JOAN OF ARC The Warrior Maid

Chapter 24

Jeanne’s Last Field

“I fear naught but treachery.”

Jeanne’s own words.

“Saith each to other, ‘Be near me still;

We will die together, if God so will.’”

John O’Hagan. “The Song of Roland.”

No longer buoyed up by hope Jeanne began to feel her

wound to faintness, and was compelled to seek her

room for rest. As she lay on her bed, despondent and

heavy-hearted, her Saints came to her with words of comfort.

Daily they appeared, but since the crowning of Charles at

Reims they had given the maiden no specific direction. There

had been no further definite message. They had said, “Raise

the siege of Orléans and lead the Dauphin to his crowning”;

and she had done both things. Now they consoled the girl in

her humiliation and sorrow, and uttered a message:

“Remain at St. Denys, Daughter of God,” they said. “Remain

at St. Denys.”

And Jeanne resolved to do so, but this was not allowed.

After a few days Charles announced his intention of returning

to the Loire, and ordered the army to make ready for

the march. And now the cause of the shameful treason at

Paris was learned. There was a new treaty with Burgundy.

Charles had signed it just before coming to St. Denys. La

Trémouille and his party had triumphed, and an inglorious

armistice which was to last until Christmas was the result.

The position of the Favorite was becoming precarious under

the great national feeling that was beginning to sweep the land,

and his only safety from his foes was to keep his hold upon

Charles. To this end the King was persuaded to consent to

the abandonment of the campaign. Charles was not difficult

to win over, for by so doing he would be left in peace to pursue

his pleasures, and La Trémouille would be free to misrule

France as he liked.

The truce covered the whole of the country north of the

Seine from Nogent, sixty miles above Paris, to the sea. While

it lasted Charles might not receive the submission of any city

or town, however desirous it might be to acknowledge him,

although strangely enough he might attack Paris, while equally

as strange, Burgundy might assist the Regent to defend it

against him. Compiègne was to be given as hostage to Burgundy.

The French hoped by giving him this city that he

might be drawn from the English alliance.

Compiègne, however, refused to be given, thereby showing

more loyalty to the cause of France than did the poor stick of a

King. Burgundy entered into the truce for his own purposes,

playing France against England to increase his power at

French expense. Philip was justified in seeking a truce, for

many towns which had been Burgundian had thrown off such

allegiance, and turned to Charles. He wished to prevent such

desertions for the future. England might come into this peace

at any time if she wished. This left England free to wage war

against France, and the French could move against the English,

but not if any stronghold was held for the English by the

Burgundians. It is difficult to see what France hoped to

gain by such an armistice, though there were those among

the Councillors who sincerely believed that from the arrangement

a lasting peace might result both with Burgundy and the

English. Later it was learned how Burgundy had beguiled

them. Alençon and the captains denounced the truce bitterly.

“If the King had taken Paris, he could have made his own

terms with Philip,” the young duke told Jeanne.

“The noble King is deceived,” said the girl sorrowfully.

“There will be no peace with Burgundy for six years, and not

until seven are sped shall the King enter his capital.”

“Jeanne, do you in truth know that?” questioned the young

man quickly. “You speak as though you do.”

“I do know, gentle duke. My Voices have told me. Paris

would have been ours had we but persisted in the attack, and

in a few months northern France would have been clear of the

English. Now it will take twenty years to drive them out.”

“Twenty years,” repeated Alençon aghast. “Have your

voices told you that also, Jeanne?”

“Yes, fair duke. And the pity of it! Oh, the pity of it!”

“The pity of it,” he echoed. “For now we must start for

the Loire, leaving all these cities and towns that have made

submission to Charles to the mercies of the Regent. They

have written piteous letters to the King, entreating him not to

abandon them, but he consoles them by telling them that he is

withdrawing because he does not wish to strip the country to

feed the army; yet the English are left free to harry the towns,

and their state will be worse than before they made submission.

We should not leave.”

“I shall not go,” returned Jeanne quietly. “My Voices have

told me to remain at St. Denys. I shall obey them.”

She reckoned without her host. When the King was ready

to march he commanded her attendance. She refused to go.

