Joan of Arc Chapter 11

THE MARCH TO RHEIMS

THE battle of Patay was won on Saturday, June 18, in the afternoon. That night the army slept at or about Patay; on Sunday, after an early dinner, Joan returned to Orleans with Alençon and most of the captains. The constable withdrew apart to Beaugency, where he waited for the king's permission to come to court. All efforts to secure this were vain; Joan and Alençon begged for it, two nobles of Richemont's suite went down on their knees to La Trémoille, but the favorite was inexorable. Apparently the constable did not think himself strong enough to force his way into Charles's presence. Perhaps he did not wish to endanger the expedition to Rheims. He attempted the siege of a fortress not far from Beaugency, and, having failed through no fault of his own, returned in disgust to his estates. Never again did he meet Joan.

The news of Patay spread quickly to all parts of France. In Paris the partisans of England and Burgundy were in great fear. On Tuesday, when the news of the battle reached the city, there was a riot, and many believed that the victorious French were close on the heels of the English fugitives. It was still dangerous to be called an Armagnac, but it was whispered about the city that the English had been routed almost without resistance, and men's fear of them was therefore much lessened.

On the other hand, when the mayor of La Rochelle received the bulletin sent by Charles, he ordered at once that all the bells should be rung, that all citizens should assemble in their parish churches to hear a Te Deum, and that bonfires should be lighted at the corners of the streets. On the next day there was a general procession to the church of Our Lady, and each child in La Rochelle was bribed by a cake to run before the crowd and shout "Noel" for joy.

In Orleans, as was natural, the joy was greatest. The people poured out to welcome Joan, and filled the churches, thanking "God, the Virgin Mary, and the blessed Saints of Paradise for the mercy and the honor which our Lord had shown to the king and to them all." At this time the agents of the duke of Orleans, acting under orders either sent by him from England or given by the Bastard in his behalf, provided for Joan clothes made of the richest stuffs, of red and green, his own colors, as if she were his champion. The blouse was green, dark green to denote his captivity; the long flowing cloak worn over it was made of fine crimson cloth of Brussels.

It may seem strange to some readers that Joan, the messenger of God, should have allowed herself to be gorgeously dressed. Probably she did not think that her mission was concerned with clothes of one sort or another. Presents of fine clothing and of rich stuffs were then common, and it was characteristic of Joan to take life as she found it, so that she was not hindered in her own work. Besides, she was no ascetic, and, like other girls everywhere, may well have taken innocent pleasure in gay colors. From the time she reached court until she became a prisoner, wherever her dress is described, it is always rich and brilliant.

The people of Orleans expected Charles to come to their city, since it was threatened no longer, and they decked their streets to welcome him. He gave no sign of leaving Sully, however, where La Trémoille had him under complete control, and so, oil Monday or Tuesday, Joan set out from Orleans and joined him, meaning to urge his instant departure for Rheims. Again there was delay and doubt. La Trémoille dreaded an advance; indeed, in the excitement of men's minds, he dreaded everything. Others honestly thought it madness to march more than a hundred miles through a hostile country full of fortified towns, with an active enemy on both flanks and in the rear. A day or two after Joan's arrival at Sully, Charles left the place for some unknown reason, crossed to the north bank of the Loire, and went to Chbteauneuf, about fifteen miles down the river, and so much nearer Orleans. Again Joan made to him a personal appeal. Little by little she was learning that even the messenger of God can do nothing if men will not heed the message. Her anxiety and discouragement touched the king, who was not an ill-natured man, and he tried to soothe her. With tears in her eyes she told him that he must not hesitate, and that he would gain his whole realm, and would shortly be crowned.

A council of war was held; moved by Joan's entreaties or directed by the courage with which she had inspired almost all Frenchmen, it decided to risk an advance.

Gien was appointed as the rendezvous, whither Charles went at once. The queen was sent for, that she, too, might be crowned, and Joan returned to Orleans to bring up the troops and munitions which had been left in that city. On Friday she also started for Gien.

