he had expressed his wish to see her, probably thinking

that she might afford him relief from the infirmities from which he

suffered. Whatever the reason may have been, he sent her an urgent

request to visit him, a message with which Joan at once complied.

Accompanied by Jean de Metz, Joan went to Toul, and thence with her

cousin, Durand Laxart, she proceeded to Nancy. Little is known of her

deeds while there. She visited Duke Charles, and gave him some advice

as to how he should regain his character more than his health, over

which she said she had no control. The old Duke appears to have been

rather a reprobate, but whether he profited by Joan's advice does not

appear.

Possibly this rather vague visit of the Maid's to Nancy was undertaken

as a kind of test as to how she would comport herself among dukes and

princes. That she showed most perfect modesty of bearing under

somewhat difficult circumstances seems to have struck those who were

with her at Nancy. She also showed practical sagacity; for she advised

Duke Charles to give active support to the French King, and persuaded

him to allow his son-in-law, young René of Anjou, Duke of Bar, to

enter the ranks of the King's army, and even to allow him to accompany

her to the Court at Chinon. By this she bound the more than lukewarm

Duke of Lorraine to exert all his influence on the side of King

Charles.

Before leaving Nancy on her return to Vaucouleurs, Joan visited a

famous shrine, not far from the capital, dedicated to St. Nicolas,

after which she hastened back to Vaucouleurs to make ready for an

immediate start for Chinon.

Joan's equipment for her journey to Chinon was subscribed for by the

people of Vaucouleurs; for among the common folk there, as wherever

she was known, her popularity was great. She seems to have won in

every instance the hearts of the good simple peasantry, the poorer

classes in general, called by a saintly King of France the 'common

people of our Lord,' who believed in her long before others of the

higher classes and the patricians were persuaded to put any faith in

her. To the peasantry Joan was already the maiden pointed out in the

old prophecy then known all over France, which said that the country

would be first lost by a woman and then recovered by a maiden hailing

from Lorraine. The former was believed to be the Queen-mother, who had

sided with the English; Joan, the Maid out of Lorraine who should save

France, and by whose arm the English would be driven out of the

country.

Clad in a semi-male attire, composed of a tight-fitting doublet of

dark cloth and tunic reaching to the knees, high leggings and spurred

boots, with a black cap on her head, and a hauberk, the Maid was armed

with lance and sword, the latter the gift of de Baudricourt. Her good

friends of Vaucouleurs had also subscribed for a horse. Thus

completely equipped, she prepared for war, ready for her eventful

voyage. Her escort consisted of a knight named Colet de Vienne,

accompanied by his squire, one Richard l'Archer, two men-at-arms from

Vaucouleurs, and the two knights Bertrand de Poulangy and Jean de

Metz—eight men in all, well armed and well mounted, and thoroughly

prepared to defend their charge should the occasion arise. Nor were

precautions and means of repelling an attack unnecessary, for at this

time the country around Vaucouleurs was infested by roving bands of

soldiers belonging to the Anglo-Burgundian party. Especially dangerous

was that stretch of country lying between Vaucouleurs and Joinville,

the first of the many stages on the way to Chinon. Although the

knights and men of the small expedition were not without

apprehension, Joan seems to have shown no sign of fear: calm and

cheerful, she said that, being under the protection of Heaven, they

had nothing to fear, for that no evil could befall her.

There still exists the narrow gate of the old castle of Vaucouleurs

through which that little band rode out into the night; hard by is the

small subterranean chapel, now under repair, where Joan had passed so

many hours of her weary weeks of waiting at Vaucouleurs. The old gate

is still called the French Gate, as it was in the days of the Maid.

STREET IN CHINON

STREET IN CHINON

It was the evening of the 23rd of February, 1429, that the little band

rode away into the open country on their perilous journey. Joan,

besides adopting a military attire, had trimmed her dark hair close,

as it was then the fashion of knights to do—cut round above the ears.