She had never disobeyed her Heavenly Guides, she told him, so

she gave the King her duty, and begged of him to let her stay.

Charles was not minded to do this, so he ordered that she be

brought along. Jeanne’s wound was not yet healed, and she

was scarcely able to get about. So the helpless maiden was

forced against her will to go with the King.

It was a dreary march back to Gien, but it was made quickly.

So eager was the King to return to his amusements that the

one hundred and fifty miles’ distance from St. Denys to Gien

was traversed in eight days. When the city was reached

Charles disbanded the army; so that of all the great number

of men who had set forth from the place three months agone

with banners flying nothing remained but the men of the King’s

body guard. Some were free lances from many lands, but

for the most part they were French gentlemen who had served

without pay for the love of France and the Maid. Jeanne took

farewell of them with sadness: the brave Dunois, the bold La

Hire, Poton Zaintrailles, Boussac, Culent, and others. The

great army was never mustered again.

Normandy, being an English possession, was exempt from

the truce, so Alençon prayed permission to lead troops against

the English strongholds there, wishing also to take the Maid

with him. “For many,” he said, “would come with them for

her sake who would not budge without her.”

But neither the King nor La Trémouille would grant the

grace. They did not wish the ardent young prince to become

a leader of the French against the enemy, and the Maid had

become too much of a power to be lost sight of. So firmly and

decidedly the project was dismissed, and he was relieved of his

command. In disgust the young duke retired to his estates.

He and Jeanne had grown to be great friends. He believed

in her implicitly, and she was fond of him that he did so believe;

and also because of his nobility of character, and his connection

with the house of Orléans. It was the last time that

they ever met. “And thus was broken the spirit of the Maid,

and of the army.”[23]

Jeanne pined in the days that followed; for the Court drifted

from castle to castle and from town to town in search of amusement.

Its frivolity and idle merrymaking were not to her liking,

but she was forced to follow in its train. She had her own

Household, to which were now added women and maidens of

rank, and everything which could show that she was one whom

the King delighted to honor. The Queen came up from

Bourges, and gave her a warm welcome. Rich apparel, gorgeous

in coloring, was bestowed upon her, and, be it said to the

credit of Charles, she was not stinted for money. The King

was not ungrateful. He knew that it was almost impossible

to estimate the moral effects of Jeanne’s victories about Orléans

and upon the Loire. All Europe was filled with wonder,

and sent eagerly to him for news of her. All this he knew,

but he misjudged the girl, and tried to pay his debt to her by

showering gifts upon her when she wanted only to fight for

France. Pretty clothes and a life of ease might satisfy other

girls, but not Jeanne D’Arc, who lived only for the welfare

of the country. Had Charles but availed himself of her influence,

the splendid confidence of his soldiers, and the loyalty

of the country people, treating with Burgundy after taking

Paris, it is more than likely that the English power in France

would have been broken in 1429 as quickly as it was twenty

years later.

There was one who recognized Jeanne’s services to the

French to the full: the English Regent, Bedford. Writing

to England four years later he acknowledged that the gains

France had made against England were due mainly to the

“panic caused by the Maid, and the encouragement given by her

to the French.” Had Bedford been King of France he would

have known how to use such a power.

The leaders did not mind if Jeanne worked, but they were not

desirous that there should be more individual triumphs. It

threw their own treachery to the realm into strong relief, and

made for their downfall. On the upper Loire were several

strongholds which did not come under the truce with Burgundy,

and these might be proceeded against with impunity. The

strong town of La Charité was held by Perrinet Gressart, who

had begun life as a mason but, war being the best trade, made

a fine living out of the rich district of the upper Loire. He

was in a measure under Philip of Burgundy, but when the

duke pressed him too hard he threatened to sell out to the

enemy, so that he was left in peace to pillage to his heart’s content.

Early in his career this soldier of fortune had seized La

Trémouille as he was passing through the Burgundian country,

and the rich favorite was allowed to proceed on his journey

only at the price of a month’s captivity and a heavy ransom.