Thither flocked all sorts of men from all parts of loyal France. The royal treasury was almost empty, the pay was the scantiest, but enthusiasm took the place of money and even of arms. The war had made some gentlemen of good family very poor. Bueil, one of the French leaders, tells us that he began life by eking out his rags with the washing stolen from a neighboring castle. Many of these gentlemen, much too poor to arm or to mount themselves as became their station, joined the expedition on foot armed only with bows or knives. "Each one of them," says a chronicler, "had great belief that by means of Joan much good would come to the realm of France, and so they desired earnestly to serve under her, and to learn her deeds, as if the matter were God's doing." There were wonders in the air; in Poitou men saw knights in full armor blazing with fire ride through the sky, threatening ruin to the duke of Brittany for his friendliness to the English. All Europe was curious, and letters were sent off to foreign princes, which gave full account of Joan's exploits, embellished with many myths and marvels. If La Trémoille and his friends had been willing, it was said, the royal army might have been large enough to drive the English from France. But no one dared to speak openly against the favorite, though all knew that the fault was his.

Arrived at Gien in the midst of all this excitement, Joan wrote on Saturday to the "Gentle loyal Frenchmen" of Tournai. Alone of all the cities in northern France, Tournai had been faithful to Charles; for a hundred miles about it, the country was ruled by English and Burgundians. Joan's letter to the citizens was full of her usual confidence, which had been confirmed by thedecision to march on Rheims. After telling them of her victories, "Keep yourselves good loyal Frenchmen, I pray you," she wrote; "and I pray and request that you hold yourselves ready to come to the consecration of the gentle king Charles at Rheims, where we shall come shortly. To God I commend you; may God have you in his keeping, and give you grace to maintain the good quarrel of the realm of France."

Although the expedition had been agreed upon in theory, yet there was so much dispute over its line of march as to make probable an indefinite delay. From Gien westward to the Bay of Biscay, Charles's enemies had no post on the Loire; but higher up the river, nearly south of Gien, the Anglo-Burgundians held the fortresses of Bonny, Cosne, and La Charité. The garrisons of these places, if strong enough to take the field, were so placed that they could easily cut the king's line of communications as he marched on Rheims, and therefore some of his councilors urged him to reduce these towns before his departure. In giving this advice, they talked a deal about going to Rheims by way of La Charité; but as the former is a hundred and thirty miles northeast of Gien, while the latter is forty miles to the south, it may easily be seen how great would have been the delay caused by taking this road, apart from the time needed to reduce two or three strong fortresses. Joan's voices told her that the king could reach Rheims in safety, if he would but try; both she and Alençon doubtless wished to take advantage of the English demoralization and want of troops, and so they strongly opposed any deviation from the direct line of march. 1 The fortune of war favored their plans. On Sunday, Bonny surrendered to the admiral of France, 2 and the nearest force of the enemy was thus disposed of. 3 On Monday, 4 Joan crossed the Loire with some of her troops, so as to excite the king to follow her.

On Wednesday, June 29, he, or his council for him, came to a decision, and the march began. Before describing it in detail, it is necessary to review briefly the condition of France as changed by the French successes about Orleans, and to consider the advantages and the difficulties attending an advance on Rheims.

The battle of Patay not only was a defeat for the English, but it practically destroyed their only force which was fit to take the field. The regent Bedford, both a soldier and a statesman, labored incessantly to gather fresh troops, but time was needed to bring them from England, and he could not at once interpose an army to prevent the march of Charles upon Rheims. There were cities, indeed, through or past which Charles must march, and which by an obstinate resistance might delay him until Bedford should have gathered his army, but the condition of these cities was peculiar. Most of them had fallen to the Anglo-Burgundians about the time of the treaty of Troyes (1420). Charles VI. was then king of France, recognized by Armagnacs and Anglo-Burgundians alike, though the latter