Even this harmless act was later brought as an accusation against her.

Joan was then in her seventeenth year, and, although nothing but

tradition has reached us of her looks and outward form, it is not

difficult to imagine her as she rides out of that old gate, a comely

maid, with a frank, brave countenance, lit up by the flame of an

intense enthusiasm for her country and people. There can be no doubt

that by her companions in arms—rough soldiers though most of them

were—she was held in veneration; they bore testimony to their

feelings by a kind of adoration for one who seemed indeed to them more

than mortal. Wherever Joan appeared, this feeling of veneration spread

rapidly through the length and breadth of the land; and the

people were wont to speak of the future saviour of France, not by the

name of Joan the Maid, or Joan of Arc, but as the Angelic

One—'l'Angélique.'

Among the crowd who gathered to see Joan depart was de Baudricourt,

who then made amends for his rudeness and churlish behaviour on her

first visit by presenting her with his own sword, and bidding her

heartily god-speed. 'Advienne que pourra!' was his parting salute.

The journey between Vaucouleurs and Chinon occupied eleven days. Not

only was the danger of attack from the English and Burgundian soldiers

a great and a constant one, but the winter, which had been

exceptionally wet, had flooded all the rivers. Five of these had to be

crossed—namely, the Marne, the Aube, the Seine, the Yonne, and the

Loire: and most of the bridges and fords of these rivers were strictly

guarded by the enemy. The little band, for greater security, mostly

travelled during the night. Their first halt was made at the Monastery

of Saint-Urbain-les-Joinville. The Celibat of this monastery was named

Arnoult d'Aunoy, and was a relative of de Baudricourt. After leaving

that shelter they had to camp out in the open country.

Joan's chief anxiety was that she might be able to attend Mass every

day. 'If we are able to attend the service of the Church, all will be

well,' she said to her escort. The soldiers only twice allowed her the

opportunity of doing so, on one occasion in the principal church of

the town of Auxerre.

They crossed the Loire at Gien; and at that place, in the church

dedicated to one of Joan's special saints—St. Catherine, for whom she

held a personal adoration—she thrice attended Mass.

When the little band entered Touraine, they were out of danger, and

here the news of the approach of the Maid spread like wildfire over

the country-side. Even the besieged burghers of Orleans learned that

the time of their delivery from the English was at hand.

Perhaps it was when passing through Fierbois that Joan may have been

told of the existence in its church of the sword which so

conspicuously figured in her later story, and was believed to have

been miraculously revealed to her.

A letter was despatched from Fierbois to Charles at Chinon, announcing

the Maid's approach, and craving an audience. At length, on the 6th of

March, Joan of Arc arrived beneath the long stretch of castle walls of

the splendid old Castle of Chinon.

That imposing ruin on the banks of the river Vienne is even in its

present abandoned state one of the grandest piles of mediæval building

in the whole of France. Crowning the rich vale of Touraine, with the

river winding below, and reflecting its castle towers in the still

water, this time-honoured home of our Plantagenet kings has been not

inaptly compared to Windsor. Beneath the castle walls and the river,

nestles the quaint old town, in which are mediæval houses once

inhabited by the court and followers of the French and English kings.

When Joan arrived at Chinon, Charles's affairs were in a very perilous

state. The yet uncrowned King of France regarded the chances of being

able to hold his own in France as highly problematical. He had doubts

as to his legitimacy. Financially, so low were his affairs that even

the turnspits in the palace were clamouring for their unpaid wages.

The unfortunate monarch had already sold his jewels and precious

trinkets. Even his clothes showed signs of poverty and patching, and

to such a state of penury was he reduced that his bootmaker, finding

that the King was unable to pay him the price of a new pair of boots,

and not trusting the royal credit, refused to leave the new boots, and

Charles had to wear out his old shoe-leather. All that remained in the

way of money in the royal chest consisted of four gold 'écus.' To such

a pitch of distress had the poor King, who was contemptuously called

by the English the King of Bourges, sunken.