The little town of St. Pierre le Moustier, which stood about

thirty-five miles above La Charité, was held by a Spanish Free

Lance who had married a niece of Gressart. Its garrison

waged a war of wastry, pillaging the peasants and the country

far and wide, and holding all whom they could take to ransom.

It was decided to launch an expedition against these strongholds

under Jeanne. If they fell it would satisfy the grudge

that La Trémouille held for his captivity; if they did not fall

there would be further loss of Jeanne’s influence, and the favorite

would be rid of a danger that was threatening his control

of France.

Jeanne preferred to go against Paris, but the capital was

at this time under the government of Burgundy, who had been

appointed lieutenant by Bedford, and therefore was within the

truce. So, glad of any sort of a dash against the enemy,

Jeanne went to Bourges to muster the men. The force was

to be under d’Albret, a son-in-law of La Trémouille, a man not

inclined to be friendly to the Maid. By the end of October

all was in readiness, and it was decided to go against St. Pierre

le Moustier before marching against La Charité. It was a

strong little town with fosses, towers, and high walls some two

miles east of the River Allier, overlooking the fields which lay

between the walls and the river.

The town was plied by the artillery for several days, and

after a breach was made Jeanne ordered an assault, herself

leading with standard in hand. The men rushed to the walls,

but were driven back; the retreat sounded, and the troops were

retiring from the point of attack when Jean D’Aulon, Jeanne’s

squire, being himself wounded in the heel and unable to stand

or walk, saw the Maid standing almost alone near the walls.

He dragged himself up as well as he could upon his horse, and

galloped up to her, crying:

“What are you doing here alone, Pucelle? Why do you not

retreat with the others?”

“Alone?” questioned Jeanne, raising the visor of her helmet

and gazing at him with glowing eyes. “I am not alone. Fifty

thousand of my people are about me. I will not leave until

this town is mine.”

The squire looked about him in bewilderment, for there were

not more than five men of her Household near her, yet there

she stood waving her standard while the arrows and bolts from

the town rained and whistled about her.

“You are mistaken, Jeanne,” he said. “I see not such a

host. Come away, I beseech you. The troops are in full retreat.”

“Look after the screens and faggots,” ordered the Maid.

Mystified, the worthy man did as he was bid, while the clear

voice rang out the command:

“To the bridge, every man of you.”

Back came the men on the run with planks and faggots, and

so filling the moat returned to the assault, and the town was

taken. D’Aulon watched the onslaught in wonder.

“The deed is divine,” he exclaimed in amazement. “Truly

the will and the guidance of our Lord are with her, else how

could so young a maid accomplish such a marvel.”

The town was taken, and the soldiers would have pillaged

even the churches, but Jeanne, remembering Jargeau, firmly

forbade it, and nothing was stolen.

Then the Maid and d’Albret proceeded to Moulins, an important

town further up the river in the Bourbonnais, whence

they sent letters to the loyal towns requiring munitions for

the attack on La Charité. It was to the interest of the neighboring

towns that this place should be cleared away, for the

garrison was a plague to the surrounding country, but only a

few of them responded to the appeal for money and supplies.

Orléans, generous as always, sent money, gunners, artillery and

warm clothing, but the army was ill-equipped for the siege.

Jeanne moved her forces before the strong town and settled

down for the siege, but the King neither forwarded money nor

supplies. Riom promised money, but that was the end of it.

Left without the munitions necessary, her army ill-fed, ill-clothed

against the bitter November weather, Jeanne wrote

to the citizens of Bourges an urgent appeal. “The troops must

have help,” she said, “else the siege must be abandoned, which

would be a great misfortune to your city and to all the country

of Berri.”

Bourges voted to send the money, but it was never received.

Vigorously the troops pummelled the strong town with what

artillery they had, but a siege can not be prosecuted without

provisions and other supplies, and the King left them to get

along without any support. The men naturally became discontented.

A month was wasted in artillery play, and an assault

resulted only in loss of men. In great displeasure Jeanne

raised the siege. She could inspire men to fight as they never

fought before, but she could not work miracles. God would

give the victory to those who helped themselves. Hungry,

cold, disheartened troops could not fight without munitions and

provisions. So they were disbanded, and retreated from the

town, leaving some of their artillery on the field.

