The Trial of Jeanne D'Arc by W.P. Barrett

Joan of Arc was captured by Burgundian troops (French loyal to England) at Compiegne on May 23, 1430. In the Fall of 1430 a deal was stuck between the English and the part of the Church loyal to England to put her on trial for heresy. Joan of Arc's trial began in early 1431 after she was taken to the city of Rouen. The outcome of the trial was never in doubt but the records have proven invaluable to historians as a direct source for insights into the life of Joan of Arc. The original records were in Latin and French and have been translated into English several times by different historians. The translation below titled The Trial of Jeanne D'Arc by W.P. Barrett is one that has been highly esteemed by historians for it's accuracy and authenticity.

GO TO CONTENTS PAGE LINKING TO INDIVIDUAL CHAPTERS

THE TRIAL OF JEANNE D'ARC

GO TO CONTENTS PAGE LINKING TO INDIVIDUAL CHAPTERS

THE TRIAL OF JEANNE D'ARC

TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH

FROM THE ORIGINAL LATIN AND FRENCH DOCUMENTS

BY W. P. BARRETT

WITH AN ESSAY On the Trial of Jeanne d'Arc AND Dramatis Personae,

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF THE TRIAL JUDGES AND OTHER PERSONS

INVOLVED IN THE MAID'S CAREER, TRIAL AND DEATH

By PIERRE CHAMPION

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY COLEY TAYLOR AND RUTH H. KERR

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

FRANK P. RENNIE

GOTHAM HOUSE, INC.

1932

CONTENTS

Introduction vii

Here Begin the Proceedings 3

The Officers Appointed take Oath 26

The First Public Session 12

Thursday, February 22nd. Second Session 41

February 24th. Third Session 48

Tuesday, February 27th. Fourth Session 57

March 1st. Fifth Session 67

Saturday, March 3rd. Sixth Session 77

First Session in Prison 89

The Vicar of the Lord Inquisitor is Summoned 94

Tuesday, March 13th 103

Thursday, March 15th In Prison 119

Saturday, March 17th. In Prison 125

The Statements are Presented to the Assessors 133

Here Begins the Ordinary Trial 138

The Tenor of the Articles of Accusation.146

This Wednesday after Palm Sunday, 1431 181

Saturday, the Last Day of March, in Prison 240

The Digest is Submitted to the Assessors 243

The Tenor of the Deliberations 252

Eleven Advocates of the Court of Rouen Give their Opinions 271

Jeanne is Charitably Exhorted 285

Public Admonition of The Maid 290

She is Threatened with Torture 303

The Deliberations of the University of Paris are Read 307

Here follow the Articles concerning the Words and Deeds of Jeanne, commonly known as The Maid 315

The Deliberation and Doctrinal Judgment of the Venerable Faculty of Decrees 324

Jeanne's Faults are Expounded to Her 330

The Public Sermon. Jeanne Recants 341

Sentence after the Abjuration 346

The Trial for Relapse. Jeanne Resumes Man's Dress 349

Tuesday, May 29th 352

May 30th, the Last Day of This Trial 358

Subsequent Documents 367

Dramatis Personae by Pierre Champion 387

On the Trial of Jeanne d'Arc by Pierre Champion 475

Bibliography 541

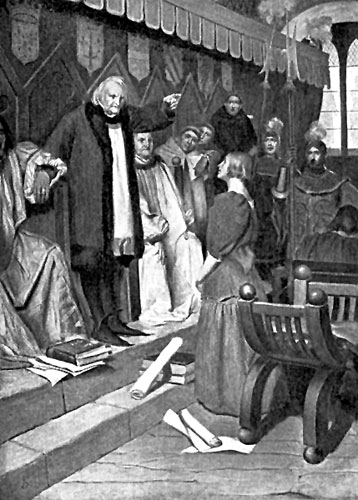

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS [Not in HTML Version]

Many came gladly, but they kissed her hands as little as she could help. frontispiece

Near the village of Domremy stands a certain large and ancient tree.35

"Go," said Robert to Jeanne, "go and come what may" 69

Jeanne entered boldly and knelt straightway before her King. 99

The Maid drove out two Daughters of Joy and thereby broke her sword 141

The Bastard of Wandomme's men seized her and tore her from her horse 169

The Demoiselle and the Lady of Beaurevoir offered her a woman's dress 199

At last she leaped and commended herself to God and Our Lady 229

She said in answer, "Men are sometimes hanged for telling the truth" 259

"Take everything peacefully, Jeanne; have no care for thy martyrdom" 289

"Bishop," said Jeanne when he came in to her, "I die through you" 319

She cried upon the name of Jesus; six times she cried out "Jhésus!" .363

INTRODUCTION

A little over five hundred years ago there was a trial in the King of England's military headquarters and capital in France -- a trial that has become second in importance only to the Trial of Christ. The young woman who was examined, tried and condemned in that medieval, strong-castled town of Rouen has been the central figure of a whole literature of controversy. Shakespeare, Voltaire, Michelet, Schiller, Quicherat, Lang, Mark Twain, Anatole France, Frank Harris, Shaw, Paine and others far too numerous to mention have demonstrated by their writing about her that minds throughout the centuries from her time to the present find her as dynamic and challenging a figure as did the people of her own time.

The Maid's followers believed that she came from God and adored her as a prophet, saint and military idol. The Burgundians and English were stricken with fear at her success and when she was captured condemned her as a witch and apostate. The Roman Catholic Church has canonized her as a saint. Mr. Shaw has hailed her as the first Nationalist and the first Protestant. Other interpretations of her personality are as completely far apart. Every book about her adds to the controversy.

Jeanne d'Arc was burned at the stake on May 30, 1431. It was not until some time later, almost certainly not before 1435

[vii]

that the record of her trial was translated by Thomas de Courcelles, one of her judges, and Guillaume Manchon, trial notary, into Latin from the minutes taken daily during the process of the trial, together with all the forms of letters patent emanating from Pierre Cauchon, Bishop of Beauvais, Jean Le Maistre, Vice Inquisitor of the Faith, the doctors of the University of Paris and other dignitaries.

Five copies were made of the official record. Manchon, the notary, wrote three in his own hand: one was given to the Inquisitor, another to the King of England, a third to Pierre Cauchon. These five copies were signed and authenticated by the notaries Manchon, Boisguillaume and Taquel, and were given the seal of the judges.

"Of these five copies," says Pierre Champion, the greatest modern authority on Jeanne d'Arc, "the one that Guillaume Manchon retained was given to the judges of the Rehabilitation proceedings on December 15, 1455 and torn up by order of that tribunal. According to the testimony of Martial d'Auvergne one of the copies had been sent to Rome; another copy was found at Orléans in 1475. Etienne Pasquier kept one copy for four years. Today there are three copies at Paris:

"A. Bibliothèque de la Chambre des Députés. ms. no. 1119, the only known copy on vellum, and of large format, which Quicherat believed destined for the King of England by Manchon. It seems more likely, by considering the variations in certain titles and headings, that this was Pierre Cauchon's copy . . . which Boisguillaume decorated. It was used in the preliminary work of the Rehabilitation and was part of the library of Parlement in the middle of the Seventeenth Century (III folios, 26x33 cm.).

"B. Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. lat. 5965, a copy carefully collated and presenting numerous changes (erasures and

[viii]

crossings-out) and writing over in different handwriting (169 folios, paper, 29 x 20 cm., traces of seals).

"C. Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. lat. 5966, a copy in uniform handwriting, without any writing over or scratching out, and of which the seals have fallen away since the time when Edmond Richer consulted it (220 folios, paper, 28 x 21 cm., traces of seals).

"These manuscripts have substantially the same value; they are authenticated copies, derived from a common original," Pierre Champion assures us, adding that the variations betray chiefly the individual habits of the scribes who transcribed them, and are therefore insignificant.

The original source of these manuscripts was the Trial Minutes in French (minuta in gallico) which the notary Manchon wrote. To quote Champion further, "With his colleagues Pierre Taquel and Boisguillaume, Manchon recorded every morning during the trial the questions and Jeanne's answers. After déjeuner, the three notaries worked in turn in putting the record in order. They had to do their work carefully, for Jeanne answered with prudence. Whenever she was asked about a point already treated upon, she did not answer anew; she had the notaries read her former answers. . . .