controlled his person and both claimed the exclusive right to speak in his name. The cities, therefore, made little difficulty in adhering to the treaty, though it recognized as the crazy king's heir his son-in-law Henry V., rather than his son Charles. They had no love of the Armagnac brigands and adventurers, who were in power at the Dauphin's court. Their municipal charters were treated with decent respect, for Bedford assumed to govern by law, and not as a conqueror, and therefore they made no attempt to revolt when the baby Henry, their old king's grandson, was proclaimed his successor. As the war dragged on year after year, however, their patriotism was gradually aroused. Outside of Paris the fierce partisan hatred of the Armagnacs had almost disappeared, and after the help of Heaven had been plainly given to Charles VII., few were zealous to oppose his march. The men of Champagne had no intention of revolting actively against the English rule. Officially, Charles was still their enemy; but to fight for a defeated foreigner against a victorious countryman seemed to them absurd.

It is true that there were garrisons in most of these places, commanded by captains in the pay of the English. But the garrisons were small, -- reduced, perhaps, to reinforce the army which had been defeated at Patay, -- and without help from the trained bands of the city, they were unable to offer decided resistance to Charles. Their commanders were old Burgundian partisans or noblemen who had accepted English rule. They would not betray their posts, but they could not forget that at some time they might become Charles's subjects; and, besides, they were embarrassed by the vacillation of the duke of Burgundy, to whom they looked for guidance. In a word, the obstacles to Charles's advance were very formidable to look at, and would really be formidable if at any time he should meet with a serious check; but should he meet with any decided success, they were of a sort to disappear at once and altogether.

The third element in the situation was Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy. His anger over his father's murder had cooled in ten years, and during that time he had had many disagreements with the English. More than once he had begun to negotiate with Charles and had made truces with him for part of their possessions. He seems to have had an underlying belief that at some time and somehow Charles would become king of France, -- though how much would be left of the kingdom after satisfying Philip's ambition and the claims he should choose to make on behalf of his English allies might be

uncertain. Now that Charles had met with unexpected success, Philip was urged by jealousy to draw close to Bedford. He did not answer the letter that Joan wrote him from Gien, and he joined the regent in Paris; on the other hand, he still held himself ready to treat with Charles. His vacillation perplexed everybody, and no one more than his own servants. His councilors at Dijon, probably left to their own devices, sent messengers to La Trémoille to ask what the French intended to do. The precise answer which the favorite gave we do not know, but its purport may be guessed by his subsequent action.

On leaving Gien the royal army marched against Auxerre, about fifty miles to the eastward, to which town and to others near by Charles had sent let-

ters commanding submission. One small place on the road acknowledged him; but the men of Auxerre were unwilling to do so, more because they were afraid to open their gates to an army of Armagnacs than because they were hostile to his claim to the throne. They looked to the duke of Burgundy much more than to the English. Their agents, perhaps joining those of the Burgundian council at Dijon, sought out La Trémoille and offered him money to spare the city from assault. He was able to carry out the corrupt bargain, probably by urging that Philip ought to be kept in good humor, though Joan and some of the captains declared it would be easy to take the city. Auxerre supplied the hungry army with food, made some vague promise of submission if the cities of Champagne should yield, and kept its gates safely shut. With somewhat diminished prestige and with complaints of the favorite, the army left Auxerre on July 2 or 3, and marched on Troyes, the capital of Champagne, about forty miles to the northeast.

Whatever might be the divisions in the royal army, the whole province of Champagne was greatly excited and the English partisans were much alarmed. The country was full of wild rumors. An English captain wrote to the men of Rheims that Charles was advancing by way of Montargis, some sixty miles distant from the road he actually took. In other places it was reported that Auxerre had been taken by storm and four thousand of its inhabitants put to the sword. 3 No city was sure of its neighbor. Each wondered if the other would open its gates to Charles, each feared to be the last or to set the example.