Thus ended the fighting for the year 1429, and sadly the

Maid returned to the Court. In spite of unbelief and opposition

she had accomplished incredible deeds since her setting

forth from Vaucouleurs, and would have done them again had

she not been hampered by the King and his Council.

Charles was at his beautiful Château at Méhun-sur-Yèvre,

where Jeanne joined him. She was overcast and sorrowful at

the failure of the siege of La Charité. She had wished to go

into the Isle of France to help the people of the loyal towns

there, whose state was pitiful, but had been sent on the unsuccessful

expedition instead. Invaders and robbers alike were

made bold by the withdrawal of Charles from northern France;

and the English were active, forcing exile or death on the defenseless

people, who would not forswear their loyalty. Many

villages were forsaken, the inhabitants having been driven into

other parts of France. There was pestilence and famine everywhere.

In Paris wolves prowled openly, and its citizens died

orchards, and vineyards and towered fortresses, had been abandoned

by the English and Burgundians to its own protection;

Burgundy going to look after his personal concerns, while Bedford

swept the adjacent country with fire and sword. She had

been needed in northern France, and Jeanne’s heart was heavy

with tenderness for the suffering people of that region.

Many feasts were held in her honour, and both the King

and the Queen showered attentions upon her, trying by fine

clothes and caresses to make her forget her mission and her

despair. In December the King, in the presence of La

Trémouille, Le Macon, and other courtiers, conferred upon

Jeanne a patent of nobility, sealed with a great seal of green

wax upon ribbons of green and crimson, the Orléans colours.

“In consideration of the praiseworthy and useful services

which she has rendered to the realm and which she may still

render, and to the end that the divine glory and the memory

of such favors may endure and increase to all time, we bestow

upon our beloved Jehanne d’Ay[24] the name of Du Lys in

acknowledgment of the blows which she had struck for the lilies

of France. And all her kith and kin herewith, her father,

mother, brothers and their descendants in the male and female

line to the farthest generation are also ennobled with her, and

shall also bear the name Du Lys, and shall have for their

arms a shield azure with a sword supporting the crown and

golden fleur-de-lis on either side.” Charles was a “well languaged

prince,” and he conferred the patent with fine and

noble words, but Jeanne would far rather have had a company

of men to lead into the suffering country of northern France.

She cared nothing for either the grant of nobility or the blazon,

and never used them, preferring to be known simply as Jeanne

the Maid. Her brothers, however, Pierre and Jean, were delighted,

and ever after bore the name of Du Lys.

The winter passed, bringing with it Jeanne’s eighteenth

birthday. The truce with Burgundy had been extended until

Easter, and the Maid waited the festival with what grace she

could, determined that the end of the truce should find her

near Paris. March found her at Sully, where the Court was

visiting at La Trémouille. Easter was early that year, falling

on March twenty-seventh, and as soon as it was over Jeanne left

the Court, and rode northward with her Company.

On her way north she heard of the disaffection of Melun, a

town some twenty-one miles south of Paris, which had been

in English hands for ten years. When the English took the

place they had locked up its brave captain, Barbazon, in

Louvier, from which place he had recently been released by La

Hire. In the Autumn of 1429 Bedford had turned the town

over to Burgundy; but during April on the return of Barbazon

the burghers rose, and turned out the captain and his Burgundian

garrison, and declared for France. It was a three

days’ ride from Sully-sur-Loire to Melun across rough country

and up the long ridge of Fontainebleau forest, but Jeanne

arrived with her men in time to help the citizens resist the onset

made against the town by a company of English which had

been sent to restore the English allegiance. Joyfully they

welcomed her, giving over the defense into her charge.

The first thing that Jeanne did was to make a survey of the

walls, that she might consider their strength and how best to

fortify them against assault. One warm pleasant day in April

she stood on the ramparts superintending some repairs that

she had ordered when all at once her Voices came to her.

“Daughter of God,” they said, “you will be taken before the

Feast of St. Jean. So it must be. Fear not, but accept it

with resignation. God will aid you.”