"These minutes, in French, formed a manuscript, paper, written entirely in Manchon's hand; he showed it to the judges of the Rehabilitation [twenty-five years later]. It was from this record that the Latin translation which we have today was made. The French minutes, produced before the judges of the Rehabilitation, we no longer have. As Quicherat was able so brilliantly to prove, we have only a fragment of it in the d'Urfé manuscript, beginning with the Twelfth Session of the trial. . . .

"If we compare Manchon's minutes with the definitive version there can be no doubt that the Latin version was built

[ ix ]

upon the minutes, of which it espouses exactly the form of the French, except for rendering the concrete and rapid words of our quick language in the more general Latin terms; we find here not French based upon Latin, but Latin based upon French. . . ." M. Champion points out, as others have, that the Latin translators, "when in despair of translating exactly, admitted the French words" used by Jeanne and her inquisitors.

This Trial Record, inconceivable as it must seem, has never, before this present translation, been completely given into English. Portions of it have been used. Many of the Maid's biographers have consulted it, summarized it, or used as much of it as suited their purposes; some have translated important and lengthy sections of it. Its details are generally known. But the whole trial has never before been accessible to the reader who is not either a French or a Latin scholar, and editions in those languages are extremely difficult to procure.

Barrett's translation, notably faithful to the original in letter and spirit, takes us into the very room with Jeanne and her judges: into the great room of the Castle of Rouen, into the tower cell where she was in chains and had to endure the cross-questioning of lawyer, skilled in subtle examination. We, as well as Jeanne, hear the formal letters of authority read out in court; the legal red tape of that day was no less ornate and magniloquent than it is at present. The court adjourns after dramatic and damning answers, to take up the burden next day or the day after. While she was "on the stand" questions were shot at her from all sides, as we may easily see for ourselves. Questions that some of her judges complain of as too subtle. She has no counsel to aid her, except her Voices, and she protests that she cannot hear Them, frequently, for the noise in the court and her prison drowns them out.

[x]

That she was tried by an extraordinary confrèrie of experts Pierre Champion's magnificent biographical researches, translated here in Dramatis Personae prove. Most of her judges were graduates and members of the faculty of the University of Paris which at that time served the church through a kind of dictatorship of the General Council. Many of them had served the King of England or his regent the Duke of Bedford, as ambassadors or councillors. Nearly all of them were at one time or another on the English payroll, directly, or indirectly through ecclesiastical appointments that were in the hands of the English King.

We see Jeanne pitted against sixty skilled politicians, lawyers, ambassadors, trained in all the complexities of legal questioning, all of them versed in academic casuistry. Most of them were avowedly her enemies. Her victories for Charles VII had driven many of them, including Bishop Cauchon, out of their dioceses, away from their seats of authority and revenue. They were of the University of Paris and Jeanne had threatened Paris. If she had succeeded in that they would have been utterly ruined.

She was imprisoned, not in the ecclesiastical prison where women would have attended her, but in the Castle of Rouen, at that time the English citadel, governed by the Earl of Warwick. The little English king lived there, and the regent Bedford. Jeanne was closely guarded and was kept in irons even when she was extremely ill. Her guards annoyed her and abused her and she lived in constant fear of them, although Warwick restrained them somewhat, for she was a valuable prisoner; the English had paid 10,000 livres for her. Ten or twelve francs was the price of a horse.

There has surely been no more dramatic or horrible trial in history than hers. Sixty of the ablest politicians and academicians, endowed with authority no less impressive because it

[xi]

was largely usurped, were summoned by their military masters to try, under the elaborate forms of law, a girt nineteen years old: an extraordinary girl whose military genius had made her the wonder of Europe, a King-maker, and the archenemy of her judges.

The world had seen nothing like her since Christ. The judges and assessors at Rouen knew as they assembled there that the eyes of Christendom were upon them and that dynasties trembled in the balance. They also were aware that the King of Heaven spoke through His saints. They knew that Jeanne had prophesied that she would raise the siege of Orléans and had done so. They knew that she had prophesied would have the Dauphin crowned at Reims. She led the Dauphin and his court through English-conquered territory to Reims, subduing Meung, Beaugency, Jargeau and Patay, and had seen him crowned Charles VII, King of France. She had captured the greatest English generals of the time. The judges as they awaited the formal opening of the trial could ponder on these wonders, and her faith that she was sent by God and Saint Michael. She was called putain, harlot, often enough by her enemies, but her judges knew that committees of women had. examined her and found her an intact virgin. The latest such examination had been conducted by the Duchess of Bedford and her ladies. Her judges must have known by rumor that at Beaurevoir, the castle of Jean de Luxembourg, who sold her to the English, the three Joans his, aunt, wife and daughter, approved of Jeanne and begged him not to sell her. The judges knew that an ecclesiastical examination at Poitiers, conducted by the Archbishop of Reims, then in exile, Cauchon's superior in the Church, had found her good and a true Catholic inspired. This examination had been held before Charles was permitted to accept her offered help. They knew, too, that Le Maistre, Vice

[xii]

Inquisitor, was hesitant about proceeding against Jeanne. With all these things in mind, the judges must have gone in fear and trembling to the opening of the trial in the heart of the English military headquarters, for all their knowledge of their authority and power. They knew what was expected of them and they knew their own abilities.

The Trial Record shows us, day by day, how they prosecuted the case, and what their individual decisions were. It is one of the most fascinating narratives in all history.

COLEY TAYLOR.

[xiii]

[Blank Page]

THE TRIAL OF JEANNE D'ARC

[Blank Page]

IN THE NAME OF THE LORD, AMEN

HERE BEGIN THE PROCEEDINGS IN MATTER OF FAITH AGAINST A DEAD WOMAN, JEANNE, COMMONLY KNOWN AS THE MAID.

To all those who shall see these present letters or public instrument, Pierre, by divine mercy Bishop of Beauvais, and brother Jean Le Maistre, of the order of Preaching brothers, deputy in the diocese of Rouen, and especially appointed in this trial to the office of the pious and venerable master Jean Graverent of the same order, renowned doctor of theology, by apostolic authority Inquisitor of the Faith and of Heretical Error in all the kingdom of France: greeting in the author and consummator of the faith, Our Lord Jesus Christ.

It has pleased divine Providence that a woman of the name of Jeanne, commonly called The Maid, should be taken and apprehended by famous warriors within the boundaries and limits of our diocese and jurisdiction. The reputation of this woman had already gone forth into many parts: how, wholly forgetful of womanly honesty, and having thrown off the bonds of shame, careless of all the modesty of womankind, she wore with an astonishing and monstrous brazenness, immodest garments belonging to the male sex; how moreover, her presumptuousness had grown until she was not afraid to

[3]

perform, to speak, and to disseminate many things contrary to the Catholic faith and hurtful to the articles of the orthodox belief. And by so doing, as well in our diocese as in several other districts of this kingdom, she was said to be guilty of no inconsiderable offenses. These things having come to the knowledge of our mother the University of Paris, and of brother Martin Billorin, vicar-general of the lord Inquisitor of Heretical Error, they immediately summoned the illustrious prince, the Duke of Burgundy and the noble lord Jean de Luxembourg, who at this time held the said woman in their power and authority, in the name of the vicar-general above mentioned, and under penalty of law, to surrender and dispatch to us, as ordinary judge, the woman so defamed and suspected of heresy.