Now that Orleans was in daily peril of falling into the hands of the

English, and with Paris and Rouen in their hold, the wretched

sovereign had serious thoughts of leaving his ever-narrowing territory

and taking refuge either in Spain or in Scotland. Up to this time in

his life Charles had shown little strength of character. His existence

was passed among a set of idle courtiers. He had placed himself and

his broken fortunes in the hands of the ambitious La Tremoïlle, whose

object it was that the King should be a mere cipher in his hands, and

who lulled him into a false security by encouraging him to continue a

listless career of self-indulgence in his various palaces and pleasure

castles on the banks of the Loire. Charles had, indeed, become a mere

tool in the hands of this powerful minister. The historian Quicherat

has summed up George de la Tremoïlle's character as an avaricious

courtier, false and despotic, with sufficient talent to make a name

and a fortune by being a traitor to every side. That such a man did

not see Joan of Arc's arrival with a favourable eye is not a matter of

surprise, and La Tremoïlle seems early to have done his utmost to

undermine the Maid's influence with his sovereign. From the day she

arrived at Chinon, if not even before her arrival there—if we may

trust one story—an ambush was arranged by Tremoïlle to cut her off

with her escort. That plot failed, but her capture at Compiègne may be

indirectly traced to La Tremoïlle's machinations.

Those who have visited Chinon will recall the ancient and picturesque

street, named La Haute Rue Saint Maurice, which runs beneath and

parallel with the castle walls and the Vienne. Local tradition pointed

out till very recently, in this old street, the stone well on the side

of which the Maid of Domremy placed her foot on her arrival in the

town. This ancient well stone has recently been removed by the

Municipality of Chinon, but fortunately the 'Margelle' (to use the

native term) has come into reverent hands, and the stone, with its

deeply dented border, reminding one of the artistic wells in Venice,

is religiously preserved.

Of Chinon it has been said:

Chynon, petit ville,

Grande renom.

Its renown dates back from the early days of our Plantagenets, when

they lived in the old fortress above its dwellings: how Henry III.

died of a broken heart, and the fame of Rabelais, will ever be

associated with the ancient castle and town. Still, the deathless

interest of Chinon is owing to the residence of the Maid of

Domremy—as one has a better right to call her than of Orleans—in

those early days of her short career, in its burgh and castle. In or

near the street La Haute Rue Saint Maurice, hard by a square which now

bears the name of the heroine, Joan of Arc arrived at noon on Sunday,

the 6th of March.

It would be interesting to know in which of the old gabled houses Joan

resided during the two days before she was admitted to enter the

castle. Local tradition reports that she dwelt with a good housewife

('chez une bonne femme'). According to a contemporary plan of

Chinon, dated 1430, a house which belonged to a family named La Barre

was where she lodged; and although the actual house of the La Barres

cannot be identified, there are many houses in the street of Saint

Maurice old enough to have witnessed the advent of the Maid on that

memorable Sunday in the month of March 1430. Few French towns are so

rich in the domestic architecture of the better kind dating from the

early part of the fifteenth century as that of Chinon; and now that

Rouen, Orleans, and Poitiers have been so terribly modernised, a

journey to Chinon well repays the trouble. Little imagination is

required to picture the street with its crowd of courtiers and Court

hangers-on, upon their way to and from the castle above; so mercifully

have time and that far greater destroyer of things of yore dealt with

this old thoroughfare.

Two days elapsed before Joan was admitted to the presence of the King.

A council had been summoned in the castle to determine whether the

Maid should be received by the monarch. The testimony of the knights

who had accompanied the Maid from Vaucouleurs carried the day in her

favour.

While waiting to see the King, we have from Joan's own lips a

description of how her time was passed. 'I was constantly at prayers

in order that God should send the King a sign. I was lodging with a

good woman when that sign was given him, and then I was summoned to

the King.'