Jeanne stood transfixed as she heard the words. The feast

of St. Jean was near the end of June. Only two months more

in which to fight for France. Her face grew white as the words

were repeated, and a great fear fell upon her. A prisoner?

Better, far better would it be to die than to be a prisoner in the

hands of the English. All their taunts, their gibes, their

threats came to her in a rush of memory. She knew what to

expect; the stake and the fire had been held up as a menace

often enough. Terrified, the young girl fell on her knees,

uttering a broken cry of appeal:

“Not that! Not that! Out of your grace I beseech you

that I may die in that hour.”

“Fear not; so it must be,” came the reply. “Be of good

courage. God will aid you.”

“Tell me the hour, and the day,” she pleaded brokenly.

“Before the St. Jean. Before the St. Jean,” came the reply.

And that was all.

For a long moment Jeanne knelt, her face bowed upon her

hands; then she bent and kissed the ground before her.

“God’s Will be done,” she said. Rising she went on with

her work, as calmly, as serenely as though knowledge of her

fate had not been vouchsafed her.

She knew, but she did not falter. A braver deed was never

done. Who else has shown such courage and high heart since

the beginning of the world? To know that she was to be taken,

and yet to proceed with her task as though she knew it not!

There is an ecstasy in the whirl of battle; a wild joy in the mad

charge of cavalry and the clash of steel on steel. There is

contagion in numbers filled with the thought that the enemy

must be overcome, the fortress taken; a contagion that leads to

deeds of valour. There is inspiration in the call of the bugle,

or sound of the trumpet, in the waving of banners, in the war

cries of the captains. But for the prisoner there is no ecstasy,

no joy, no valorous contagion induced by numbers, no inspiration

of music, or banners, or war cries. There are only the

chill of the dungeon, the clank of the chain, the friendless loneliness,

and at length the awful death. But with capture certain,

with the consciousness of what was in store, this girl of

eighteen went her way doing all that she could in the little time

that was left her for France.

The fighting of the Spring was to be along the River Oise.

While Charles and his Council had rested serenely reliant upon

the faith of Burgundy, the duke and the Regent had completed

their plans for the Spring campaign. An army, victualled in

Normandy and Picardy, was to take the towns near Paris and

thereby relieve the city, which was to be well garrisoned. Only

by recovering these towns from the French could Paris be made

secure. The good town of Compiègne was especially to be desired,

for whosoever held Compiègne would come in time to

hold Paris. It was thirty leagues to the north and west of the

capital, lying on the River Oise. It will be recalled that

Charles had offered the city as a bribe to Burgundy to woo

him from the English allegiance, but the city had refused to be

lent. It had submitted to the King and the Maid the August

before, and its people remained loyal, declaring that they would

die and see their wives and children dead before they would

yield to England or Burgundy; saying that they preferred

death to dishonour. They had imbibed Jeanne’s spirit, and

the Maid loved them.

It was further planned by the Regent to clear the road to

Reims so that young Henry of England might be crowned

there. Bedford was bringing him over from England for that

purpose, believing that the French would be more inclined to

support him if he were crowned at Reims. This plan was

given up, however, for Burgundy warned Bedford against attempting

to imitate the feat of the Maid, saying that it was too

difficult. So the real objective of the spring campaign became

Compiègne, other movements being to relieve Paris, and

to distract the French on their rear. For the French were

rising; rising without their King. All over northern France

there were stir and activity as troops began to gather to go

against the enemy.

From Melun Jeanne journeyed to Lagny, which was but a

short distance away, but the road was through a country full

of enemies, in which she was subject to attack from every direction.

It was one of the towns recovered for France the August

before, and was now held for Ambrose de Loré by Foucault

with a garrison of Scots under Kennedy, and a Lombard soldier

of fortune, Baretta, with his company of men-at-arms, cross-bowmen

and archers. It was making “good war on the English

in Paris,” and “choking the heart of the kingdom.”