We, the said Bishop, according to our pastoral office, desirous of promoting with all our might the exaltation and increase of the Christian faith, did resolve to institute a proper inquiry into these facts so commonly known, and so far as law and reason should persuade us, to proceed with mature deliberation to such further decisions as were incumbent upon us. We required the said prince and the said lord Jean also, under penalties of law, to surrender for trial the said woman to our spiritual jurisdiction; whilst the very serene and most Christian prince, our lord the King of France and England, summoned them to the same effect. Finally, the most illustrious lord Duke of Burgundy and the lord Jean de Luxembourg graciously consenting to these demands, and solicitous in their Catholic souls of the accomplishment of what appeared to them as helpful to the growth of the faith, surrendered and dispatched the woman to our lord the King and his commissioners. Thereafter the King in his providence, burning with a desire to succor the orthodox faith, surrendered this woman

[4]

to us, that we might, hold a complete inquiry into her acts and sayings before proceeding further, according to the ecclesiastical laws. When that was done, we requested the distinguished and notable chapter of the church of Rouen, charged with the administration of all spiritual jurisdiction in the vacancy of the archiepiscopal seat, to grant us territory in the town of Rouen for us to make this inquiry: which was graciously and freely given. But before preferring any further charge against this woman we held it wise to consult, with prolonged and mature deliberation, the opinion of experienced authorities in canon and civil law, of which, by God's grace, the number in the town of Rouen was considerable.

January 9th (1431). The First day of the Proceedings

And on Tuesday the ninth day of January in the year of our Lord fourteen hundred and thirty-one, according to the rite and computation of the Church of France, in the fourteenth year of the most Holy Father in Christ Martin V, by divine providence Pope, we the aforesaid bishop, in the house of the King's Counsel, summoned the doctors and masters whose names follow: my lord abbots Gilles of Ste. Trinité de Fécamp, doctor of sacred theology, and Nicolas de Jumièges, doctor of canon law; Pierre, prior of Longueville, doctor of theology; Raoul Roussel, treasurer of the Cathedral of Rouen, doctor of both canon and civil law; Nicolas de Venderès, archdeacon of Eu, licentiate in canon law; Robert Le Barbier, licentiate in canon and civil law; Nicolas Couppequesne, bachelor of theology, and Nicolas Loiseleur, master of arts.

Now when these men, as numerous as famous, were gathered together at the same time and place, we demanded of their wisdom the manner and the order to be followed herein,

[5]

after having shown as related above what diligence had been brought to the matter. The doctors and masters, having reached full knowledge thereof, decided that it was meet first to inquire into the acts and sayings publicly imputed to this woman; and decently deferring to their advice we declared that already certain information had been obtained at our command, and similarly decided to order more to be collected; all of which, at a certain day determined by us, should be presented to the council, that it might be more clearly informed upon the subsequent procedure necessary in the trial. And, the better and more conveniently to effect and achieve the collection of the information, it was this day decided by the aforesaid lords and masters that there was need of certain especial officers to whom this particular duty should be given. Consequently, at the counsel and deliberation of those present it was decided and decreed by us that the venerable and discreet person master Jean d'Estivet, canon of the cathedral churches of Beauvais and Bayeux, should exercise in the trial the office of Promoter or Procurator General. Master Jean de La Fontaine, master of arts and licentiate of canon law, was ordained councillor, commissary, and examiner. To the office of notaries or secretaries were designated the prudent and honest master Guillaume Colles, also called Boisguillaume, and Guillaume Manchon, priests, notaries by apostolic and imperial authority at the archiepiscopal court of Rouen; and master Jean Massieu, priest, ecclesiastical dean of Rouen, was appointed executor of the commands and convocations emanating from our authority. Further, we have had here inserted and transcribed at their order the tenor of all these letters, secret or public, that the sequence of the said acts might appear with greater clarity.

[6]

And first follows the tenor of the letter from our mother the University of Paris, addressed to the most illustrious lord Duke of Burgundy

"Most high and most puissant prince and our much feared and honored lord, we commend ourselves in all humility to your highness. Notwithstanding, most feared and honored lord, our recent letter to your highness, beseeching you in all humility that this woman known as The Maid, being by God's grace in your subjection, should be transferred into the hands of the justice of the Church that due trial might be made of her idolatries and other matters concerning our holy faith, and to repair the scandals that have arisen therefrom in our Kingdom, likewise the evils and unnumbered inconveniences which have therefrom resulted: nevertheless we have had no reply nor have we learned that any provision has been made to obtain in the affair of this woman a fitting discussion. But we greatly fear lest through the falsity and seduction of the enemy of Hell and through the malice and subtlety of evil persons, your enemies and adversaries, who put their whole might, as it is said, to effect the deliverance of this woman by subtle means, she may in some manner be taken from your subjection (which may God prevent!). For in truth in the judgment of all good informed Catholics, such a great lesion in the holy faith, such an enormous peril, obstacle or hurt to all the estate of this realm, has not occurred within human memory to compare with the escape of this woman by such damned ways without fitting reparation; but it would be in truth greatly to the prejudice of your honor and of the most Christian name of the house of France, of which you and your most noble progenitors have been and still are loyal protectors and the most noble principal members. For these reasons, most feared and sovereign lord, we beseech you again

[7]

in all humility on behalf of Our Saviour's faith, and for the conservation of the Holy Church and the protection of the divine honor, and also for the great benefit of this most Christian realm, that it may please your highness to transfer this woman into the hands of the Inquisitor of the Faith, and to dispatch her safely thither, as we formerly besought, or to surrender this woman or have her surrendered to the reverend father in God my lord bishop of Beauvais in whose spiritual jurisdiction she was apprehended, that he may try her in matter of faith, as it is reasonable and fitting for him to do to the glory of God, to the exaltation of our said holy faith, and to the profit of the good and loyal Catholics and the estate of this realm, and also to the honor and praise of your highness, whom may God keep in good prosperity and in the end grant His glory. Written. . . ." [no date].

Then follows the tenor of the letter from our said mother the University of Paris, addressed to the noble and puissant lord Jean de Luxembourg

"Most noble, honored and puissant lord, we commend ourselves lovingly to your high nobility. Your noble prudence knows well and recognizes that all good Catholic knights should employ their strength and puissance first to the service of God and then to the profit of the state. And most especially the first oath of the order of chivalry is to keep and protect the honor of God, the Catholic faith and His Holy Church. This oath you well remembered when you employed your noble power and personal presence to apprehend this woman who is called The Maid, by whom God's honor has been immeasurably offended, the Catholic faith wounded and the Church much dishonored; for through her, idolatries, errors, false doctrines and other evils and inestimable hurts have spread through the realm. In truth all loyal Christians

[8]

must cordially thank you for having rendered so great a service to our holy faith and to all the kingdom; and for our part we thank with our whole heart God and your prowess. But it would be a little thing to have done this if it were not followed by what is necessary to remedy the offense perpetrated by this woman against our sweet Creator, His faith and His Holy Church, with the other numberless misdeeds which have been told. And it would be a greater evil than ever, and a worse error would remain among the people; it would be an intolerable offense against the divine Majesty if it were to come to pass that this woman were set free, lost to us, which certain of our adversaries, it is said, would endeavor to obtain, setting to that end all their knowledge by the most subtle means, and what is worse, attempting it by silver or ransom. But we hope that God will not permit such a misfortune to visit His people, and that your good and noble providence will not suffer it, but will be able to meet the occasion fittingly; for if her deliverance took place, without appropriate reparation, it would be an irreparable dishonor to your nobility and to every one concerned: such a scandal must of necessity cease as soon as possible. And since in this matter delay is most perilous and prejudicial to the realm, on behalf of the divine honor, and for the conservation of the holy Catholic faith, and for the good and exaltation of the whole realm, we most humbly and heartily beseech that it may please your puissant and honored highness to dispatch this woman to the Inquisitor of the faith, who has urgently required and demanded her, in order to weigh the heavy charges which burden her, to the pleasure of God, and the proper edification of the people, according to good and sacred doctrine: or that it may please you to have her surrendered and delivered to the reverend father in God our most honored lord bishop of Beauvais who likewise has demanded her, and in whose jurisdiction, as has

[9]

been said, she was apprehended. The which prelate and Inquisitor are her judges in matter of faith; and every Christian is bound to obey them whatever his estate, in this case, under great legal penalties. And by so doing you gain the grace a love of the high deity; you become the instrument of the exaltation of the holy faith, and so increase the glory of your most high and noble name, with that of the high and most puissant prince our most feared lord and your own, my lord Duke of Burgundy. And every one will be charged to pray for the prosperity of your most noble person, which may 0ur Saviour, by His grace, lead and keep in all its doings and the end reward with an everlasting joy. Written . [at Paris, July 14th, 1431]