The church in which she passed her time in prayer was doubtless that

of Saint Maurice, close by the place at which she lodged. It owed its

origin to Henry II. of England; it is a rare and beautiful little

building of good Norman architecture, but much defaced by modern

restoration. Its age is marked by the depth at which its pavement

stands, the ground rising many feet above its present level.

A reliable account of Joan of Arc's interview with King Charles has

come down to us, as have so many other facts in her life's history,

through the witnesses examined at the time of the heroine's

rehabilitation. Foremost among these is the testimony of a priest

named Pasquerel, who was soon to become Joan's almoner, and to

accompany her in her warfare. He tells how, when Joan was on her road

to enter the castle, a soldier used some coarse language as he saw the

young Maid pass by—some rude remark which the fellow qualified with

an oath. Turning to him, the Maid rebuked him for blaspheming, and

added that he had denied his God at the very moment in which he would

be summoned before his Judge, for that within an hour he would appear

before the heavenly throne. The soldier was drowned within the hour.

At least such is the tale as told by Priest Pasquerel.

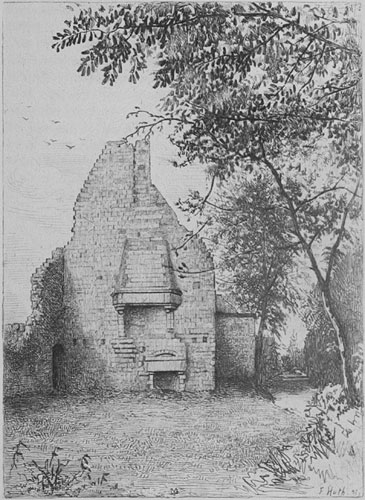

The castle was shrouded in outer darkness, but brilliantly lit within,

as Joan entered its gates. The King's Chamberlain, the Comte de

Vendôme, received the Maid at the entrance of the royal apartments,

and ushered her into the great gallery, of which fragments still

exist—a blasted fireplace, and sufficient remains of the original

stone-work to prove that this hall was the principal apartment in the

palace. Flambeaux and torches glowed from the roof and from the sides

of this hall, and here the Court had assembled, half amused, half

serious, as to the arrival of the peasant girl, about whom there had

been so much strange gossip stirring. Now the grass grows in wild

luxuriance over the pavement, and the ivy clings to the old walls of

that noble room, in which, perhaps, the most noteworthy of all

recorded meetings between king and subject then took place. A score of

torches held by pages lit the sides of the chamber. Before these were

ranged the knights and ladies, the latter clothed in the fantastically

rich costume of that time, with high erections on their heads, from

which floated long festoons of cloth, and glittering with the emblems

of their families on their storied robes. The King, in order to test

the divination of the Maid, had purposely clad himself in common garb,

and had withdrawn himself behind his more brilliantly attired

courtiers.

Ascending the flight of eighteen steps which led into the hall, and

following Vendôme, Joan passed across the threshold of the hall, and,

without a moment's hesitation singling out the King at the end of the

gallery, walked to within a few paces of him, and falling on her knees

before him—'the length of a lance,' as one of the spectators

recorded—said, 'God give you good life, noble King!' ('Dieu vous

donne bonne vie, gentil Roi').

'But,' said Charles, 'I am not the King. This,' pointing to one of his

courtiers, 'is the King.'

Joan, however, was not to be hoodwinked, and, finding that in spite of

his subterfuges he was known, Charles acknowledged his identity, and

entered at once with Joan on the subject of her mission.

HALL OF AUDIENCE - CHINON

HALL OF AUDIENCE - CHINON

It appears, from all the accounts which have come to us of this

interview, that Charles was at first somewhat loth to take Joan and

her mission seriously. He appears to have treated the Maid as a

mere visionary; but after an interview which the King gave her apart

from the crowded gallery, when she is supposed to have revealed to him

a secret known only to himself, his whole manner changed, and from

that moment Joan exercised a strong influence over the man,

all-vacillating as was his character. It has never been known what

words actually passed in this private interview between the pair, but

the subject probably was connected with a doubt that had long tortured

the mind of the King—namely, whether he were legitimately the heir to

the late King's throne. At any rate the impression Joan had produced

on the King was, after that conversation, a favourable one, and

Charles commanded that, instead of returning to her lodging in the

town, Joan should be lodged in the castle.