Paris itself became greatly excited when it heard of the

arrival of the Maid at Lagny, its ill-neighbor, and feared that

she was coming to renew her attack on the city. Among the

English also there was consternation when the tidings spread

that again Jeanne had taken to the field. “The witch is out

again,” they declared to their captains when the officers sought

to embark troops for France, and many refused to go. They

deserted in crowds. Beating and imprisonment had no effect

upon them, and only those who could not escape were forced

on board.

Jeanne had scarcely reached Lagny when news came that a

band of Anglo-Burgundians was traversing the Isle of France,

under one Franquet d’Arras, burning and pillaging the country,

damaging it as much as they could. The Maid, with Foucault,

Kennedy and Baretta, determined to go against the freebooters.

They came up with the raiders when they were laying siege

to a castle, and were laden with the spoils of a recently sacked

village. The assault was made, and “hard work the French

had of it,” for the enemy was superior in numbers. But after

a “bloody fight” they were all taken or slain, with losses also

to the French in killed and wounded.

For some reason the leader, Franquet d’Arras, was given to

Jeanne. There had been an Armagnac plot in Paris in March

to deliver the city to the loyalists, but it had failed. The Maid

hoped to exchange the leader of the freebooters for one of the

chief conspirators who had been imprisoned, but it was found

that the man had died in prison, so the burghers demanded

Franquet of Jeanne, claiming that he should be tried as a murderer

and thief by the civil law. Jeanne did as requested,

saying as she released him to the Bailly of Senlis:

“As my man is dead, do with the other what you should do

for justice.”

Franquet’s trial lasted two weeks; he confessed to the charges

against him, and was executed. The Burgundians although

accustomed to robbery, murder and treachery, charged Jeanne

with being guilty of his death, and later this was made a great

point against her.

There was another happening at Lagny that was later made

the basis of a charge against the Maid. A babe about three

days old died, and so short a time had it lived that it had not

received the rites of baptism, and must needs therefore be

buried in unconsecrated ground. In accordance with the custom

in such cases the child was placed upon the altar in the

hope of a miracle, and the parents came to Jeanne requesting

her to join with the maidens of the town who were assembled

in the church praying God to restore life that the little one

might be baptized.

Jeanne neither worked, nor professed to work miracles.

She did not pretend to heal people by touching them with her

ring, nor did the people attribute miracles to her. But she

joined the praying girls in the church, and entreated Heaven

to restore the infant to life, if only for so brief a space of time

as might allow it to be received into the Church. Now as they

knelt and prayed the little one seemed suddenly to move. It

gasped three times and its color began to come back.

Crying, “A miracle! A miracle!” the maidens ran for the

priest, and brought him. When he came to the side of the child

he saw that it was indeed alive, and straightway baptized it and

received it into the Church. And as soon as this had been

done the little life that had flared up so suddenly went out,

and the infant was buried in holy ground. If receiving an

answer to earnest prayer be witchcraft were not the maidens

of Lagny equally guilty with Jeanne? But this act was later

included in the list of charges brought against her.

From Lagny Jeanne went to various other places in danger,

or that needed encouragement or help. She made two hurried

visits to Compiègne which was being menaced in more than one

direction by both parties of the enemy, and was now at Soissons,

now at Senlis, and presently in the latter part of May came to

Crépy-en-Valois.

And here came the news that Compiègne was being invested

on all sides, and that preparations to press the siege were being

actively made. Eager to go at once to the aid of the place

Jeanne ordered her men to get ready for the march. She had

but few in her company, not more than two or three hundred,

and some of them told her that they were too few to pass

through the hosts of the enemy. A warning of this sort never

had any effect upon Jeanne.

“By my staff, we are enough,” she cried. “I will go to see

my good friends at Compiègne.”[25]

At midnight of the twenty-second, therefore, she set forth

from Crépy, and by hard riding arrived at Compiègne in the

early dawn, to the great joy and surprise of the Governor,

Guillaume de Flavy, and the people who set the bells to ringing

and the trumpets to sounding a glad welcome.

The men-at-arms were weary with the night’s ride, but

Jeanne, after going to mass, met with the Governor to arrange

a plan of action.