Then follows the tenor of the letter of the Vicar-General the Inquisitor addressed to the said lord Duke of Burgundy

"To the most high and puissant prince Philippe Duke of Burgundy, count of Flanders, of Artois, of Burgundy and Namur, and to all others concerned, Brother Martin, master sacred theology, and Vicar-General of the Inquisitor of the faith in the kingdom of France, greeting in Jesus Christ of true Saviour. Whereas all loyal and Christian princes and all other true Catholics are charged with extirpation of error arising against the faith, as well as scandals resulting there from among the private Christian folk, and whereas at this time it is reported and commonly said that through a certain woman named Jeanne, whom the adversaries of the kingdom call The Maid, at her instance in many cities, good towns and other places of this realm, many and diverse errors have beer sown, uttered, published and spread abroad, and still continued to be so, whence many hurts and scandals against the divine honor and against the holy faith have resulted and do result, causing the loss of souls and of many private Christians: which

[10]

cannot and must not be dissimulated nor pass without a fair and appropriate reparation. Now since it so happens that by God's grace the said Jeanne is at this time in your power and subjection, or in that of your noble and loyal vassals: for these reasons, puissant prince, we most lovingly beseech you and pray your said noble vassals to surrender the said Jeanne, through you or through them, safely and soon; and we hope that you will so do as true defenders of the faith and protectors of God's honor, and that none shall hinder or delay you (which God prevent). And with the rights of our office and the authority committed to us by the Holy See of Rome, we urgently summon and enjoin for the sake of the Catholic faith and under penalty of law all the above-said and every person of what state, condition, preëminence and authority so ever, as soon as possible with safety and fitness to send and bring captive to us the said Jeanne vehemently suspected of many crimes, and tainted with heresy, that she may appear before us against the Procurator of the Holy Inquisition, and may reply and proceed rightly according to the counsel, favor and aid of the good doctors and masters of the University of Paris, and other notable counselors therefrom. Given at Paris under our seal of office of the Holy Inquisition, the year 1430, the 26th day of May."

So signed: Lefourbeur. Hébert.

Then follows the tenor of the summons presented by us Bishop of Beauvais to the said lords, the Duke of Burgundy and Jean de Luxembourg

"This is the summons of the Bishop of Beauvais to my lord Duke of Burgundy, Jean de Luxembourg and to the Bastard of Wandomme, on behalf of the King our sovereign and of himself as Bishop of Beauvais:

"Let this woman commonly known as The Maid, a prisoner,

[11]

be sent to the King to be delivered to the Church, that she may be tried, as being suspected of and slandered with having committed many crimes, such as sorceries, idolatries, calling-up of evil spirits and many other instances touching and opposed to our faith. And although she ought not to be considered as a prisoner of war (as it appears from what is said), nevertheless to reward those who captured and held her, the King is bountifully pleased to grant them up to the sum of 6,000 francs, and to the said bastard, who captured her, will grant and assign a pension for the upkeep of his estate of 200 or 300 pounds.

"And the said Bishop himself requires the aforesaid each and every one, since the woman was captured in his diocese and under his spiritual jurisdiction, to deliver her to him that he may fittingly try her. This he is ready to undertake with the assistance of the Inquisitor of the faith, and if need be, with the assistance of doctors of theology and of decrees, and other notable persons versed in judicial matters, as the case requires, in order that it be performed in a mature, holy and due manner to the exaltation of the faith and to the instruction of many who have been deceived and abused through this woman.

"And finally, if in the above manner they do not wish or consent to obey this injunction, and although the taking of this woman is not similar to the capture of a king, of princes and others of high estate (yet if such person were captured, whether king, dauphin or other prince, the King could at his pleasure ransom him by sending to the captor ten thousand francs, according to the law and custom of France), the bishop summons and requires the abovesaid in his name and the King's to deliver The Maid to him, giving as surety the above sum of 10,000 francs, for everything whatever. And the said bishop, in his own name and according to the form and penalties

[12]

of the law, requires her to be given and delivered to him in this manner."

Then follows the instrument of the summons for the surrender of the Maid

"In the year of our Lord 1430, the 14th day of July, indiction 8, the 13th year of the pontificate of our most Holy Father the Pope Martin V, in the castle of the very illustrious prince my lord Duke of Burgundy, in his camp before Compiègne, in presence of the noble lords Nicolas de Mailly, Bailly of Vermandois and Jean de Pressy, knights, and of many other noble witnesses, in great number, there was presented by the reverend father in God my lord Pierre, by the grace of God bishop and count of Beauvais, to the very illustrious prince my lord Duke of Burgundy, a certain schedule on paper containing word for word the five articles transcribed above: the which my lord Duke gave to the noble Nicolas Rollin, knight, his chancellor, who was present; and commanded him to convey it to the noble and puissant lord Jean de Luxembourg, knight, lord of Beaurevoir, to whom, when he came, the chancellor gave the schedule, which it appeared to me he read."

So signed: "This was done in my presence, Triquellot, by apostolic authority public notary."

Follows the tenor of the letters of the University of Paris addressed to us, Bishop

"To the reverend father in God and lord bishop and count of Beauvais. We observe with amazement, reverend father and lord, the great delay in the surrender of this woman commonly called The Maid, which is so prejudicial to the faith and ecclesiastical jurisdiction, especially as she is said to be now in the hands of our lord the King. Christian princes in

[13]

their zeal for the interests of the Church and the orthodox faith are wont, when a rash assault is made upon the dogmas of this same Catholic faith, to surrender the prisoner to the ecclesiastical judges so that they may hold and punish him forthwith; and doubtless if your paternity had lent more active diligence to the pursuit of this matter, the trial of this woman would already be proceeding before an ecclesiastical court. It greatly concerns you, since you are so great a prelate of the Church, to abolish the scandals committed in our Christian religion, especially when it is a matter of the judgment of a case which chance has brought into your own diocese. Therefore, to protect the Church from the grave injury of a longer delay, will your paternity deign in its zeal to endeavor with extreme diligence to see that this woman is delivered as soon as possible into your power and that of the lord Inquisitor of Heretical Error. When you have done this, be so good as to have her safely conducted to this town of Paris, where there are many wise and learned persons, so that the trial may be diligently examined and competently conducted, to the salutary edification of the Christian people and the honor of God: may He grant you especial aid in all things, reverend father. Written at Paris in our general assembly solemnly held at St. Mathurin, November 21st, 1431. The rector and the University of Paris."

Signed: Hébert.

Follows the tenor of the letter addressed by our mother the University of Paris to our Lord the King of France and England

"To the most excellent prince, the King of France and of England, our most feared lord and father. We have recently heard that the woman called The Maid is now delivered into your power, whereat we are extremely joyful, trusting in your

[14]

good ordinance to deal with this woman according to law in order to atone for the great harm and scandals she has notoriously occasioned in this kingdom, to the great prejudice of the divine honor, our holy faith and all your good people. And because it is particularly our task as it is our profession to extirpate such manifest iniquities, especially when our Catholic faith is involved, we cannot hide the long delay in justice which must displease every good Christian, and your Majesty more than any other because of your great obligations in gratitude for the high honors, goods and dignities God has bestowed upon your excellence. But although we have several times written to you in this connection, and do so by these presents, we must humbly beseech you, most feared and sovereign lord, with our humble and loyal recommendation, to avoid the reputation of negligence in so favorable and essential a matter, and for the honor of Our Lord Jesus Christ to command that this woman shall be shortly delivered into the hands of the justice of the Church that is to the reverend father in God our most honored lord and count of Beauvais and to the Inquisitor of France, whom it particularly concerns to know these misdeeds touching our faith; for then reasonable discussion of the charges imputed to her can be made, and such reparation brought as the case demands in order to protect the holy truth of our faith and remove every false error and scandalous opinion from the hearts of your good, loyal and Christian subjects. It appears meet to us, if it were your highness's pleasure, to send this woman to this city where her trial could be notably and competently conducted: for the discussion would resound farther from here than elsewhere if it were led by the masters, doctors, and other notable persons already present, and it is proper for the reparation of the scandals to take place there where her deeds have been published and excessively notorious. By doing

[15]

this your royal majesty will remain loyal to the sovereign and divine Majesty: may He grant your excellency continual prosperity and never-ending felicity. Written at Paris in our general assembly held at St. Mathurin, November 21st 1431. Your most humble and pious daughter, the University of Paris."