Thus the men of Troyes, on July 1, wrote to Rheim knowing that Rheims was Charles's ultimate destination,and hearing that some of its citizens had promised to open its gates to him. They themselves would do nothing of the sort, so wrote the men of Troyes, but would "uphold the cause of the king [ Henry VI.] and of the duke of Burgundy even to death inclusive." By July 4 or 5, the advancing army was come within fifteen or twenty miles of Troyes, and letters were sent forward to that city both from Charles and from Joan. The former demanded admittance and promised amnesty for all past offenses, the latter was in different style. "My very dear and good friends, if indeed you all are such," it began, "lords, burghers, and citizens of the town of Troyes, Joan the Maid in the name of the King of Heaven, her rightful and sovereign Lord, in whose royal service she daily stands, bids you give true obedience to the gentle king of France, 3 who will shortly be at Rheims and Paris, and in the good towns of his holy realm, by the aid of King Jesus, come what may. Loyal Frenchmen, come before king Charles without fail, and fear not for your bodies or your goods, if so be that you come; and if you do not come I promise you on your lives that with God's help we will enter into all the towns which belong to this holy realm, and will make a firm peace, come what may. To God I commend you. God have you in his keeping, if such be his pleasure. Answer shortly."

These letters reached Troyes, as it seems, early on the morning of July 5, and at once copies of them were sent on to Rheims, with assurances that Troyes would hold out to the death. Its people begged the menof Rheims to have pity on them, and to send to Bedford and to Burgundy for help. At about nine o'clock in the morning the advance-guard of the royal army appeared, and formally summoned Troyes to surrender. This the town council refused to do, pleading by way of excuse an oath taken to the duke of Burgundy. During the afternoon, before the investment of the city was accomplished, the councilors smuggled away another messenger with another letter to the men of Rheims, again asserting that they would resist to the death. This letter said that Joan was a fool full of the Devil, whose letter had neither rhyme nor reason, and had been thrown into the fire after being heartily laughed at. Again the men of Rheims were warned that some of their own people were traitors, and that they must be on their guard.

We shall see later what action was taken by the men of Rheims in consequence of this letter and of the rest of the correspondence.

For several days the royal army was encamped about Troyes in the hope that the city would surrender. There was some parleying and an occasional skirmish, but nothing of importance, and the burghers doubtless expected the terms granted to Auxerre. Toward the end of the week the supplies of the besiegers ran low. All realized that it was impossible to stay where they were much longer, and a council of war was held, attended by civilians as well as by the captains, but not by Joan. The archbishop of Rheims, chancellor of France, a creature of La Trémoille, spoke of the want of food and money, artillery and men, of the strength of Troyes, and of the obstinacy of its inhabitants. Gien, the base of supplies, was thirty leagues away, and the army was in peril. When he had finished, he called upon the councilors, one after another, for their opinion. Nearly all were against continuing the siege, arguing that Troyes was stronger than Auxerre, which

they had not been able to take; some were for going home, others for passing by the place and struggling on toward Rheims, with hostile fortresses in their rear. When it came to the turn of Robert le Maçon, formerly councilor of Charles VI. and once chancellor himself, he said that the march had been undertaken, in reliance neither upon the number of their troops nor upon the richness of the treasury, but because Joan the Maid advised them that such was the will of God. He suggested, therefore, that she should be called to the council. When she came in, the archbishop told her the substance of the debate, whereupon she turned to the king, and asked if she should be believed. He answered that this depended upon her words. "Good Dauphin," she said, "command your people to advance and besiege Troyes, and do not delay longer over your councils; for in God's name, before three days I will bring you into Troyes, by favor or force or valor, and false Burgundy shall be greatly amazed," The archbishop said they would wait six days for such a result, but doubted if it could be accomplished; whereat she told him not to doubt. Thereupon the council broke up.

"Immediately," says the Bastard, "she crossed the river with the royal army, pitched tents close to the walls, and labored with a diligence that not two or three most experienced and renowned captains could have shown. She worked so hard through the night that on the morrow the bishop and citizens submitted in fear and trembling. Afterwards it was found out that from the time when she advised the king not to withdraw from before the city, the citizens lost heart, and had no wish but to escape and flee to the churches." In fact, it needed but a show of resolution to destroy once for all the fictitious devotion of Troyes to the fortunes of England and Burgundy. The garrison was small; outside of it there was no real opposition to Charles, and the bishop seems to have favored him strongly. A deputation was sent to the king to treat for terms of peace. It was agreed that the soldiers should be allowed to retire with their property; that the churchmen appointed to preferment under King Henry should all be confirmed by King

Charles; that no garrison should be left in the town, no new taxes imposed; that the municipal franchises should be respected, and amnesty granted to all.