Now Compiègne in situation was very like to Orléans, in

that it lay on a river, but it was on the south instead of the

north bank. Behind the city to the southward stretched the

great forest of Pierrefonds, and at its feet was the River Oise.

In front of the city across the river a broad meadow extended

to the low hills of Picardy. It was low land, subject to floods,

so that there was a raised road or causeway from the bridge

of Compiègne to the foot of the hills, a mile distant. Three

villages lay on this bank: at the end of the causeway was the

tower and village of Margny, where was a camp of Burgundians;

on the left, a mile and a half below the causeway, was

Venette, where the English lay encamped; and to the right, a

league distant above the causeway, stood Clairoix, where the

Burgundians had another camp. The first defence of the city,

facing the enemy, was a bridge fortified with a tower and boulevard,

which were in turn guarded by a deep fosse.

It was Jeanne’s plan to make a sally in the late afternoon

when an attack would not be expected, against Margny, which

lay at the other end of the raised road. Margny taken, she

would turn to the right and strike at Clairoix, the second Burgundian

camp, and so cut off the Burgundians from their

English allies at Venette. De Flavy agreed to the sortie, and

proposed to line the ramparts of the boulevard with culverins,

men, archers, and cross-bowmen to keep the English troops

from coming up from below and seizing the causeway and

cutting off retreat should Jeanne have to make one; and to

station a number of small boats filled with archers along the

further bank of the river to shoot at the enemy if the troops

should be driven back, and for the rescue of such as could not

win back to the boulevard.

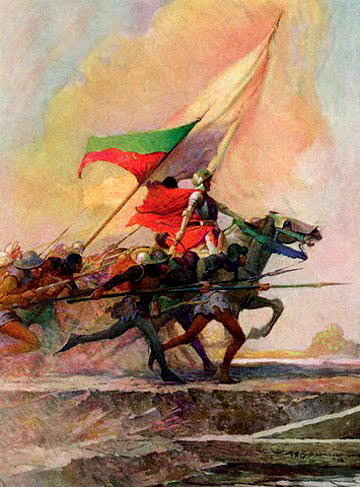

“FORWARD! THEY ARE OURS!”

“FORWARD! THEY ARE OURS!”

The whole of the long May day was occupied in completing

arrangements, and it was not until five o’clock in the afternoon

that everything was in readiness. It had been a beautiful

day, warm with May sunshine, but cooled by a breeze from the

west, sweet with the scent of flowers and growing grass. The

walls of the city, the windows and roofs of the houses, the

buildings on the bridge, and the streets were lined with people

waiting to see the Maid and her companions set forth. Presently

Jeanne appeared, standard in hand, mounted on a great

grey horse, and clad in a rich hucque of crimson cramoisie over

her armour. At sight of her the people went wild with joy,

shouting:

“Noël! Noël! Noël!” while women and girls threw flowers

before her. Jeanne turned a happy face toward them,

bowing and smiling, as she rode forth to her last field.

With her rode D’Aulon, his brother, Pothon le Bourgnignon,

her brothers, Jean and Pierre, and her Confessor, Father

Pasquerel, and a company of five hundred men. Across the

bridge they clattered, then took at speed the long line of the

causeway to Margny.

“Forward! they are ours!” called Jeanne’s clear voice as the

village was reached.

With a shout the troops hurled themselves upon the Burgundians,

taking the enemy completely by surprise. A scene of

confusion ensued. There were cries of triumph from the

French as they chased the Burgundians hither and thither, and

cries of dismay and clashing of steel from the Burgundians as

they scattered before the French through the village. Everything

was going as the Maid had planned; for the town was

taken.

Just at this juncture Jean de Luxembourg, commander of

the Burgundian camp at Clairoix, with several companions, was

riding from Clairoix on a visit to the commander at Margny.

They had drawn rein on the cliff above Margny, and were discussing

the defences of Compiègne when, hearing the clash of

arms, they looked over the bluff and saw the scrimmage.