Signed: Hébert

Here follows the tenor of a royal letter upon the surrender of the said woman to us, bishop of Beauvais

"Henry, by the grace of God king of France and England, to all those who shall see these present letters, greeting. It is well known how for some time a woman calling herself Jeanne the Maid, putting off the habit and dress of the female sex (which is contrary to divine law, abominable to God, condemned and prohibited by every law), has dressed and armed herself in the state and habit of man, has wrought and occasioned cruel murders, and it is said, to seduce and deceive the simple people, has given them to understand that she was sent from God and that she had knowledge of His divine secrets, with many other dangerous dogmatizations most prejudicial and scandalous to our holy faith. Whilst pursuing these abuses and exercising hostilities against us and our people, she was captured in arms before Compiègne by certain of our loyal subjects and has subsequently been led prisoner towards us. And because she has been reputed, charged and defamed by many people on the subject of superstitions, false dogmas and other crimes of divine treason, we have been most urgently required by our well beloved and loyal counselor the bishop of Beauvais, the ecclesiastical and ordinary judge of the said Jeanne, who was taken and apprehended in the boundaries and limits of his diocese, and have similarly

[16]

been exhorted by our very dear and well loved daughter the University of Paris, to surrender, present and deliver this Jeanne to the said reverend father in God, so that he may question and examine her and proceed against her according to ordinances and dispositions of canon and divine laws, when the proper assembly shall be called together. Therefore, for the respect and honor of God's name, for the protection and exaltation of His Holy Church and Catholic faith, we devoutly desire as true and humble sons of the Church to obey the requests and demands of the said reverend father in God and the exhortations of the doctors and masters of our daughter the University of Paris: and we command and grant, as often as the reverend father shall think fit, that this Jeanne shall be surrendered and delivered by our men and officers in whose hands she now is, so that he may question, examine her, and proceed against her according to God, reason, divine law and the holy canons. Therefore we command our said men and officers who guard this woman to surrender and deliver her to the said reverend father in God without contradiction or refusal, as often as he shall require, and we further command all our men of law, officers and subjects, English or French, not to occasion any hindrance or difficulty in fact or otherwise to the reverend father or any who are or shall be appointed to assist, participate in or hear the said trial, but if they are so required by the said reverend father in God they shall give them protection, aid, defense, guard and comfort, under pain of grave punishment. Nevertheless it is our intention to retake and regain possession of this Jeanne if it comes to pass that she is not convicted or found guilty of the said crimes, or certain of them concerning or touching our faith. In witness whereof we have affixed to these presents our ordinary seal in the absence of the great seal. Given

[17]

at Rouen, January 3rd, in the year of grace 1431, and the ninth of our reign."

Signed: "By the king, in his Chief Council. J. de Rinel."

Follows the tenor of the letters from the venerable chapter of the Cathedral of Rouen granting us the said bishop territory during the vacancy of the archiepiscopal see

"To all those who shall see these present letters, the chapter of the cathedral of Rouen having during the vacancy of the archiepiscopal see administration of all spiritual jurisdiction, greeting in Our Lord. On behalf of the reverend father in God and lord, Pierre, by divine mercy bishop of Beauvais, we have been informed that it is his lawful duty according to his authority as ordinary judge and otherwise, to institute an inquiry against a woman commonly called Jeanne the Maid, who abandoning all modesty, has lived a disorderly and shameful life to the scorn of the estate proper to womankind: and moreover, as is commonly known, she has sown and disseminated many opinions contrary to the Catholic faith and tending to the denigration of certain articles of the orthodox belief, wherein she appears evil-thinking, suspect, and defamed. The said bishop had proposed and resolved to institute proceedings against her since she was in his diocese and had therein committed all which was reported of her: now it came to pass according to God's pleasure that she was captured, taken and arrested in his diocese and within the limits of his spiritual jurisdiction, but that he had meanwhile been translated elsewhere. When this fact came to the knowledge of the said reverend father he of his own authority and by other means required and admonished the illustrious prince the Duke of Burgundy and the noble lord Jean de Luxembourg and the other warders of this woman to surrender her to him, for it was his lawful and reasonable duty

[18]

as the ordinary judge to institute inquiries and proceedings against this woman who, suspected of heresy, had committed so many misdemeanors against the Catholic faith, and who, it was said, had been captured, detained and arrested within the territory of his spiritual jurisdiction. These lords and the others who held Jeanne captive, being summoned to this end, both by the most Christian prince Henry our lord and king of France and England, and by our mother the University of Paris, obeyed these requisitions and demands: like faithful Catholics devoted to their faith, they surrendered and delivered this woman to our Lord the king or his commissaries, had her led to the city of Rouen where she was put into safe custody, and now, at the order and with the consent of our lord the king she has been surrendered, given up and delivered to the said reverend father in Christ. For many considerations and reasons, and especially upon careful reflection of the present circumstances, it has seemed meet to institute proceedings in this city of Rouen, according to the theological and canonical sanctions, and to carry out here the inquiries which appear necessary in this case, and, in a word, to perform all the varied business pertaining to. a suit of this kind, with all the consequent details. Certainly our bishop does not mean to put his scythe in our harvest, to act without our consent; hence he has requested us to grant him territory to assist his legal want and to perform all the acts pertaining to his suit. Therefore, approving the demand of the said reverend father, and deeming it both just and in accordance with the interests of the Catholic faith, we have granted, given and assigned him territory, and by the present letter give and assign him territory, both in this city of Rouen, and wherever in the limits of the diocese as shall appear necessary to him for all usages concerning this trial and for the execution, comprehension, decision and termination of everything pertaining

[19]

thereto. Hence we warn all our subjects, of either sex, living in the town of Rouen and in our diocese, of whatever condition, and hereby enjoin them in virtue of holy obedience, to comply with, obey and lend aid and favor to the said reverend father in all that concerns this suit, and its consequences, by supplying testimony and advice and by other means. We allow and grant that every act arising from the inquiry shall receive its full and free effect according to law, as if it had been accomplished in his own diocese of Beauvais, whether it was in fact done by his authority, by his present or future commissioners or deputies or in conjunction with the Inquisitor of Heretical Error, or his present or future deputy, either separately or in conjunction, and shall be executed and concluded. We give and grant him, so far as is necessary and God will allow, all authority and power excepting the right of the archiepiscopal dignity of the diocese of Rouen in other matters. December 28th, in the year of Our Lord 1430"

Signed: R. Guérould

Follows the tenor of the letter concerning the Promoter

"To all those who shall see these present letters, Pierre, by divine mercy bishop of Beauvais, greeting in Our Lord. A certain woman commonly called Jeanne the Maid has during the course of the present year been taken and captured within the boundaries and limits of our diocese. On behalf of the most illustrious prince our lord the king she has been delivered and restored to us her ordinary judge, defamed as she was by common and public report, as scandalous and suspected of many spells, incantations, invocations and conversations with evil spirits and of many other matters concerning the faith, so that we could institute proceedings against her according to the legal form customary in matters of faith. And we, desiring to proceed maturely in the said matter of

[20]

faith, according to the legal form and upon the advice and consultation of a great number of our counselors in both canon and civil law who had assembled at our instructions in this city of Rouen (of which the spiritual jurisdiction had formerly been granted us to permit us to execute and decide this matter), we judged it both necessary and fitting to have a Promoter General appointed by us in this trial, with counselors, notaries or scribes, and an usher to execute the commands and convocations necessary in the course of the trial. Be it known therefore that being desirous of following both this advice and consultation and the legal forms, having full confidence in God and being duly informed of the fidelity, integrity, intelligence, competence and personal ability of the venerable master Jean d'Estivet, priest, canon of the churches of Bayeux and Beauvais, we have constituted, created, ordained and appointed the said Jean and do hereby constitute, create, ordain and appoint him our Promoter or Procurator in everything concerning the general and particular conduct of this trial. And we give the said Promoter or Procurator by these presents license, faculty and authority to sit and appear in court and extra-judicially against the said Jeanne, to give, send, administer, produce and exhibit articles, examinations, testimonies, letters, instruments and all other forms of proof, to accuse and denounce this Jeanne, to cause and require her to be examined and interrogated, to bring the case to an end, and to exercise all acts known to be proper to the office of Promoter or Procurator, according to law and custom. Therefore, to whom it may concern, we require submission, obedience, counsel and aid towards the said Jean in the exercise of his office. In witness whereof we have affixed our seal to these present letters. Given in the house of Jean Rubé, canon of Rouen. January 9th, in the year of Our Lord 1431"

Signed: E. de Rosières.