The tower which she occupied still exists—one of the large circular

towers on the third line of the fortifications. A gloomy-looking

cryptal room on the ground floor was probably the one occupied by

Joan. It goes by the name of Belier's Tower—a knight whose wife, Anne

de Maille, bore a reputation for great goodness among the people of

the Court. Close to Belier's Tower is a chapel within another part of

the castle grounds, but the church which in those days stood hard by

Joan's tower has long since disappeared—its site is now a mass of

wild foliage.

While Joan was at Chinon, there arrived, from his three years'

imprisonment in England, the young Duke of Anjou. Of all those who

were attached to the Court and related to the French sovereign, this

young Prince was the most sympathetic to Joan of Arc. He seems to have

fulfilled the character of some hero of romance more than any of the

French princes of that time, and Joan at once found in him a

chivalrous ally and a firm friend. That she admired him we cannot

doubt, and she loved to call him her knight.

Hurrying to Chinon, having heard of the Maid of Domremy's arrival, he

found Joan with the King. Her enthusiasm was contagious with the young

Prince, who declared how eagerly he would help her in her enterprise.

'The more there are of the blood royal of France to help in our

enterprise the better,' answered Joan.

Many obstacles had still to be met before the King accorded liberty of

action to the Maid. La Tremoïlle and others of his stamp threw all the

difficulties they could suggest in the way of Joan of Arc's expedition

to deliver Orleans: these men preferred their easy life at Chinon to

the arbitrament of battle. In vain Joan sought the King and pressed

him to come to a decision: one day he said he would consent to her

progress, and the following he refused to give his consent. He

listened to the Maid, but also to the courtiers, priests, and lawyers,

and among so many counsellors he could come to no determination.

Joan during these days trained herself to the vocation which her

career compelled her to follow. We hear of her on one occasion

surprising the King and the Court by the dexterity with which she rode

and tilted with a lance. From the young Duke of Alençon she received

the gift of a horse; and the King carried out on a large scale what de

Baudricourt had done on a small one, by making her a gift of arms and

accoutrements. Before, however, deciding to entrust the fate of

hostilities into the hands of the Maid, it was decided that the advice

and counsel of the prelates assembled at Poitiers should be taken.

It was in the Great Hall of that town that the French Parliament held

its conferences. The moment was critical, for should the decision of

these churchmen be favourable to Joan, then Charles could no longer

have any scruples in making use of her abilities, and of profiting by

her influence.

It was, therefore, determined that Joan should be examined by the

Parliament and clergy assembled at Poitiers. The King in person

accompanied the Maid to the Parliament. The majestic hall, which still

calls forth the admiration of all travellers at Poitiers, is little

changed in its appearance since the time of that memorable event. It

is one of the noblest specimens of domestic architecture in France:

its graceful pillars and arched roof, and immense fireplace, remain as

they were in the early days of the fifteenth century.

Of the proceedings of that examination unfortunately no complete

report exists. Within a tower connected with the Parliament Hall is

still pointed out a little chamber, said to have been occupied by the

Maid while undergoing this, the first of her judicial and clerical

examinations. But later investigations point to her having been lodged

in a house within the town belonging to the family of the

Parliamentary Advocate-General, Maître Jean Rabuteau.

It must have been a solemn moment for Joan when summoned for the first

time into the presence of the Court of bishops, judges, and lawyers,

whom Charles had gathered together to examine her on her visions and

on her mission. The orders had been sent out by the King and the

Archbishop of Rheims; Gerard Machot, the Bishop of Castres and the

King's confessor; Simon Bonnet, afterwards Bishop of Senlis; and the

Bishops of Macquelonne and of Poitiers. Among the lesser dignitaries

of the Church was present a Dominican monk, named Sequier, whose

account of the proceedings, and the notes kept by Gobert Thibault, an

equerry of the King, are the only records of the examination extant.