At this time there was in the city of Troyes one Friar Richard, a Franciscan, who had made much stir throughout northeastern France. During Advent he had preached in Champagne, and two or three months later had gone to Paris, where thousands of people slept on the ground over night that they might get good places to hear him the next day. He preached that Antichrist, foretold by Scripture, was already born, and he so wrought upon his hearers that in Paris more than one hundred bonfires might be seen, in which the men burnt their cards and gaming-tables, the women their headdresses and pads and gewgaws; indeed, the ten sermons which he delivered turned more people to devotion than all the sermoners who had been in Paris for a hundred years. After a few weeks he was forced to leave the city, because either his theology or his politics was suspected, and he had found his way back to Troyes, where he enjoyed a great reputation. This man, honest, fervid, emotional, living in the belief that God and Anti christ were shortly to join battle on the earth, went out of Troyes while the negotiations were going on, urged by the citizens or by his own curiosity to discover what sort of a creature this Maid might be who called herself the messenger of God.

With all his zeal, Friar Richard was not the man to neglect reasonable precautions. Only a few days before the men of Troyes had called Joan the devil's fool, or a "lyme of the Feende," as the English put it. When the friar caught sight of her, accordingly, he began to cross himself vigorously, and to sprinkle holy water. Joan's sense of the ridiculous was keen, and she told him to come on boldly, for she had no intention of flying away from him. They had some conversation together, and the good man was so completely converted that he rushed back into Troyes and loudly declared that she was a holy maid sent by God, who could, if she wished, cause the French men at arms to enter Troyes by flying over the walls. He joined himself to the royal expedition and followed Joan until, as we shall see, his love of the marvelous was tickled by a new-comer. When the Burgundians of Paris heard of his apostasy, with delightful logic they cursed God and the saints, took to gaming again, and threw into the Seine the medals he had distributed with the monogram of Jesus stamped on them.

On Sunday, July 10, Charles entered Troyes, and was royally received. As the old garrison marched away, the soldiers undertook to carry with them their prisoners, alleging that these were part of the property guaranteed by the capitulation. Joan saw the wretched men driven along; she was indignant that her countrymen should be carried into captivity before the eyes of her victorious army, and she refused to allow it. The terms of the treaty, as understood at the time, seem to have justified the garrison, however, and the king was compelled to pay the captors a reasonable ransom.

With the fall of Troyes, all opposition to Charles in Champagne collapsed. The men of Troyes wrote at once to Rheims, explaining their change of front as best they might, and calling Charles the prince of the greatest wisdom, understanding, and valor ever born to the noble house of France. On the day following its entry into Troyes, the army marched on Chblons, which within a week had declared its intention of resisting the royalists with all its might. It now eagerly opened its gates, and in a letter to Rheims, described the sweet, gracious, pitiful, and compassionate person of Charles, his noble demeanor and high understanding, and counseled the men of Rheims to send their representatives to meet him without delay.

It was not in the nature of the men of Rheims to withstand this reasoning and eloquence. Less than a fortnight before, they had professed devotion to their Anglo Burgundian rulers, and had informed them of all that went on. A little later, they had ordered a religious procession for the ambiguous purpose of moving the people to peace, love, and obedience. They had gone so far as to summon in haste to Rheims the captain of the city, who was then absent, but they had requested him to limit his escort to forty or fifty horsemen. This the captain declined to do, lest he should be made a prisoner. Assembling a considerable force, be proposed to defend the city until the duke of Burgundy should get together an army for its relief, but, after some parleying, the men of Rheims declined to admit this force within their walls. They continued, however, to listen to letters from the captain and from others, who promised help; they made light of the surrender of Troyes, and ridiculed Joan, saying that she could not bear comparison with a wellknown female fool of the duke's. When Charles actually reached Chblons, Rheims hesitated no longer. Some of the principal men of the town went to meet him at the castle of Sept Saux, about fifteen miles distant, and there received full and general pardon for all past offenses.