[21]

Follows the tenor of the letter concerning the notaries

"To all those who shall see these present letters, Pierre, by divine mercy bishop of Beauvais, etc. Be it known therefore that being desirous of following both this advice and consultation and the legal forms, having full confidence in God and being duly informed of the fidelity, integrity, capacity, competence and ability of master Guillaume Colles, otherwise called Boisguillaume, and of master Guillaume Manchon, priests of the diocese of Rouen, apostolic and imperial notaries and sworn notaries of the archiepiscopal court of Rouen, and subject to the consent and approbation of the venerable vicars of the archbishopric of Rouen during the vacancy of the see, we have appointed, elected and named them, and do now appoint, elect and name them notaries or scribes in this suit. And we give them license, faculty and power to have access to the said Jeanne as often as they need to question her or hear her questioned, to receive the oaths of witnesses, to collect the confessions of Jeanne, the sayings of witnesses and the opinions of the doctors and masters, and to report them, word for word, in writing to us, to put in writing all the present and future facts of this case, to set down in writing and draw up the whole proceedings in the proper form, and in short to perform all the tasks of a notary whenever and wherever suitable. In witness whereof etc." [as above].

Follows the letter appointing a counselor

"To all those who shall see these present letters, Pierre, by divine mercy bishop of Beauvais, etc. Be it known that desirous of following both this advice and consultation and the legal forms, having full confidence in Our Lord and being duly informed of the fidelity, integrity, competence and ability

[22]

of the venerable and prudent master Jean de La Fontaine, master of arts, licentiate in decrees, we have made, ordained, charged, appointed and retained the said master Jean in the quality of counselor and examiner of the witnesses to be produced in the trial by our promoter: and we give and grant the said master Jean license, faculty and authority to receive the said witnesses, to put them on oath and examine them, to absolve them conditionally, to draw up and cause to be drawn up in writing their depositions, and to perform everything pertaining to the office of one duly appointed counselor, commissary and examiner, everything we should ourselves do if we were acting in his place. In witness whereof we have affixed our seal to these present letters. Given in the house of Jean Rubé, canon of Rouen. January 9th, in the year of Our Lord 1431."

Signed: E. de Rosières.

Follows the tenor of letters appointing the executor of our mandates

"To all those who shall see these present letters, Pierre, etc. Be it known that desirous of following both this advice and consultation and the legal forms, having full confidence in Our Lord and being duly informed of the fidelity, competence and prompt diligence of the discreet master Jean Massieu, priest, dean of the Christendom of Rouen, we have appointed, retained and ordained him executor of the mandates and convocations emanating from us in this trial: we have granted him license and by these present letters grant him all license of that office. In witness whereof we have affixed our seal to these present letters. Given in the house of Jean Rubé, canon of Rouen, 9th January in the year of Our Lord 1431."

Signed: E. De Rosières

[23]

January 13th, 1431. Reading of the evidence against Jeanne

On the following Saturday, January 13th, we the said bishop assembled in our dwelling at Rouen the following lords and masters: Gilles, abbot of Ste. Trinité de Fécamp doctor of theology; Nicolas de Venderès licentiate in canon law; William Haiton and Nicolas Couppequesne, bachelors of theology; Jean de La Fontaine, licentiate in canon law and Nicolas Loiseleur, canon of the cathedral of Rouen. In their presence we set forth all that had been accomplished in the previous session, and requested their advice upon the subsequent procedure in the case. In addition we read to them certain evidence collected both in the district where this woman was born and elsewhere, and also certain memoranda prepared upon particular points indicated earlier in the said evidence or referring to common report. When all this had been seen and heard the lords and masters decided that certain articles should be duly prepared so that the matter might appear in greater distinctness and better order, and they could more certainly decide whether there was sufficient matter for the institution of a summons and trial in matters of faith. Therefore in accordance with their advice we resolved to proceed to the preparation of such articles, and we appointed to this effect certain notable persons of especial learning in canon and civil law to assist the said notaries. And they, diligently complying with our command, proceeded to draw up the said articles on the following Sunday, Monday and Tuesday.

January 23rd, 1431. Decision concerning the preparatory information

On Tuesday, January 23rd, the following lords and masters appeared in our dwelling: master Gilles, abbot of Fécamp Nicolas de Venderès William Haiton, Nicolas Couppequesne,

[24]

Jean de La Fontaine and Nicolas Loiseleur. In their presence the articles which had been drawn up were read, and we requested their most prudent counsel upon the articles and upon the subsequent procedure. They informed us that the articles were drawn up and prepared in a good and competent form, that it was fitting to proceed to the interrogations corresponding to these articles: and declared that we the said bishop could and should proceed to draw up the preparatory information upon the acts and sayings of the prisoner. Following this advice we resolved and commanded that this preparatory information should be prepared, but since we were otherwise engaged we appointed the venerable and discreet master Jean de La Fontaine, licentiate in canon law, to conduct this inquiry.

[25]

February 13th, 1431. The officers appointed take oath

On the morning of Tuesday, February 13th of the same year there appeared before us in our dwelling the following lords and masters: Gilles, abbot of Fécamp, Jean Beaupère, Jacques de Touraine, Nicolas Midi, Pierre Maurice, Gerard Feuillet, doctors; Nicolas de Venderès and Jean de La Fontaine, licentiates in canon law; William Haiton, Nicolas Couppequesne, Thomas de Courcelles, bachelors of theology; and Nicolas Loiseleur, canon of the cathedral of Rouen. We summoned the officers already appointed and ordained by us in this suit, namely master Jean d'Estivet, the promoter; Guillaume Boisguillaume and Guillaume Manchon, notaries; master Jean Massieu, executor of our convocations and commands. We required them to take oath to fulfil their offices faithfully, and in obedience to our request they swore between our hands to fulfil and exercise them faithfully.

February 14th 15th and 16th 1431. The preparatory information is drawn up

On the Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday following, the said Jean de La Fontaine with the assistance of the two notaries proceeded to draw up the preparatory information which we had commanded.

[26]

February 19th 1431. Decision to summon the Inquisitor

On Monday, February 19th 1431, the following lords and masters appeared before us in our dwelling at eight o'clock in the morning. Gilles, abbot of Fécamp Jean Beaupère Jacques de Touraine, Nicolas Midi, Pierre Maurice, Gerard Feuillet, doctors of theology; Nicolas de Venderès, Jean de La Fontaine, licentiates in canon law; William Haiton, Nicolas Couppequesne, Thomas de Courcelles, bachelors of theology; and Nicolas Loiseleur, canon of the cathedral of Rouen. We the said bishop informed them that we had commanded a preparatory inquiry into certain articles concerning the words and deeds of this woman whom, as we had formerly said, our lord the king had surrendered and entrusted to us, to discover if there were sufficient cause to proceed against her and summon her in matters of faith. In their presence we read the articles and depositions contained in this preparatory evidence. When this had been read they were fully considered by the lords and masters in a long and mature consultation. Finally at their counsel and advice we concluded that we possessed sufficient evidence to proceed against this woman and summon her in matters of faith, and we decreed that she should be cited and summoned to reply to certain interrogations to be addressed to her. Moreover for the more convenient and salutary conduct of the matter, and in our respect for the apostolic holy see which has especially appointed lord Inquisitors of Heretical Error to correct the evils which arise against the orthodox faith, we resolved at the advice of our experienced counselors to invite and summon the lord Inquisitor of Heretics cal Error for the kingdom of France to collaborate with us in this trial if it were according to his pleasure and interest. Since however the said lord Inquisitor was then absent from the city

[27]

of Rouen, we commanded that his deputy, who was present in Rouen, should be summoned and called in his stead.