Wheeling, they made for Clairoix, and brought up their troops

on a gallop. To render the post of Margny untenable took

time; so when, flushed with triumph, Jeanne’s men turned into

the plain toward Clairoix, Luxembourg’s men-at-arms set upon

them, attacking their right flank. The French rolled back,

overwhelmed by the onslaught. Rallying her men, Jeanne

charged, and swept back the enemy. Again the French were

repulsed; again the Maid drove back the Burgundians; and

thus the fray raged on the flat ground of the meadow, first in

favor of the one, and then of the other. As they surged with

this alternative of advance and retreat the French were pressed

back to the causeway. And then, as reinforcements of the Burgundians

continued to arrive a panic suddenly seized the

French, and they broke and ran for the bridge and the boats.

In vain Jeanne tried to rally them to the charge. For once

they were deaf to her voice.

Caring only for the safety of her band Jeanne covered the

rear, charging the enemy with those who remained with her,

with such effect that they were driven back full half the length

of the causeway. “She that was the chief and most valiant of

her band, doing deeds beyond the nature of woman.”[26]

Suddenly there sounded a loud hurrah, and from a little wood

on the left there came galloping and running across the meadow

land from Venette the men-at-arms and the archers of England.

Assailed on all sides, for the Burgundians at Margny had rallied

and re-entered the fray, the confusion of the French became

extreme. A struggling, seething mass of fugitives

crowded the causeway, running for their lives. Men and foot

soldiers, and behind them mounted men-at-arms, spurring hard,

and all making for the boulevard. The gunners on the walls

trained their cannon on the mass of men, but fugitives and

enemy were so commingled that friend and foe could not be distinguished,

and they dared not fire. And De Flavy did

nothing.

Roused to the danger of their position D’Aulon entreated

Jeanne to make for the town.

“The day is lost, Pucelle,” he cried. “All are in retreat.

Make for the town.” But Jeanne shook her head.

“Never,” she cried. “To the charge!”

D’Aulon, Jean and Pierre, her brothers, all her own little

company, closed around her, resolved to sell their lives dearly

in her defence, and D’Aulon and Pierre, seizing hold of her

bridle rein, forcibly turned her toward the town, carrying her

back in spite of herself.

But now they were assailed from all sides, the little company

fighting, struggling, contesting every inch of ground, beating

off their adversaries, and advancing little by little toward the

boulevard.

“We shall make it, Jeanne,” exulted Pierre D’Arc when they

were within a stone’s throw of the walls, but the words died

on his lips, for at this moment came a ringing order from the

gate:

“Up drawbridge: close gates: down portcullis!”

Instantly the drawbridge flew up, down came the portcullis,

the gates were closed and barred. Jeanne the Maid was shut

out.

A groan came from Pierre’s lips, but his sister smiled at him

bravely; as old D’Aulon shouted:

“Treachery! In God’s name, open for the Maid.”

But the gates were closed, and the drawbridge remained up.

There was a second’s interchange of looks between the brothers

and sister as the enemy with shouts of triumph closed around

them in overwhelming numbers. Only a second, but in that

brief time they took a mute farewell of each other. Man after

man of the little company was cut down or made prisoner.

D’Aulon was seized, then Jean, then Pierre, and Jeanne found

herself struggling in the midst of a multitude of Anglo-Burgundians.

One seized her wrists, while a Picard archer tore

her from the saddle by the long folds of her crimson hucque,

and in a moment they were all upon her.

“Yield your faith to me,” cried the Picard archer, who had

seized her hucque.

“I have given my faith to another than you, and I will keep

my oath,” rang the undaunted girl’s answer.

At this moment there came a wild clamour of bells from the

churches of Compiègne in a turbulent call to arms to save the

Maid. Their urgent pealing sounded too late.

Jeanne D’Arc had fought on her last field. The inspired

Maid was a prisoner.

[23] Percéval De Cagny.

[24] So spelled in the patent. A softening of the Lorraine D’Arc.

[25] These words are on the base of a statue of her that stands in the square of the

town.

[26] Monstrelet––a Burgundian Chronicler––so writes of her.

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTINUE to CHAPTER 25 Warrior Maid

Add Joan of Arc as Your Friend on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/saintjoanofarc1

|

Please Consider Shopping With One of Our Supporters!

|

|

| |