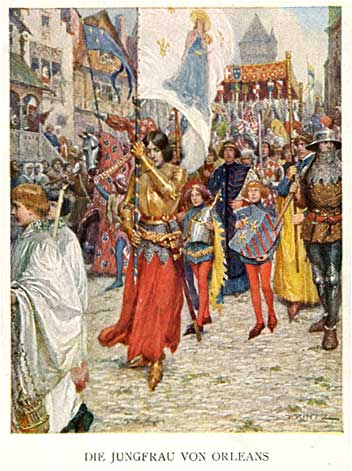

The chancellor entered his archiepiscopal city on Saturday morning; after dinner the king and Joan rode in with many councilors and captains. The burghers crowded the streets and gave them a hearty welcome, showing, as was natural, great curiosity to see Joan.

Throughout the march she had ridden armed like the other captains, sometimes with the king, sometimes in the van, sometimes covering the rear, always ready for sudden alarm or for her turn at mounting guard. She did not command the army, indeed, but at the critical moment of the campaign it was her advice that brought about the surrender of Troyes, and the demonstration against the city was made under her direction. She had the habit, about dusk, when the army was encamped for the night, of going into some church to pray. The bells were rung, the friars who followed the army gathered there, and she caused them to sing a hymn to the Virgin.

When it was possible, she slept with women,--with girls of her own age, if they could be found; otherwise she kept on her armor. If she was asked, she would stand godmother for some little baby about to be baptized. She always tried to make the soldiers lead respectable lives, but apparently without universal success, for when she was in the neighborhood of Auxerre, she broke the old sword she had received from Fierbois across the back of some loose women who followed the troops. The superstitious king, whose own loose character she was too loyal to suspect, was much irritated, and told her that she ought to use a stick instead. At Chblons she met some old acquaintances, and at Rheims she found her tier. The account given in this and in the preceding chapters is believed to describe the position Joan held in the French army with as much accuracy as is possible in a matter of the sort. The position was one not known to military treatises and it cannot be precisely defined in military terms. It was quite supplementary to any conceivable military organization. Probably Joan had not the right of military command over any one outside of her own military household, perhaps half a dozen men in all.

At the same time she assumed, and was allowed and intended to assume in certain emergencies, to command every one whom she could reach by her voice, and her advice was sometimes taken and followed, even when opposed to the conclusions previously reached by the commanding general orby a council of war. She probably attributed to herself a military rank somewhat more definite than that she really possessed. This her belief in her divine mission would naturally lead her to do. After making every possible allowance for exaggeration, and for the prejudice in her favor which existed at the time of her second trial, however, it is impossible to doubt that her common sense, courage, and vigor, as well as her claim of inspiration, gave her companions in arms great respect for her advice. To discuss her theoretical rank in the army would lead to no important conclusion; her actual position and influence must be gathered from what she actually accomplished.

Cousin Laxart and her father, who had come to see her triumph. The men of Rheims paid his expenses at the hotel of the Zebra, and gave him a horse to ride back to Domremy. 1 What passed between him and Joan is not known; at this time, perhaps, she asked and obtained his pardon for leaving her home so suddenly. It is certain that she did not forget her people. A few days later, in her favor and at her request, "considering the great, high, notable, and profitable service which she has rendered and daily renders us in the recovery of our kingdom," Charles forever exempted the people of Domremy and Greux front all taxes. For centuries the privilege lasted, and against the names of the two villages in the taxgatherer's book was written, "Nothing, for the sake of the Maid."

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTINUE TO NEXT CHAPTER

Add Joan of Arc as Your Friend on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/saintjoanofarc1

|

Please Consider Shopping With One of Our Supporters!

|

|

| |