The afternoon of the same day. The Vicar of the Lord Inquisitor is summoned

The same Monday, at four in the afternoon, we were visited in our house by the venerable and discreet master Jean Le Maistre of the order of Preaching brothers, Vicar of the lord Inquisitor of the kingdom of France and appointed by him to the city and diocese of Rouen. We summoned and required the said vicar to join with us so that we might proceed in conjunction in the said matter, and we offered to acquaint him with everything which had been or should in future be done therein. Whereupon the said vicar answered that he was prepared to show us his commission or letters of appointment given him by the lord Inquisitor and according to the tenor thereof he would gladly perform all that he was in duty bound to do on behalf of the holy inquisition. Yet, since he was especially appointed for the diocese and city of Rouen only, he doubted whether his commission could be interpreted to include the present trial, although the territory had been ceded to us, because we had nevertheless undertaken these proceedings in virtue of our jurisdiction in the diocese of Beauvais. We answered that he should return to us on the next day when we should have taken counsel upon the matter.

Tuesday, February 20th 1431. The Vicar of the lord Inquisitor refuses to act

On the following Tuesday, February 20th there appeared before us in our dwelling brother Jean Le Maistre, vicar of the lord Inquisitor; master Jean Beaupère Jacques de Touraine, Nicolas Midi, Nicolas de Venderès, Pierre Maurice, Gerard Feuillet, Thomas de Courcelles, Nicolas Loiseleur, canon of

[28]

the cathedral of Rouen, and brother Martin Ladvenu, of the order of Preaching brothers. In their presence we reported that we had seen the commission or letter of appointment given to the said brother Jean Le Maistre by the lord Inquisitor, and that it was the opinion of the learned authorities to whom we had shown this letter that the said vicar could in virtue of this commission collaborate with us, that this commission included this city and the entire diocese of Rouen, and that he could conduct the present trial conjointly with us. But nevertheless to avoid the nullification of the trial we had resolved to address a summons or requisition in the form of letters patent to the lord inquisitor, requesting him to come in person to this town of Rouen and conduct the trial in person or provide a deputy authorized with more extensive and particular powers, according to the tenor of our letters transcribed below.

Whereupon the said brother Jean Le Maistre replied that for the serenity of his conscience and the safer conduct of the trial he would not participate in the present matter, unless he received especial authority. Nevertheless as far as he lawfully might he allowed that we the said bishop should proceed further until he had received more ample counsel upon the question whether he could in virtue of his commission undertake the conduct of this trial. Thus with his consent we once again offered to acquaint him with the past and future procedure. And after receiving the decisions of the assessors, we decreed in our letters of citation transcribed below, that this woman should be summoned to appear before us on the following Wednesday, February 29th.

First follows the tenor of letters of appointment of the said lean Le Maistre

"Brother Jean Graverent, of the order of Preaching brothers, professor in sacred theology, by apostolic authority Inquisitor

[29]

of Heretical Error in all the kingdom of France, to his well loved brother in Christ, Jean Le Maistre, of the same order, greeting in Our Lord Jesus Christ, the author and consummator of our faith. Heresy is a disease which creeps like a cancer, secretly killing the simple, unless the knife of the inquisitor cuts it away. Hence, with confidence in your zeal for the faith, in your discretion and integrity, and in virtue of the apostolic authority which we enjoy, we have made, created and constituted you, and by the tenor of these present letters we make, create and constitute you our vicar in the town and diocese of Rouen, giving and granting you entire authority in this town and diocese against all heretics and them suspected of heresy, their accomplices, protectors and concealers, to investigate, cite, summon, excommunicate, apprehend, detain, correct and proceed against them by all opportune means, up to and including the final sentence, with absolution and the pronouncement of salutary penances, to perform and exercise in general each and every duty pertaining to the office of inquisitor by law, custom or special privilege, which we ourselves should perform if we were acting in person. Given at Rouen, August 21st in the year of Our Lord 1424."

Follows the tenor of the letter which we the said Bishop addressed to the Lord Inquisitor of Heretical Error

"Pierre, by divine mercy Bishop of Beauvais, to the venerable father master Jean Graverent, doctor of theology, Inquisitor of Heretical Error, greeting and sincere love in Christ. Our lord the King, burning with zeal for the orthodox faith and the Christian religion, has surrendered to us as ordinary judge a certain woman named Jeanne, commonly called The Maid, who, notoriously accused of many crimes against the Christian faith and religion, suspected of Heresy, was captured and apprehended in our diocese of Beauvais. The chapter of the

[30]

cathedral of Rouen, in the vacancy of the archiepiscopal see, having granted and assigned us territory in this city and diocese in which to hold this trial, we, desiring to drive out all unholy errors disseminated among the people of God, to establish the integrity of the wounded Catholic faith, and to instruct the christian people, teaching them salvation, particularly in this diocese and other parts of this most Christian realm, resolved to examine the case of this woman with all diligence and zeal, to inquire into her acts and ways concerning the Catholic faith, and, after assembling a certain number of doctors of theology and canon law, with other experienced persons, did, after great and mature consultation, begin her legal trial in this town. But as this particularly concerns your office of inquisitor, whose duty is to direct the light of truth upon the suspicions of heresy, we beg you, venerable father, require and summon you for the faith's sake to return without delay to the town of Rouen for the further conduct of the trial and to participate therein as is incumbent upon your office, according to legal form and apostolic sanctions, so that we may continue in this suit with a common sentiment and uniform procedure. And if your occupation or other reasonable cause should occasion any delay, at least entrust your authority to brother Jean Le Maistre your vicar in this city and diocese of Rouen, or to some other deputy, so that you are not charged with the grievous delay caused by your absence after so urgent a summons, to the prejudice of the faith and the scandal of the Christian people. Whatever you decide to do, please inform us of forthwith in your letters patent. Given under our seat at Rouen, February 22nd, in the year of Our Lord 1431."

Signed: G. Boisguillaume. G. Manchon

[31]

Wednesday, February 21st. The First Public Session

On Wednesday, February 21st, at eight o'clock in the morning we the said bishop repaired to the chapel royal of the castle of Rouen, where we had summoned the said woman to appear before us at that hour and day. When we were seated in tribunal there were present the reverend fathers, lords and masters: Gilles, abbot of Ste. Trinité de Fécamp Pierre, prior of Longueville-Giffard, Jean de Châtillon Jean Beaupère Jacques de Touraine, Nicolas Midi, Jean de Nibat Jacques Guesdon, Jean Le Fèvre Maurice du Quesnay, Guillaume Le Boucher, Pierre Houdenc, Pierre Maurice, Richard Prati, and Gerard Feuillet, doctors of sacred theology; Nicolas de Jumièges Guillaume de Ste. Catherine, and Guillaume de Cormeilles, abbots; Jean Garin, canon, Raoul Roussel, doctors of canon and civil law; William Haiton, Nicolas Couppequesne, Jean Le Maistre, Richard le Grouchet, Pierre Minier, Jean Pigache, Raoul Le Sauvage, bachelors of theology; Robert Le Barbier, Denis Gastinel, Jean Le Doulx, bachelors of canon and civil law; Nicolas de Venderès, Jean Basset, Jean de La Fontaine, Jean Bruillot, Aubert Morel, Jean Colombel, Laurent Du Busc, and Raoul Anguy, bachelors of canon law; André Marguerie, Jean Alespée, Geoffrey du Crotay, and Gilles Deschamps, licentiates in civil law. In their presence there were read first the letters from the king upon

[32]

the restoration and surrender of the said woman to us, then the letters from the chapter of Rouen granting us territory: the tenor of which is given below. Then master Jean d'Estivet, appointed and constituted our promoter in this trial, reported that he had caused the said Jeanne to be cited and summoned by our usher to appear at the said place, on the day and hour prescribed, to answer the questions which should legally be put to her, as is clearly shown in the report of the usher affixed to our letters of citation.