The scantiness of these accounts is all the more to be regretted,

inasmuch as Joan frequently referred to the questions made to her, and

her answers, at this trial at Poitiers, during her trial at Rouen; and

they would probably have thrown much light on the obscure passages of

her early years, for at Poitiers she had not to guard against hostile

inquisition, and, doubtless, gave her questioners a full and free

record of her past life.

TOUR D'HORLOGE - CHINON

TOUR D'HORLOGE - CHINON

The first conference between these prelates, lawyers, and Joan lasted

two hours. At first they appeared to doubt the Maid, but her frank and

straightforward answers to all the questions put her impressed them

with the truth of her character. They were, according to the old

chronicles, 'grandement ebahis comme une ce simple bergère jeune fille

pouvait ainsi repondre.'

One of her examiners, Jean Lombard by name, a professor of theology

from the University of Paris, in asking Joan what had induced her to

visit the King, was told she had been encouraged so to do by 'her

voices'—those voices which had taught her the great pity felt by her

for the land of France; that although at first she had hesitated to

obey them, they became ever more urgent, and commanded her to go.

'And, Joan,' then asked a doctor of theology named William Aymeri,

'why do you require soldiers, if you tell us that it is God's will

that the English shall be driven out of France? If that is the case,

then there is no need of soldiers, for surely, if it be God's will

that the enemy should fly the country, go they must!'

To which Joan answered: 'The soldiers will do the fighting, and God

will give the victory!'

Sequier, whose account of the proceedings has come down to us, then

asked Joan in what language the Saints addressed her.

'In a better one than yours,' she answered.

Now Brother Sequier, although a doctor of theology, had a strong and

disagreeable accent which he had brought from his native town of

Limoges, and, doubtless, the other clerks and priests tittered not a

little at Joan's answer. Sequier appears to have been somewhat

irritated, and sharply asked Joan whether she believed in God.

'Better than you do,' was the reply; but Sequier, who is described as

a 'bien aigre homme,' was not yet satisfied, and returned to the

charge. Like the Pharisees, he wished for a sign, and he declared that

he for one could not believe in the sacred mission of the Maid, did

she not show them all a sign, nor without such a sign could he advise

the King to place any one in peril, merely on the strength of Joan's

declaration and word.

To this Joan said that she had not come to Poitiers to show signs, but

she added:—

'Let me go to Orleans, and there you will be able to judge by the

signs I shall show wherefore I have been sent on this mission. Let the

force of soldiers with me be as small as you choose; but to Orleans I

must go!'

For three weeks did these conferences last. Nothing was neglected to

discover every detail regarding Joan's life: of her childhood, of her

family and her friends. And one of the Council visited Domremy to

ferret out all the details that could be got at. Needless to say, all

that he heard only redounded to the Maid's credit; nothing transpired

which was not honourable to the Maid's character and way of life, and

in keeping with the testimony Jean de Metz and Poulangy had given the

King at Chinon.

One day she said to one of the Council, Pierre de Versailles, 'I

believe you have come to put questions to me, and although I know not

A or B, what I do know is that I am sent by the King of Heaven to

raise the siege of Orleans, and to conduct the King to Rheims, in

order that he shall be there anointed and crowned.'

On another occasion she addressed the following words in a letter

which John Erault took down from her dictation—to write she knew

not—to the English commanders before Orleans: 'In the name of the

King of Heaven I command you, Suffolk [spelt in the missive Suffort],

Scales [Classidas], and Pole [La Poule], to return to England.'

One sees by the above missive that the French spelling of English

names was about as correct in the fifteenth as it is in the nineteenth

century.