Follows the tenor of the letters of citation and writ

"Pierre, by divine mercy bishop of Beauvais, being in possession of territory in the city and diocese of Rouen, by the authority of the venerable chapter of the cathedral of Rouen in the vacancy of the archiepiscopal see, for the purpose of undertaking and concluding the aforementioned matter, to the dean of the Christendom of Rouen, to all priests, whether curates or not, of this city and diocese, who shall see these present letters, greeting in the author and consummator of our faith. Since a woman commonly called Jeanne the Maid had been captured and apprehended within our diocese of Beauvais, and had been surrendered, dispatched, given and delivered to us by the most Christian and serene prince the lord King of France and England as a person vehemently suspected of heresy, so that we should institute proceedings against her in matters of faith in view of the fact that rumors of her acts and sayings wounding our faith had notoriously spread not only through the kingdom of France, but also through all christendom, we, desirous of proceeding maturely in the affairs, resolved, after a diligent inquiry and consultation with learned men, that the said Jeanne should be summoned, cited, and heard upon the articles and interrogations given and made against her, and upon things concerning the faith. Hence we

[33]

require each and every one of you not to wait for another if he is summoned by us nor to excuse himself by another. Therefore peremptorily summon the said Jeanne so vehemently suspected of heresy to appear before us in the chapel royal of the castle of Rouen at eight o'clock in the morning of Wednesday, February 21St, to speak the truth upon the said articles, interrogations and other matters of which we esteem her suspect, and to be dealt with as we shall think just and reasonable, intimating to her that she will be excommunicated if she fails to appear before us on that day. Give us a faithful account thereof in writing, you who are to be present to follow it. Given at Rouen under our seal Tuesday, February 20th 1431."

Signed: G. Boisguillaume. G. Manchon

The Usher's writ

"To the reverend father in Christ, the lord Pierre by divine mercy bishop of Beauvais, possessing territory in the city and diocese of Rouen by the pleasure of the venerable chapter of the cathedral of Rouen in the vacancy of the archiepiscopal see for the purpose of undertaking and concluding the aforementioned matter, your humble Jean Massieu, priest, dean of the Christendom of Rouen, prompt obedience to your orders in all reverence and honor. Be it known to you, reverend father, that in virtue of the summons you addressed to me, to which this present writ is joined, I have peremptorily cited to appear before you at eight o'clock in the morning of Wednesday, February 21st, in the chapel royal of the castle of Rouen, the woman commonly called The Maid, whom I have apprehended in person in the limits of this castle, and whom you vehemently suspect of heresy, to answer truthfully to the articles and interrogations which shall be addressed to her upon matters of faith and other points on which you deem her

[34]

[PAGE 35: NOT AVAILABLE -- GRAPHIC]

suspect, and to be dealt with according to law and reason and the intimation of your letters. The said Jeanne replied that she would willingly appear before you and answer the truth to the interrogations to which she shall be subjected; that, nevertheless, she requested you to summon in this suit ecclesiastics of the French side equal in number to those of the English party and, further, she humbly begged you, reverend father, to permit her to hear Mass before she appears before you, and to inform you of these requests, which I have done. By these present letters sealed with my seal and signed with my sign manual, I testify to you, reverend father, that all the foregoing has been done by me. Given in the year of Our Lord, 11431, On Tuesday preceding the said Wednesday.

Signed: Jean.

The Petition of the Promoter. Decision forbidding Jeanne to attend divine offices

After the reading of these letters the aforesaid promoter urgently required this woman to be commanded to appear in judgment before us in accordance with the summons, to be examined upon certain articles concerning the faith; which we granted. But since in the meantime this woman had requested to be allowed to hear Mass, we informed the assessors that we had consulted with notable lords and masters on this question, and in view of the crimes of which this woman was defamed, especially the impropriety of the garments to which she clung, it was their opinion that we should properly defer permission for her to hear Mass and attend the divine offices.

Jeanne is led in to judgment

Whilst we were saying these things this woman was brought in by our usher. Since she was appearing in judgment before us we began to explain how this Jeanne had been taken and

[36]

apprehended within the boundaries and limits of our diocese of Beauvais; how many of her actions, not in our diocese alone but in many other regions also, had injured the orthodox faith, and how common report of them had spread through all the realms of Christendom; how recently the most serene and Christian prince our lord the king had given and delivered this woman to us to be tried in matters of faith according to law and reason. Therefore, considering the public rumor and common report and also certain information already mentioned, after mature consultation with men learned in canon and civil law, we decreed that the said Jeanne should be summoned and cited by letter to answer the interrogations in matters of faith and other points truthfully according to law and reason, as set forth in the letters shown by the promoter.

First exhortation to Jeanne

As it is our office to keep and exalt the Catholic faith, we did first, with the gentle succor of Jesus Christ (whose issue this is), charitably admonish and require the said Jeanne, then seated before us, that to the quicker ending of the present trial and the unburdening of her own conscience, she should answer the whole truth to the questions put to her upon these matters of faith, eschewing subterfuge and shift which hinder truthful confession.

She is required to take oath

Moreover, according to our office, we lawfully required the said Jeanne to take proper oath, with her hands on the holy gospels, to speak the truth in answer to such questions put to her, as beforesaid.

The said Jeanne replied in this manner: I do not know what you wish to examine me on. Perhaps you might ask such things that I would not tell." Whereupon we said: "Will you

[37]

swear to speak the truth upon those things which are asked you concerning the faith, which you know?" She replied that concerning her father and her mother and what she had done since she had taken the road to France, she would gladly swear; but concerning the revelations from God, these she had never told or revealed to any one, save only to Charles whom she called King; nor would she reveal them to save her head; for she had them in visions or in her secret counsel; and within a week she would know certainly whether she might reveal them.

Thereupon, and repeatedly, we, the aforementioned bishop, admonished and required her to take an oath to speak the truth in those things which concerned our faith. The said Jeanne, kneeling, and with her two hands upon the book, namely the missal, swore to answer truthfully whatever should be asked her, which she knew, concerning matters of faith, and was silent with regard to the said condition, that she would not tell or reveal to any person the revelations made to her.

First Inquiry after the oath

When she had thus taken the oath the said Jeanne was questioned by us about her name and her surname. To which she replied that in her own country she was called Jeannette, and after she came to France, she was called Jeanne. Of her surname she said she knew nothing. Consequently she was questioned about the district from which she came. She replied she was born in the village of Domrémy, which is one with the village of Greux; and in Greux is the principal church.

Asked about the name of her father and mother, she replied that her father's name was Jacques d'Arc, and her mother's Isabelle.

[38]

Asked where she was baptized, she replied it was in the church of Domrémy.

Asked who were her godfathers and godmothers, she said one of her godmothers was named Agnes, another Jeanne, another Sibylle; of her godfathers, one was named Jean Lingué, another Jean Barrey: she had several other godmothers, she had heard her mother say.

Asked what priest had baptized her, she replied that it was master Jean Minet, as far as she knew.

Asked if he was still living, she said she believed he was.

Asked how old she was, she replied she thought nineteen. She said moreover that her mother taught her the Paternoster, Ave Maria and Credo; and that no one but her mother had taught her her Credo.

Asked by us to say her Paternoster, she replied that if we would hear her in confession then she would gladly say it for us. And as we repeatedly demanded that she should repeat it, she replied she would not say her Paternoster unless we would hear her in confession. Then we told her that we would gladly send one or two notable men, speaking the French tongue, to hear her say her Paternoster, etc.; to which Jeanne replied that she would not say it to them, except in confession.

Prohibition against her leaving prison

Whereupon we, the aforementioned bishop, forbade Jeanne to leave the prison assigned to her in the castle of Rouen without our authorization under penalty of conviction of the crime of heresy. She answered that she did not accept this prohibition, adding that if she escaped, none could accuse her of breaking or violating her oath, since she had given her oath to none. Then she complained that she was imprisoned with chains and bonds of iron. We told her that she had tried elsewhere and on several occasions to escape from prison, and

[39]