What stirred the curiosity of Joan's examiners was to try and discover

whether her reported visions and her voices were from Heaven or not.

This was the crucial question over which these churchmen and lawyers

puzzled their brains during those three weeks of the blithe

spring-tide at Poitiers. How were they to arrive at a certain

knowledge regarding those mystic portents? All the armoury of

theological knowledge accumulated by the doctors of the Church was

made use of; but this availed less than the simple answers of Joan in

bringing conviction to these puzzled pundits that her call was a

heavenly one. When they produced piles of theological books and

parchments, Joan simply said: 'God's books are to me more than all

these.'

When at length it was officially notified that the Parliament approved

and sanctioned the mission of the Maid, and that nothing against her

had appeared which could in any way detract from the faith she

professed to follow out her mission of deliverance, the rejoicing in

the good town of Poitiers was extreme. The glad news spread rapidly

over the country, and fluttered the hearts of the besieged within the

walls of Orleans. The cry was, 'When will the angelic one arrive?' The

brave Dunois—Bastard of Orleans—in command of the French in that

city, had ere this sent two knights, Villars and Jamet de Tilloy, to

hear all details about the Maid, whose advent was so eagerly looked

forward to. These messengers of Dunois had seen and spoken with Joan,

and on their return to Orleans Dunois allowed them to tell the

citizens their impressions of the Maid. Those people at Orleans were

now as enthusiastic about the deliverance as the inhabitants at

Poitiers, who had seen her daily for three weeks in their midst. All

who had been admitted to her presence left her with tears of joy and

devotion; her simple and modest behaviour, blended with her splendid

enthusiasm, won every heart. Her manner and modesty, and the gay

brightness of her answers, had also won the suffrage of the priests

and lawyers, and the military were as much delighted as surprised at

her good sense when the talk fell on subjects relating to their trade.

It was on or about the 20th of April 1429 that Joan of Arc left

Poitiers and proceeded to Tours. The King had now appointed a military

establishment to accompany her; and her two younger brothers, John and

Peter, had joined her. The faithful John de Metz and Bertrand de

Poulangy were also at her side. The King had selected as her esquire

John d'Aulon; besides this she was followed by two noble pages, Louis

de Contes and Raimond. There were also some men-at-arms and a couple

of heralds. A priest accompanied the little band, Brother John

Pasquerel, who was also Joan's almoner. The King had furthermore made

Joan a gift of a complete suit of armour, and the royal purse had

armed her retainers.

During her stay at Poitiers Joan prepared her standard, on which were

emblazoned the lilies of France, in gold on a white ground. On one

side of the standard was a painting representing the Almighty seated

in the heavens, in one hand bearing a globe, flanked by two kneeling

angels, each holding a fleur-de-lis. Besides this standard, which Joan

greatly prized, she had had a smaller banner made, with the

Annunciation painted on it. This standard was triangular in form; and,

in addition to those mentioned, she had a banneret on which was

represented the Crucifixion. These three flags or pennons were all

symbolic of the Maid's mission: the large one was to be used on the

field of battle and for general command; the smaller, to rally, in

case of need, her followers around her; and probably she herself bore

one of the smaller pennons. The names 'Jesu' and 'Maria' were

inscribed in large golden letters on all the flags.

The national royal standard of France till this period had been a dark

blue, and it is not unlikely that the awe and veneration which these

white flags of the Maid, with their sacred pictures on them, was the

reason of the later French kings adopting the white ground as their

characteristic colour on military banners.

Joan never made use of her sword, and bore one of the smaller banners

into the fight. She declared she would never use her sword, although

she attached a deep importance to it.

'My banner,' she declared, 'I love forty times as much as my sword!'

And yet the sword which she obtained from the altar at Fierbois was in

her eyes a sacred weapon.

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTINUE TO NEXT CHAPTER

Add Joan of Arc as Your Friend on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/saintjoanofarc1

|

Please Consider Shopping With One of Our Supporters!

|

|

| |